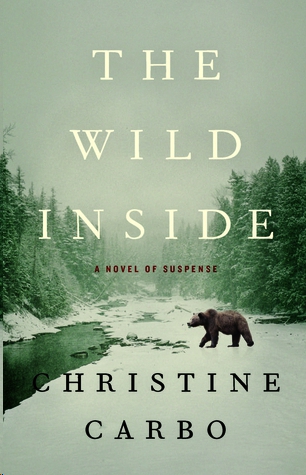

The Wild Inside

Thank you for downloading this Atria eBook.

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to bonus content, and info on the latest new releases and other great eBooks from Atria and Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

For my mother, Françoise (Jeanine) Schimpff,

and my father, Robert Schimpff

Every death even the cruelest death

drowns in the total indifference of Nature

Nature herself would watch unmoved

if we destroyed the entire human race

I hate Nature

this passionless spectator this unbreakable iceberg-face

that can bear everything

this goads us to greater and greater acts . . .

—PETER WEISS,

The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat . . .

Fall 1987

P

ALENESS SLIPPED INTO

the dark sky and erased the stars as gracefully and peacefully as if nothing had happened. I struggled for breath, my chest shuddering violently each time I pulled in the bitter air. My teeth clattered noisily, and I couldn’t feel my legs. I knew my jeans had been wet earlier, and they were frozen and hard as cement now that the fire had faded.

I continued to stare in the direction he’d been dragged. All the noises had ceased except the sound of the gusting wind and the water lapping on the shore. But all the others—the screams, the grunts, the scuffling sound of the underbrush . . . Even the small animals I’d heard scampering for cover . . . had not resumed their activity. And the fire—its crackles and pops had stilled as it died to a pile of white ashes with small embers. I couldn’t remember starting it. Couldn’t remember feeding it and keeping it stoked. A gust of cold wind slapped the smoldering smoke into my face. I flinched and tried to stand, my numb legs not wanting to work. I clenched a long stick and stared at it as if my arm had morphed into an alien appendage.

I quickly looked back to the opening in the brush that I’d been watching for several hours, even when the light was syrupy dark and I’d waited for amber eyes to come for me. The branches of bushes and small, stunted spruce were broken, the skunkweed and bear grass flat

tened and smeared with a trail of blood. I squeezed my eyes shut and pictured my ma and my sisters at home in their warm beds. I ached for my mom, for her arms around me. Then I heard the screaming again in my head. Right between my ears, expanding and pushing against my skull. I started to run, first stumbling, then full force. I ran and ran, faltering and tumbling over the hard, lumpy ground, over the edges of buried rocks and exposed roots on the well-maintained trail. I ran until it all went black.

1

Fall 2010

I

F I COULD

reveal one particular thing about my way of thinking it would be this: I was a fourteen-year-old boy when that feral, panic-filled night ruined my ability to see the glass as half full. It’s still hard to talk about, but in terms of self-definition, nothing comes close to that crucial three-hour span of hellish time when the emotional freedom that comes from trusting the foundation one stands on would wither like a late-fall leaf. Up until then, my mom, Mary Systead, with her hazel eyes and dimples, a hospital pharmacist and a lover of self-help and pop-psychology books, had always ridden me about being a positive thinker, telling me that I had a bad habit of seeing the glass as half empty and that if I didn’t learn to overcome it, it would have a bad effect on my life. At the time, I had no idea what she was talking about. And later, I couldn’t imagine what could be more negative than what ended up happening: losing my dad and lying in the hospital for weeks like a heavy bag of sand, listening to the orderlies telling me how lucky I was not to have died.

But that desolate late-summer night all those years ago at Oldman Lake, the stuff of great sensationalism and freaky campfire stories, isn’t what’s interesting to me now. What

is

notable is my knack for glimpsing the dark intersection of good and evil in people and seeing how it can be traced back to that fateful period. Because, although this can be taken as positive thinking itself—and I’ll admit that traces of it creep

in—my critical nature has made me fairly decent at what I do, which is working as a special agent—we call it Series Eighteen-Eleven—for the Department of the Interior’s National Park Service.

Most people think of me as a glorified ranger because nobody ever imagines that crime occurs in the nation’s parks. But it does: drug manufacturing, cultivation and trafficking, illegal game trading, theft, arson, archeological vandalism, senseless violence, and, of course, homicide. Not to mention that the woods happen to be a great place to dump bodies. The United States has fifty-eight national parks with about eighty million acres of unpaved, unpopulated land. I and two guys from the department are trained to undertake homicide investigations and are stationed in the western region, which means our offices are in Denver so that we can cover numerous sites: Yosemite, Yellowstone, the Grand Tetons, Bryce Canyon, Glacier, Joshua Tree, Mesa Verde, Death Valley, the Great Sand Dunes, the Olympic Peninsula. . . .

Mostly, we work solo on cases, even homicides, since we have so much help from Park Police—they’re Series Double-O-Eight-Three. Sometimes, being assisted by Park Police is helpful, but sometimes it’s a pain in the ass since we’re not in the habit of working together and we often clash in the way we go about the little things. It’s the nuances, like knowing when to stay quiet, when to offer a small compliment, when to put on the unimpressed, bored look or to take the lead or to follow.

The other thing that can be traced to that night is my obsession with the grizzly.

Ursus arctos horribilis

. The grizzly was listed in 1975 as a threatened species in the lower forty-eight after being trapped and hunted to near extermination in the last century. One would think I’d be terrified of them, and here’s the deal: I am. In fact, I became a policeman after college, because even though I double-majored in criminology and forestry, I felt this fairly significant panic at the base of my sternum at the thought of being alone in the woods.

There’s a catch for me, though: when I read or know about one of

them getting shot by a hunter (always accidentally they claim) or getting euthanized for becoming too dependent on human garbage, I’m conflicted. I can’t tell if I’m pleased, sad, or pissed off. It’s as if each time one of these specimens, with their scooped, broad noses, cinnamon and silver-tipped coarse hair, eyes like amethysts, and the infamous hump protruding like a warning, is killed, either another piece of my father dies with them or he is given a small slice of justice. Over the years, I’ve become more and more intrigued, as if they’ve taken on some godly status. I’ve studied them from afar—reading everything I could get my hands on: mostly journals and published graduate theses on behavior, habitat use, and demography. After all, knowledge is power, and power helps alleviate fear.

So one could say that for a detective-slash-quasi-grizzly aficionado, I was heading into a perfect storm with this next case. And I could say this about the case as well: my torn recipe for positive thinking, with its already unpatchable shreds, would turn to jagged teeth, biting me even deeper than I thought possible.

2

T

HE WAY I

see it, negative thinking can have positive outcomes. Take my habit of rolling a quarter across my fingers, just under the knuckles where you teach kids how to track the number of days in the months. I’m a lefty, so I can only do it on that hand. When I was about fifteen I saw a guy rolling one behind the checkout desk at the County Library where my sisters and I would go after school until Ma finished work. I figured that since you could even get attached to the inanimate, to a particular object, you stood to lose that object. And even if careful, you could still misplace it, like when I lost the one-inch-long shark tooth I had found in the woods behind our house in Florida. I had religiously carried it with me everywhere for good luck.

But a habit or a behavior was different; you couldn’t lose a habit, not one that you intended to keep. It could stay with you for the rest of your life if you chose it. So instead of getting attached to

a

particular quarter, like the 1964 all-silver quarter my father gave me when I was ten, if I could learn how to roll one instead, it would be the action I loved, not the object. If I lost the coin, it could always be replaced.

So rolling a quarter (this one happened to be a Vermont, with a man collecting sap from two maple trees) on a late-October early morning in our department offices in Denver is exactly how Jeff LaMatto found me. The coin’s new shininess flickered as it flipped and slid down and out of each crevasse between my fingers, hid under my palm, then reappeared by my thumb to begin its journey again. My

coffee mug was full and the

Denver Post

spread before me. Being a Saturday, we were only teed up to work until noon.

“Well, Teddy boy.” LaMatto caught me off guard and almost made me drop the damn quarter. “Looks like you’re heading out in an hour and a half to your hometown. Better pack your undies.” He threw the file he was holding onto the side of his desk. “Lucky me. I get to stay here on the Thompson case.”

“What’s happened?” I resumed my rolling.

“Didn’t get the details, but it sounds like it might be a strange one. Boss definitely wants you ’cause of your expert

ise

.” He hissed the

s

on the last syllable.

“Expertise?”

“Your neck of the woods, right?” Jeff knew that Kalispell, Montana, was where I went to high school and worked after college for the local police force for three years after getting my degrees at the University of Montana in Missoula. Three whole distressing years of feeling like I was going to suffocate in the town that my family moved to so my parents could find their mountain paradise: forty minutes from Glacier Park, twenty to the nearest ski resort, and fifteen to Flathead Lake, the largest natural freshwater lake west of the Mississippi. By that third year, in spite of the “big sky” and the open fields, everything felt too close: the streets, grocery stores, movie theaters, schools, barns, trees, and alfalfa and hay fields. Every time I’d get in my unit vehicle to work, I felt like I couldn’t sit still and that my skin wanted to itch. Each pothole I’d hit on the shabby roads made my jaw clench. Each time I’d have to pull over to drag a bloated and bloody dead deer off a city road, I got more and more irritated. I shouldn’t even mention the shotgun marriage to Shelly, the miscarriage, and our divorce eighteen months later.

I knew I had to get out, so I applied to the DOI Special Agent Series Eighteen-Eleven. I was perfect for the position because of my officer training and my dual degrees. After getting in, I did about fifteen

months as a background analyst, another eighteen in trafficking, then worked my way into homicide. “Somebody dump a body in Glacier?” I asked.

“Not sure. Said something about a griz.”

“Oh.” I stopped rolling and wrapped my hand around the coin. I felt that tiny clench, like a small imaginary fist gripping right above my stomach. Nothing that surprised me; I’ve learned to live with it, like a person with an ulcer endures the knife twist of pain up high in their gut. “Has one fed on a carcass?” I pressed the serrated edge of the quarter into the point of my chin.

He shrugged. “Not sure. He was vague, but that’s my guess. Said there’d been a mauling.”

“A mauling?” I felt like I was being toyed with and eyed Jeff. His close-cropped strawberry-blond hair picked up the first strokes of dawn fingering through the large windows by our desks. A coworker and sometimes partner on more severe cases, Jeff loved to be secretive, feeding bits and pieces at a time like I was a dog begging for a biscuit. Plus he thought he was funny, like when he imitated Arnold Schwarzenegger or John Wayne. There’s nothing more irritating than having to dredge up a fake smile or laugh for a partner. For a witness, no problem, for a partner, big problem.

“I guess you could call it that.” He punched some keys on his cell, talking to me with the distant interest of a parent trying to complete a task while a child asks too many questions.

“What do you mean—you could

call

it that?” Feeding on a stiff is far different from a mauling, and if it was a mauling, it didn’t have anything to do with us. The rangers handle maulings; we handle crime. “Either a bear attacks or it doesn’t. They find drugs on the body?”

“Don’t know.” Jeff held his cell to his ear and stacked some files neatly to the side with his free hand. He’d been acting particularly superior for the past month and a half because he had solved a case in the Tetons involving a hitchhiker who went missing. If you asked me,

he’d gotten lucky, getting a dead-on clue from a tourist who came forward with a picture he happened to take showing the missing guy right next to the Jenny Lake trailhead sign. What are the chances? When I mentioned it to Jeff, he gave me some tight-assed comment about luck being where “opportunity and preparation intersect.”