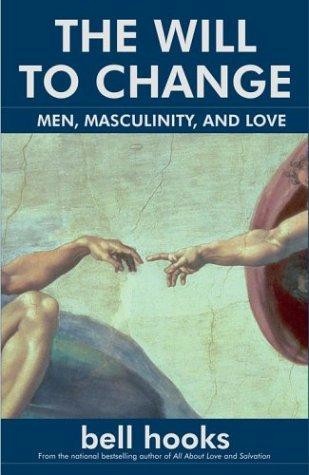

The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love

Read The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love Online

Authors: Bell Hooks

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Anthropology, #Cultural, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Social Sciences, #Gender Studies, #Men, #Women's Studies

Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism

Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center

Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black

Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics

Breaking Bread: Insurgent Black Intellectual Life

Black Looks: Race and Representation

Sisters of the Yam: Black Women and Self-Recovery

Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom

Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations

Art on My Mind: Visual Politics

Killing Rage: Ending Racism

Reel to Real: Race, Sex, and Class at the Movies

Bone Black: Memories of Girlhood, Vol. 1

Wounds of Passion: A Writing Life

Remembered Rapture: The Writer at Work

Happy to Be Nappy

All about Love: New Visions

Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center

Where We Stand: Class Matters

Salvation: Black People and Love

Communion: The Female Search for Love

Rock My Soul: Black People and Self-Esteem

1230 Avenue of the Americas

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Copyright © 2004 by Gloria Watkins

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Atria Books, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

ISBN-10: 0-7434-8033-3

ISBN-13: 978-0-7434-8033-8

First Atria Books hardcover edition January 2004

ATRIA

BOOKS is a trademark of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com

“Alchemically transforming lead into true gold, men are given the opportunity to burn, to be touched by an inner fire, to live a life of substance, to be changed utterly.”

This book is dedicated to the memory of my grandfather, Gus Oldham—burning, a heart on fire, whose love, stronger than death, illuminates.

In our rapidly changing society we can count on only two things that will never change. What will never change is the will to change and the fear of change. It is the will to change that motivates us to seek help. It is the fear of change that motivates us to resist the very help we seek.

—Harriet Lerner,

The Dance of Intimacy

About Men

W

hen Phyllis Chesler’s book

About Men

was first published more than ten years ago, I was excited. At last, I thought then, a feminist thinker will explain this mystery—men. Back then I had never shared with anyone the feelings I had about men. I had not been able to confess that not only did I not understand men, I feared them. Chesler, with her usual “take no prisoners” daring, I was certain, would not simply name this fear, explain it, she would do much more: she would make men real to me. Men would become people I could talk to, work with, love. Her book was disappointing. Filled with quotes from numerous sources, newspaper clippings of male violence, it offered bits and pieces of information; there was little or no explanation, no interpretation. From that time on I began to think that women were afraid to speak openly about men, afraid to explore deeply our connections to them—what we have witnessed as daughters, sisters, grandmothers, mothers, aunts, lovers, occasional sex objects—and afraid even to acknowledge our ignorance, how much we really do not know about men. All that we do not know intensifies our sense of fear and threat. And certainly to know men only in relation to male violence, to the violence inflicted upon women and children, is a partial, inadequate knowing.

Nowadays I am amazed that women who advocate feminist politics have had so little to say about men and masculinity. Within the early writings of radical feminism, anger, rage, and even hatred of men was voiced, yet there was no meaningful attempt to offer ways to resolve these feelings, to imagine a culture of reconciliation where women and men might meet and find common ground. Militant feminism gave women permission to unleash their rage and hatred at men but it did not allow us to talk about what it meant to love men in patriarchal culture, to know how we could express that love without fear of exploitation and oppression.

Before her death Barbara Deming was among those rare outspoken feminist thinkers who wanted to create a space for women to talk openly about our feelings about men. Articulating her concern that the wellspring of female fury at men was making it impossible for women to express any other feelings than their sense that “men are hopeless,” she stated: “It scares me that more and more women are coming to feel this way, to feel that men as an entire gender are hopeless.” Deming did not feel that men were incapable of change, of moving away from male domination, but she did feel that it was necessary for women to speak the truth about how we think about men: “I believe that the only way we can get where we have to go is by never refusing to face the truth of our feelings as they rise up in us—even when we wish it were not the truth. So we have to admit to the truth that we sometimes wish our own fathers, sons, brothers, lovers were not there. But, this truth exists alongside another truth: the truth that this wish causes us anguish.” While some women active in the feminist movement felt anguished about our collective inability to convert masses of men to feminist thinking, many women simply felt that feminism gave them permission to be indifferent to men, to turn away from male needs.

When contemporary feminism was at its most intense, many women insisted that they were weary of giving energy to men, that they wanted to place women at the center of all feminist discussions. Feminist thinkers, like myself, who wanted to include men in the discussion were usually labeled male-identified and dismissed. We were “sleeping with the enemy.” We were the feminists who could not be trusted because we cared about the fate of men. We were the feminists who did not believe in female superiority any more than we believed in male superiority. As the feminist movement progressed, the fact became evident that sexism and sexist exploitation and oppression would not change unless men were also deeply engaged in feminist resistance, yet most women were still expressing no genuine interest in highlighting discussions of maleness.

Acknowledging that there needed to be more feminist focus on men did not lead to the production of a body of writing by women about men. The lack of such writing intensifies my sense that women cannot fully talk about men because we have been so well socialized in patriarchal culture to be silent on the subject of men. But more than silenced, we have been socialized to be the keepers of grave and serious secrets—especially those that could reveal the everyday strategies of male domination, how male power is enacted and maintained in our private lives. Indeed, even the radical feminist labeling of all men as oppressors and all women as victims was a way to deflect attention away from the reality of men and our ignorance about them. To simply label them as oppressors and dismiss them meant we never had to give voice to the gaps in our understanding or to talk about maleness in complex ways. We did not have to talk about the ways our fear of men distorted our perspectives and blocked our understanding. Hating men was just another way to not take men and masculinity seriously. It was simply easier for feminist women to talk about challenging and changing patriarchy than it was for us to talk about men—what we knew and did not know, about the ways we wanted men to change. Better to just express our desire to have men disappear, to see them dead and gone.

Eloquently, Barbara Deming expresses this longing when she writes about her father’s death: “Years ago now. It was on a weekend in the country and he’d been working outside with a pick and a shovel, making a new garden plot. He’d had a heart attack and fallen there in the loose dirt. We’d called a rescue squad, and they were trying to bring him back to life, but couldn’t. I was half-lying on the ground next to him, with my arms around his body. I realized that this was the first time in my life that I had felt able to really touch my father’s body. I was holding hard to it—with my love—and with my grief. And my grief was partly that my father, whom I loved, was dying. But it was also that I knew already that his death would allow me to feel freer. I was mourning that this had to be so. It’s a grief that is hard for me to speak of. That the only time I would feel free to touch him without feeling threatened by his power over me was when he lay dead—it’s unbearable to me. And I think there can hardly be a woman who hasn’t felt a comparable grief. So it’s an oversimplification to speak the truth that we sometimes wish men dead—unless we also speak the truth which is perhaps even harder to face (as we try to find out own powers, to be our own women): the truth that this wish is unbearable to us. It rends us.” As a young woman in my twenties who had not yet found her own powers, I often wished the men in my life would die. My longing for my father’s death began in childhood. It was the way I responded to his rage, his violence. I used to dream him gone, dead and gone.

Death was the way out of the fear evoked by the proclamation “Wait until your father comes home.” The threat of punishment was so intense, his power over us so real. Lying in my girlhood bed waiting to hear the hard anger in his voice, the invasive sound of his commands, I used to think, “If only he would die, we could live.” Later as a grown woman waiting for the man in my life to come home, the man who was more often than not a caring partner but who sometimes erupted into violent fits of rage, I used to think, “Maybe he will have an accident and die, maybe he will not come home, and I will be free and able to live.” Women and children all over the world want men to die so that they can live. This is the most painful truth of male domination, that men wield patriarchal power in daily life in ways that are awesomely life-threatening, that women and children cower in fear and various states of powerlessness, believing that the only way out of their suffering, their only hope is for men to die, for the patriarchal father not to come home. Women and female and male children, dominated by men, have wanted them dead because they believe that these men are not willing to change. They believe that men who are not dominators will not protect them. They believe that men are hopeless.

When I left home and went away to college, if I called home and my father answered, I hung up. I had nothing to say to him. I had no words to communicate to the dad who did not listen, who did not seem to care, who did not speak words of tenderness or love. I had no need for the patriarchal dad. And feminism had taught me that I could forget about him, turn away from him. In turning away from my dad, I turned away from a part of myself. It is a fiction of false feminism that we women can find our power in a world without men, in a world where we deny our connections to men. We claim our power fully only when we can speak the truth that we need men in our lives, that men are in our lives whether we want them to be or not, that we need men to challenge patriarchy, that we need men to change.

While feminist thinking enabled me to reach beyond the boundaries set by patriarchy, it was the search for wholeness, for self-recovery, that led me back to my dad. My reconciliation with my father began with my recognition that I wanted and needed his love—and that if I could not have his love, then at least I needed to heal the wound in my heart his violence had created. I needed to talk with him, to tell him my truth, to hold him close and let him know he mattered. Nowadays when I call home, I revel in the sound of my father’s voice, his southern speech familiar and broken in all the right places. I want to hear his voice forever. I do not want him to die, this dad whom I can hold in my arms, who receives my love and loves me back. Understanding him, I understand myself better. To claim my power as a woman, I have to claim him. We belong together.

The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love

is about our need to live in a world where women and men can belong together. Looking at the reasons patriarchy has maintained its power over men and their lives, I urge us to reclaim feminism for men, showing why feminist thinking and practice are the only way we can truly address the crisis of masculinity today. In these chapters I repeat many points so that each chapter alone will convey the most significant ideas of the whole. Men cannot change if there are no blueprints for change. Men cannot love if they are not taught the art of loving.

It is not true that men are unwilling to change. It is true that many men are afraid to change. It is true that masses of men have not even begun to look at the ways that patriarchy keeps them from knowing themselves, from being in touch with their feelings, from loving. To know love, men must be able to let go the will to dominate. They must be able to choose life over death. They must be willing to change.