The White War: Life and Death on the Italian Front 1915-1919 (56 page)

Read The White War: Life and Death on the Italian Front 1915-1919 Online

Authors: Mark Thompson

Tags: #Europe, #World War I, #Italy, #20th century history: c 1900 to c 2000, #Military History, #European history, #War & defence operations, #General, #Military - World War I, #1914-1918, #Italy - History, #Europe - Italy, #First World War, #History - Military, #Military, #War, #History

Orlando busied himself wringing renewed British and French commitment to the Treaty of London. Statements were splashed in the press, but Washington would not be drawn; the Department of State said only that ‘Italy was entitled to the irredenta and also entitled to establish proper strategic boundaries.’ Orlando’s government explained coolly that this meant American support for its claims to the whole of the south Tyrol, Trieste, Istria and the Albanian coast. As the infantry on Grappa moved to the jump-off trenches and the gunners on the Piave waited in their pits, the government knew that the dividend of victory was still uncertain.

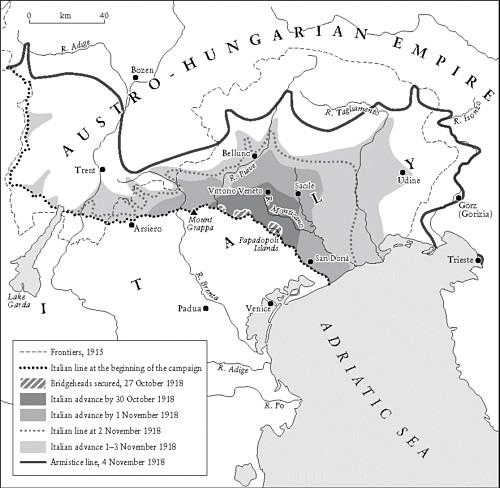

The plan of attack centred on the upper and middle Piave. Diaz would punch through the enemy lines around the road to Vittorio Veneto and Sacile, splitting Boroević’s Sixth and Fifth armies, deployed respectively on the northern and southern halves of the Piave. This would make the Austrian positions on the Asiago plateau and Mount Grappa untenable.

Of Diaz’s 57 infantry divisions and four cavalry divisions, including three British, two French and one of Czechoslovak volunteers, some 33 would be committed in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto. The spearhead would be the Eighth Army, comprising 14 divisions under General Caviglia. Its right flank would be protected by the Tenth Army: two British and two Italian divisions, under Lord Cavan. To its left, the small Twelfth Army (one French and two Italian divisions, under a French general) would secure the Piave below Mount Grappa and cross the river at the same time as the Eighth Army. Grappa itself was the responsibility of General Giardino’s Fourth Army, which had to support the Twelfth Army with counter-battery fire. The other armies in the battle, the Sixth on the Asiago plateau (six divisions, including one British and one French) and the Third on the southern portion of the front, were to await developments.

Much depended on the river. Even if the Piave behaved itself, infantry columns made easy targets, silhouetted against expanses of shingle. When Diaz drew up his operational orders on 12 October, the river was running high. Under mounting pressure to move, he made a crucial decision: the attack would start on Mount Grappa instead of the Piave. Strengthened with three extra divisions and 400 extra guns, the Fourth Army would drive the Austrians off Grappa and then thrust northwards up the valley of the River Brenta, enveloping the Austrian force on the Asiago plateau. The operation on the Piave would begin overnight, less than 24 hours after Giardino’s attack in the mountains.

The Allies started with every advantage. Apart from infantry strength, their superiority in guns and aircraft had increased since June. Boroević decided to cede ground where he must, in the hope of counter-attacking later. This was a desperate gamble; if morale was as fragile as he suspected, the second and third lines and reserves might crumble when the enemy overwhelmed the first line. But there was no alternative. On 17 October, his order of the day exhorted the army to fight for ‘an honourable peace’. Privately anticipating a catastrophe, he laid plans for an orderly retreat with mobile rearguard protection. A dynastic loyalist to the end, his priority was to preserve his forces so that they could defend the empire against its internal enemies after the armistice. And these enemies were multiplying: on the 23rd, hours before the Italians attacked, several Hungarian units refused to go up the line, and two Bosnian companies mutinied.

The Battle of Vittorio Veneto, October–November 1918

Attacking on schedule, the Fourth Army quickly ran into trouble. Giardino had less than a week to prepare an operation for which no studies existed, and the Austrian positions on Mount Grappa were strong. Boroević had expected the attack to begin on the high ground, and Italian artillery had been shelling the Austrian lines on Grappa for days, so there was no surprise. When more rain fell on the 24th, Diaz had to delay the Eighth Army’s attack – by 48 hours, as it turned out – which deprived Giardino of support on the right. Worst of all, the Italian tactics were primitive: infantry units were spread evenly, regardless of terrain, and advanced in lines. The fighting degenerated into a bloodbath, in Cadorna’s worst style. Austria’s initial resistance let Karl hope that all might not yet be lost. But he was not a fantasist; on the 26th, he informed Wilhelm that he would have to seek an armistice and a separate peace.

After six days’ hard fighting, Giardino had ‘no success’ to show for nearly 25,000 casualties: two-thirds of the Italian losses in the battle. Fortunately, operations on the Piave were going to plan after a delayed start. A British corps commander had proposed that the Papadopoli islands, a shingle archipelago south of the Montello, should be occupied before the main attack. This was done on 23 October,

2

leaving the Tenth Army well placed for the next stage. Still, the island was separated from the Austrian lines by the main channels of the river, almost a mile wide, brimming and raging after days of rain. There was little that Cavan could do but wait.

Eventually, under cover of night on the 26th, the Tenth Army moved in strength across to the islands. Norman Gladden, a private in the 11th Northumberland Fusiliers (23rd Division) who had survived the Somme and Passchendaele, was among the troops waiting on the western shore. Over his shoulder, he saw ‘thousands of gun flashes coalescing to form a continuous blaze of light along the bank’. In front, the pontoon bridge was a frightening sight.

A string of small boats had been thrown across the river in such a way that the powerful current tended to force them closer together, and they supported a planked gangway, which was roped across their gunwales. Over this bridge the assault troops had to pass, regulated by an Italian boatman to ensure that the structure should not become overloaded at any point. We were to proceed at three-pace intervals. I saw a steel-helmeted figure mount the bridge and stride slowly forward; and another, and another. The gangway stood some feet above the water and in the darkness seemed to be hung high in the air. The flaming horizon beyond threw the dark figures into relief, while shrapnel shells stabbed the darkness above.

The Austrian forward positions on the far shore were thinly manned behind the wire entanglements, and half-heartedly defended after a shattering bombardment by British gunners. A British divisional history recorded that ‘Not many Austrians stayed to fight, the majority, surprised and dismayed at the failure of the wire to hold up the attack, streamed back inland in disorder, almost too fast to give the riflemen and Lewis gunners much chance to shoot them down.’ Further north, protected by a ferocious barrage, the Eighth and Twelfth Army engineers threw 11 pontoon bridges across the river. During the night of 26–27 October, the Piave tore most of them down; Austrian artillery demolished the rest. A few Eighth Army units that had crossed the river were trapped in bridgeheads between Grappa and Montello, helpless to assist Giardino. The Twelfth Army was no better off.

In this predicament, the role of spearhead fell to the British divisions of the Tenth Army, not an outcome that has won much recognition from Italian historians. Cavan sent these divisions beyond the river at dawn on the 27th. The troops’ mood lightened as they moved eastward in the morning sunshine, meeting little resistance. ‘A new carefree attitude was taking control. We were no longer the frightened troops nailed to the earth by a storm of steel. We were advancing into enemy-held territory, victors at last.’ The Austrian 7th Infantry Division apparently panicked at the sight of the British (whose presence during the preparations had been carefully concealed), and the disarray spread to adjacent divisions. Some reserve units refused to move up when ordered.

Caviglia was stuck; high water as well as accurate Austrian shelling stopped him from enlarging his bridgehead. As had been agreed for this eventuality, he lent a reserve corps to the Tenth Army; this was sent southwards to use Cavan’s bridges. The Italian–British force crossed overnight; the northern bridgeheads of the Eighth and Twelfth Armies were linked during the 28th and extended against a patchy defence. Major Blašković’s battalion, deployed opposite a French bridgehead, was encircled and captured when a Hungarian regiment on their flank ran forward waving white rags. His men, filthy and pot-bellied with hunger, were a pitiful sight beside the smart, well-fed

poilus

.

That morning, Boroević reported to the high command that resistance by non-German troops was weakening and incidents of mutiny were increasing. ‘He was informed that the government had asked President Wilson for an Armistice, and commented that this news would hardly raise morale.’ Diaz’s original plan was taking shape: the Allies were moving towards Vittorio Veneto and Sacile, the axis that should split the Austrians. To protect his Sixth Army, Boroević ordered four reserve divisions to prepare to engage the enemy. One division refused to budge; the other three took up positions on a stream called the Monticano, between the Piave and the Livenza. He also feared the envelopment of the Fifth Army, which had not been tested because the Duke of Aosta’s men were still on the right bank, though crossings were now imminent. So he ordered the Fifth to withdraw to the Monticano line. Here the empire made its last stand.

Late in the day, Lord Cavan ordered his divisions across the Monticano. Except for an Italian battery, the British lacked artillery support; it took the whole of 29 October to knock out Austrian machine guns above the steep riverbank and in isolated farms. The issue was settled by nightfall, and Boroević ordered a retreat to the River Livenza, a few kilometres further east. He had urged the high command to tell the Italians that Habsburg forces would pull back behind the 1866 border, unilaterally evacuating the Veneto. (Preparations for this contingency had been in hand since 14 October, when the high command ordered the armies in Italy to send all inessential equipment and infrastructure to the interior of the empire.) General Arz, conceding that the army in Italy was finished, ordered Boroević to withdraw at once, as a token of goodwill. Cavan’s forward units saw the sky light up as the Austrians burned their ammunition dumps. In Austrian accounts the retreat was dreadful but not headlong; ‘a semblance of order’ was ‘maintained by sheer force of habit, a march into nothingness’.

Back on the Piave, the bridgeheads were enlarged all along the river. The final stage of the battle began on the 30th, with Italians pouring across the river in strength. Allied heavy guns crossed as well, which cheered the advance units, though resistance faded so quickly that artillery support was superfluous. Civilians emerged from their cottages, their faces taut with starvation, to cheer the Allies. In the morning, cyclists and bersaglieri of the Eighth Army occupied Vittorio Veneto, some 16 kilometres beyond the Piave. Later that day, forward units reached the River Livenza.

As per Diaz’s plan, divisions of the Eighth and Twelfth Armies swung northwards, forcing the Austrians to withdraw from the Grappa massif or be encircled. The manoeuvre succeeded; with the Fourth Army advancing at last, the Austrian Eleventh Army was exposed on the Asiago plateau. That night, it withdrew from front-line positions. The Sixth Army turned this tactical retreat into a rout. Over the next three days, the British 48th Division took more than 20,000 prisoners for the loss of 26 killed and 129 wounded.

Let us pick up the story of Jan Triska, the Czech artillery officer, who returned from home leave in mid-September. On 30 October, with the Italians less than 10 kilometres away, Jan’s regiment prepared to retreat. For the first time ever, the men were ordered to fall in, in national groups. A second shock followed: the officers canvassed views on the future of the empire. Who was for the Emperor? Sixty hands went up. Who was for a republic? Eighty-six hands. And who wanted a national state of their own? Some forty Czechs raised their hands.

On the last day of October, the Italian line moved steadily eastwards. Cavan’s 23rd Division liberated Sacile. Austrian rearguards tried to delay the Allies as huge numbers of soldiers made for the River Tagliamento, abandoning everything, burning the bridges as they went. Writing to his wife, Diaz allowed himself, for once, to exult. It was, he said, ‘Caporetto in reverse’. Victory was assured. ‘I have won the war more by the strength of my heart and nerves than by any intellectual gifts, and I feel stronger, more balanced, than all of them’ – meaning the politicians who had carped at his caution.

A woman on the road from Conegliano to Vittorio Veneto was seen shouting triumphantly ‘Now it’s goodbye, Caporetto, and good riddance!’ Across the empire, nations emerged or re-emerged into history. Karl refused on principle to approve the use of force against the separatists.

The Italians were in no hurry to reach an armistice, and Karl’s negotiators were not received at Padua until the 31st. General Badoglio treated his opposite number, General Viktor Weber von Webenau, with cold formality. That morning, representatives of the American, British, French and Italian governments – the ‘Big Four’ – had met in Paris to discuss armistices with Germany and Austria. They agreed that the Italians, acting on behalf of the Allies, should occupy Habsburg territory along the eastern Adriatic, according to the Treaty of London. Some good historians have accused Italy’s partners of missing a crucial opportunity; instead of handing the Italians control over the territory pledged in the Treaty of London, they should have raised the Treaty’s incompatibility with Wilson’s principles. It is an unhistorical objection, for the Central Powers were still undefeated and the Allies were still bound by the Treaty, which Wilson himself would not dispute before a full-dress peace conference. It may be that Wilson’s envoy in Paris, Colonel House, ‘knew literally nothing about the Adriatic and cared even less’, in the bitter judgement of one of these historians; this does not mean his decisions on the last day of October were wrong or cynical.

While the talks continued in Paris and Padua, the Allies attacked the rearguards and retreating columns. The road from Sacile to Pordenone was packed with Austrian troops ‘in headlong retreat … bombarded, bombed and machine-gunned from the air’. The future Marxist critic Ernst Fischer, commanding a half-battery of howitzers on the Piave, observed the Allied planes strafing the highway with a sharp eye: ‘Under the impact of the hail of metal the road puckered like the skin of a freezing man.’ They were freezing, too, unable to sleep for cold. Next day, Lieutenant Hugh Dalton of the Royal Artillery – who would serve as chancellor of the exchequer in the great reforming Labour government after the Second World War – saw the ditches full of dead men and horses. ‘The loss in wrecked and abandoned material of every kind had been immense.’ People were already eating the dead horses.

Elsewhere, the last Habsburg governor of Trieste received a cable from Vienna at 19:30 on the 31st, announcing that Austrian rule on the Adriatic Sea was over. He left by train the following day, shortly before Diaz ordered a general advance along the whole length of the front.

3

By 2 November, the Asiago plateau was completely in Italian hands. Advance units crossed the Tagliamento in the afternoon. Several Tyrolean regiments – the last Habsburg units still fighting – surrendered. Boroević telephoned the high command: as it had become impossible to ‘defend our borders’, what should he do? He was ordered to move as many intact units as possible to the hinterland so they could be transferred to their new national states.

At the Villa Giusti, Badoglio handed over Italy’s terms for an armistice. The Austro-Hungarians must stop fighting at once; the imperial army must be reduced to 20 divisions and surrender half its artillery; all the occupied territories (corresponding to the Treaty of London) must be evacuated within a period to be decided by the Allies; all German troops must leave the empire within 15 days; all Allied prisoners of war must be liberated at once; and the Allies must have free use of all imperial transport networks. The terms were nonnegotiable and the Austrians had until midnight on 3 November to accept.

In the echoing halls of the Schönbrunn palace, Karl conferred late into the night with his prime minister, foreign minister, and chief of staff. He was especially troubled by the prospect that the Allies would use their freedom of movement to attack Germany from imperial territory – an eventuality he had promised to forestall. Arz advised him to accept as the only way to save hundreds of thousands of lives. This was an appeal he could not resist, but he still wanted his government’s approval. Some form of assent was obtained, and the commanders at the front were informed; rashly, they were ordered to cease hostilities at once. At this point, early on 3 November, the high command was unaware of an Italian stipulation that the ceasefire should come into effect with a 24-hour delay, so their forward units could be informed. General Weber realised the discrepancy would be disastrous for Austrian troops, but the high command refused to amend the order. In desperation, Weber asked Badoglio to suspend hostilities immediately. His request was brushed aside, and the Italians signed the armistice at 15:20. It would come into force at 15:00 on 4 November.