Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (46 page)

Most important, Roosevelt believed that westerners would have to become good wildlife protectionists themselves in order for buffalo herds, national parks, and forest reserves to remain unmolested. Regular citizens would have to turn in poachers, even if the poachers were friends or neighbors. Emerson used to quote Francis Bacon as saying that humans were the ministers and interpreters of nature; Roosevelt wanted to add a modern point: and

protectors

. Somehow, Roosevelt believed, the people of the West needed to adopt the buffalo permanently as their mascot. “Eastern people, and especially Eastern sportsmen, need to keep steadily in mind the fact that the westerners who live in the neighborhood of the forest preserves are the men who, in the last resort, will determine whether or not those preserves are to be permanent,” he wrote. “They cannot…be kept…as game reservations unless the settlers roundabout believe in them and heartily support them.”

79

IV

A shock wave rippled through Roosevelt’s life on August 14, 1894, when news reached him that his brother Elliott had died. The

New York Times

cited heart disease as the cause of death, but Theodore knew it was heartbreak. Elliott’s wife, Anna, and son, Elliott Jr., had died of diphtheria in the preceding years. Unable to ward off the demons of the double loss, Elliott had been drinking heavily all summer long. Theodore felt downcast, but found a bit of closure at the funeral. “When dead the poor fellow looked very peaceful,” he wrote to his sister Bamie, “and so like his old, generous, gallant self of fifteen years ago. The horror, and the terrible mixture of sadness and grotesque, grim evil continued to the very end; and the dreadful flashes of his old sweetness, which made it all even more hopeless.”

80

Elliott left behind his ten-year-old daughter, Eleanor, who was then raised by her grandmother Mary Livingston Ludlow Hall.

No sooner was his brother buried than Theodore headed to North Dakota for a couple of recuperative weeks. Once again he left his wife and children behind. With Bill Merrifield accompanying him, Roosevelt went antelope hunting on the plains around Medora in honor of Elliott. Game

was scarce that year, chased away by Plains Indians and Dakota sheepherders. Nevertheless, he managed to shoot, skin, and eat five antelope. Drinking in a bit of Badlands solitude helped bring perspective back into his life. Full of deep thoughts, he spent his nights sleeping in his buffalo-lined bag in the open grassy plains with a tarpaulin to pull over him if the wind squalled. As if following the stations of the cross, he visited the great landmarks of the North Dakota Badlands—Sentinel Butte, Square Butte, and Middle Butte. “Great flocks of sandhill cranes passed overhead from time to time,” Roosevelt wrote, “the air resounding with their strange, musical, guttural clangor.”

81

The deep-rooted sagebrush of the plains colored long stretches of the parched summer landscape. “The cattle aren’t doing particularly well,” Roosevelt told Lodge in a letter. “The drought has been very severe on everything. However, except for feeling a little blue, I passed a delightful fortnight all the time in the open; and feel as rugged as a bull-moose.”

82

The year 1894 also saw the publication of Volume 3 of

The Winning of the West

, covering the post–Revolutionary War expansion into the Ohio River Valley, the Tennessee Valley, and the Blue Ridge Mountains of Kentucky. The book is marred by stereotypes of Indians as being “cunning and stealthy,” essentially “the tigers of the human race.” Roosevelt claimed it was only natural that white Americans would persevere. “The rude, fierce settler who drives the savage from the land lays all civilized mankind under a debt to him,” he wrote. “American and Indian, Boer and Zulu, Cossack and Tartan, New Zealander and Maori—in each case the victor, horrible though many of his deeds are, has laid deep the foundations for the future greatness of a mighty people.”

83

Such passages, redolent of the white man’s burden, occur throughout Volume 3 of

The Winning of the West

—Roosevelt even promotes his theory of “dominant world races” over “aboriginals.” In his landmark study

Theodore Roosevelt and Six Friends of the Indian

, the historian William T. Hagan was generally perplexed at the difference in attitude toward Native Americans in Volume 3 of

The Winning of the West

compared with Roosevelt’s humane reports of 1894–1895 as civil service commissioner. Influenced by Indian rights activists among his friends—especially Charles L. Lummis, Herbert Walsh, George Bird Grinnell, Hamlin Garland, C. Hart Merriam, and Francis Leupp—Commissioner Roosevelt (unlike the historian Roosevelt) said that the defeated Indians deserved a “square deal” from the U.S. government. These stark differences within Roosevelt, reminiscent of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, would have caused Robert Louis Stevenson himself to scratch his head in puzzlement. Roosevelt number one (of

The Winning of the West

) seemed to loathe Indians. Roosevelt number two (of the civil service reports) fought for their human rights.

The rational explanation lies in Roosevelt’s belief that it was only proper to treat a defeated people with dignity. A true nineteenth-century gentleman, he put his faith in the hope that education, assimilation, and the example of white Americans would improve Native Americans’ lot in the near future. In fact, he envisioned the day when high-quality men like Luther Standing Bear and Few Trails would dine in the White House. Regardless of which side was the

real

Roosevelt, his ideas intersected in a singular way: he

consistently

saw the Indians’ future in North America in stark Darwinian terms. Once U.S. federal government graft, skimming, and unconstitutional injustice were removed from the reservations, Roosevelt argued, it would be up to individual Indian tribes to survive. He had high hopes for the Cherokee and Pawnee, less so for the Sioux. “We must turn them loose,” Roosevelt wrote in one report, “hardening our hearts to the fact that many will sink, exactly as many will swim.”

84

T

HE

B

RONX

Z

OO

F

OUNDER

I

I

n the autumn of 1894, Roosevelt began collaborating with Madison Grant, a lawyer and explorer, on the creation of the New York Zoological Society. With his waxed handlebar mustache, Yale pride, penchant for bow-ties, and habit of always talking with his hands clasped as if in prayer, Grant was a preeminent figure in the world of zoology, credited with discovering several North American subspecies of mammals (a species of Alaska caribou was named

Bangifer granti

in his honor).

1

That very year he had written for

Century

an article entitled “The Vanishing Moose,” which Roosevelt loved.

2

Now both wildlife protectionists would turn their attention to the vanishing buffalo as part of their ambitious scheme for a new American zoo.

3

This zoo would be situated in the Bronx, then a rural section of New York City. Roosevelt and Grant had been disappointed by the European zoos they visited. Little educational information was disseminated to visitors about species variation or habitat, and most zoological parks emphasized the freakishness and oddity of their collections. Such come-ons as a six-legged deer in Berlin and a two-headed turtle in London sickened Roosevelt. Worse yet, the animals in European zoos paced back and forth in tiny cages, like prisoners waiting for the end of a lifetime sentence. This kind of backward zookeeping had to end. As Roosevelt envisioned it, their modern New York zoo would be built “on lines entirely divergent from the Old World zoological gardens.”

4

The animals would have more room, in open-air exhibits where possible, and broadsheets would be created specifically for schoolchildren explaining the principles behind wildlife preservation and Darwinian evolution. And while the Bronx Zoo wasn’t as showy as a production by P. T. Barnum or Buffalo Bill, the Chicago Exposition had taught Roosevelt to think outside the box when it came to devising a tourist attraction that would bring throngs to see wildlife up close. A subway stop, in fact, was slated to open at the southeastern entrance to the zoological park.

In planning this zoo, Roosevelt and Grant included a singularly ambitious goal: they would breed buffalo in captivity there and eventually would turn them loose throughout the Great Plains and upper Rocky Mountain region. This so-called New York repopulation plan would rein

troduce buffalo in their traditional grounds, such as the Black Hills, Pine Ridge Reservation, Flint Hills, Osage Hills, and Wichita Mountains; even the remaining herd in Yellowstone Park would be augmented with Bronx-bred buffalo. As Roosevelt saw it, buffalo would once again be trampling the luxuriant tall grasses into muddy thoroughfares, as in the days before Christopher Columbus. Unlike the 45 million cattle in the Great Plains, reinroduced buffalo wouldn’t overgraze the prairie into a dust bowl. He hoped to create a buffalo common. While there were few dramas as frightening as a bison bull at bay, zoologically schooled members of the Boone and Crockett Club like Roosevelt and Grant nevertheless knew that buffaloes were essentially timid creatures, as easy to corral as cattle. Only when a mother buffalo felt that her young were in jeopardy did they turn frothingly hostile, staving off predators such as wolves and cougars with the threat of a horrific stampede. Then look out! Buffalo might appear slow and lumbering, but they could outrun a racehorse. As domesticated creatures, however, they were fairly benign.

5

While George Bird Grinnell was supportive of a Buffalo common in the West, he thought bison needed lots of roving space to survive and that the New York grasses were completely different from those on the plains. Therefore, he wasn’t keen on the Boone and Crockett Club’s throwing its weight behind acquiring wildlife for display in New York City; he preferred having the members concentrate on enacting tougher hunting laws. Running a zoo was a headache he simply didn’t want. To Grinnell it made more practical sense to have the Department of Agriculture help

C. J. Jones of Garden City, Kansas—who had captured fifty buffalo on his own and purchased an additional eighty in Manitoba—lead a serious repopulation program right in the heartland of “Buffalo Country.”

6

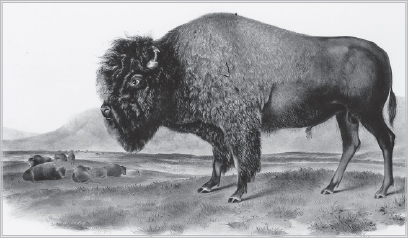

The Great American Buffalo

was drawn by Audubo

The Great American Buffalo. (Courtesy of the Boone and Crockett Club)

But, as was often the case, Roosevelt got his way. He insisted that the zoo would teach New Yorkers about the perils western big-game species faced. Also, the zoo allowed Roosevelt, as a New York politician, to found something great for the Empire State, an added political bonus. One of the zoo’s most tireless advocates, in fact, was Andrew H. Green, then known as the “father” of greater New York City. When Green concurred that a natural-setting zoo was a fine idea, long overdue, Roosevelt knew his brainchild would take off. A truly creative philanthropist, Green had been a close friend of Roosevelt’s father, envisioned Central Park as a recreational center, bankrolled the American Museum of Natural History, investigated the Tweed Ring, and created the Niagara Falls Commission to save the falls from destruction in a bilateral agreement with the Canadian government. Grinnell warned his friends against forming a zoo committee in late 1894 before club members could, at the very least, vote on the idea. They should settle their differences, Grinnell believed, through at least a tip of the hat toward the democratic process.

But Roosevelt, spurred by his idea about buffalo, had another important ally besides Green and Grant. Professor Fairfield Osborn of Columbia University, curator of the American Museum of Natural History, sided with Roosevelt (as he always did), even offering his fund-raising contact list. Starting in the 1890s Osborn had become quite a fixture in zoological circles. The refined, fashionable Osborn would tuck a paisley scarf into his collar instead of a tie, sported corduroy pants, and was constantly jotting notes on legal pads while chain-smoking cigarettes. Green was the first president of the New York Zoological Society, but when he became suddenly ill Osborn took over the obligations. Deep down, Roosevelt probably knew that Grinnell was correct in his skepticism. Roosevelt nevertheless wrote to Madison Grant—whose hand-tailored suits and donnish manners made him a kind of WASP caricature, like a cucumber sandwich at afternoon tea—that regardless of

Forest and Stream’

s view-point, “I’ll go ahead and do it.”

7

Being the impresario of a zoo was simply too irresistible to turn down.

In the spring of 1895, a group from the Boone and Crockett Club officially formed the New York Zoological Society. The leaders included Roosevelt, Grant, Green, and Osborn. Behaving like fraternity brothers, they created a crest for the society, with a ram’s head in its center and “Founded 1895” underneath, long before the development plan was of

ficially approved in late 1897.

8

The 261-acre forested zoo, with a topographical range from granite ridges to natural meadows and glades to forest, was ideal for a wide variety of animals to thrive in the open air. The Bronx River wound through the site, and the woods were already home to many birds. It would be relatively easy to create marvelous replicas of diverse habitats here, allowing the wildlife to feel at home.

The zoo officially opened in November 1898, after the blitzkrieg of the Spanish-American War. Grinnell essentially fell into line, now and again flashing an over-the-shoulder look that said “I told you so” when any animal emergency transpired; Darwianism, he believed, was veterinarianism. Roosevelt was especially proud of the imposing Antelope House. But the Lion House soon became the premier tourist attraction. These “houses” were established to tell the biological history of species in a truly detailed, exciting, educational way. A special wooded range had been developed for moose, and a wonderful stream surrounded by plants was devised so children could watch industrious beavers construct dams and lodges. At the time, the new zoological park was the largest in the world, and its open-air displays became the model for its successors, such as the zoo in San Diego, which opened in 1922.

As it entertained tourists and educated schoolchildren, the zoo simultaneously served as a scientific laboratory. For example, the twenty acres reserved for buffalo allowed ample space for mammalogists to study these North American quadrupeds through the rutting cycle.

9

Likewise, elk got fifteen acres in which to thrive and be observed. Moose were brought in from Maine and cougar from somewhere west of Kansas City. Aesthetically, what Roosevelt and Grant were trying to avoid was the zoo seeming like an oversized breeding pen. Bear dens were soon erected with awesome caves and rock precipices, and there were plans to build the world’s greatest House of Reptiles, which the foremost herpetologist in America, Raymond L. Ditmars, would curate. “It is extremely desirable that all animals living in the open air should be so installed that their surroundings will suggest,” the

New York Times

explained about the new zoo, “as a well-kept and accessible natural wilderness rather than as a conventional city park.”

10

Besides breeding buffalo in captivity, the New York Zoological Society funded an extensive scientific report on the concept of creating wildlife sanctuaries or refuges across the country. Could buffalo reclaim the Black Hills, Red River Valley, or Drift Prairie of South Dakota? Would elk be able to roam freely again along the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers? Someday, would moose be protected in Maine and Minnesota? As Lincoln Lang

recalled in

Ranching with Roosevelt

, T.R. “had discussed the possibilities of game protection,” in the 1880s and even spoke of someday establishing the North Dakota Badlands as a “national preserve.”

11

With the zoological society launched, Roosevelt’s vision was no longer an impossible goal. A subtle brotherhood of men—hunters and naturalists—were now in the business of species education.

Already at Black Mesa Forest Reserve in the Arizona Territory two members of the Boone and Crockett Club—Dr. Ed W. Nelson and Alden Sampon—were studying the feasibility of a wildlife reserve in the Navajo lands, a reserve that would be completely off-limits to hunters along the upper border of the Little Colorado River basin.

12

The deep box canyons, yellow pine forests, piñons, cedars, and junipers of the Black Mesa needed protection, as did the three intact cliff dwellings of the Pueblos. Although Roosevelt hadn’t been to Black Mesa, he knew from Nelson that creating a big-game reserve there would be ideal for black-tailed deer and silver-tipped bears. And it would mean a great deal to the Native American peoples. But Roosevelt also understood that without irrigation the Arizona rock oasis would become uninhabitable; the scattered pines would wither. The residents of the adjoining sheep and cattle settlements were opposed to a Black Mesa wildlife playground.

13

Roosevelt—unusually for him—made snide, belittling remarks about the Arizona business types who were unable to comprehend the concept of antiquities. Arizona needed to be maintained, not mined. Stopping growth in Black Mesa, Roosevelt worried, was going to be difficult, but he believed the “fantastic barrenness,” “incredible wildness,” and “desolate majesty” of the Navajo lands needed to be protected forever. With quiet cheerfulness he began looking for ways to get the job done. “No one could paint or describe it,” he later wrote after camping out in the Black Mesa valley, “save one of the great masters of imaginative art or literature—a Turner or Browning or Poe.”

14

II

The recruitment of William Temple Hornaday as the first director and general curator of the New York Zoological Society was a brilliant coup by Roosevelt. (Like George Bird Grinnell, Hornaday regularly used all three of his names.) Born in Plainfield, Indiana, in 1854, four years before Roosevelt, and raised in Iowa starting in 1856, Hornaday grew up earthy and dirt-poor.

15

“I shall always believe,” he wrote in his memoir

Two Years in the Jungle

, “I was born under a lucky star as a compensation for not having been born rich.”

16

He managed to attend Oskaloosa College and

then Iowa State College, where his intuitive genius for handling both domestic and wild animals, added to his excellence in taxidermy, opened the doors to a zoological career upon graduation. While Roosevelt was preparing for Harvard with a private tutor, the irascible Hornaday was traveling the world as a young man searching for exotic species to shoot and stuff in the name of science. His primary employer, the Wards National Science Foundation (of Rochester, New York), sent him to the Bahamas, Cuba, Florida, Brazil, Ceylon, Malaysia, and Borneo.

Obsessive, unbuckling, and stubborn beyond words, Hornaday was a highly sophisticated version of Bill Sewall or Moses Sawyer. Unlike Baird or Merriam, Hornaday had calloused hands. There was always a mischievous twinkle in his eyes, like a child who had suddenly aged overnight. He was the kind of immature prankster who yodeled in church just to hear the echo. There was a cultivated crudeness to his manners, and his certainty about zoology bordered on arrogance. His daily conversation was filled with such bio-trivia as the flesh preferences of wolverines and why hawks were copper-clawed. Hornaday also bristled with statistics on the possible extinction of Delaware swans, Louisiana woodpeckers, and Ohio turtledoves. Vermont was the only state, he believed, which managed its wildlife properly. For all his eccentricities, you had to give Hornaday credit: he walked the walk. Unlike most Harvard-trained scientists, Hornaday had actually wallowed in the mud with alligators, tying their mouths with rope like Jim Bowie working the tip jar in a French Quarter sideshow. And when it came to buffalo, nobody—not even Grinnell—understood their psychology as keenly as Hornaday. The West was full of horse whisperers, but Hornaday—with the notable exception of C. J. Jones—was the only buffalo whisperer around. (Unlike Jones, Hornaday at least didn’t try to crossbreed wild buffalo with Hereford cattle.)