The Willows at Christmas (24 page)

Toad could hardly believe it. “Mole

—

here!” Nothing could have lifted his spirits more than to think that the Mole was risking recapture just to give him moral support.

Ratty and Otter too!

Toad was oppressed no more. He rose up, climbed on to his metal stool, clutched the bars and addressed the baying crowd: “You see before you one who has been wrongfully accused and who…”

“Hush

—

‘e’s stopped thinkin’ and ‘e’s speakin’ again.”

“Ssh! Let’s ‘ear wot a villain says afore ‘e meets ‘is maker!”

“…one who stands trial on behalf of the oppressed folk of the Village!” continued Toad, his voice growing in confidence as the crowd fell silent, “Oppressed, I say, and broken!”

“‘E’s just

—”

began a weasel dismissively.

“Give ‘im a chance,” said a Villager, “give im an earin.

“Broken and beaten are those who live in the Village. But I shall not be broken or beaten so long as there are Villagers brave enough to come here to support me today!”

“Hear! Hear!” cried a Villager who had earlier been distributing rotten eggs and tomatoes from a basket for the crowd to throw at Toad.

“You, sir,” cried Toad, who like all demagogues on such occasions could be most impressive provided the quality of the thoughts expressed were not too closely attended to, “I ask you — I command you

—

to hurl those items of war not at me but at the weasels and stoats, who have sullied the Village with their presence!”

“We’ll have rather less of that, sir, if you please,” said the constable nearest Toad.

But it was too late, for the Village took Toad’s words as commands and hurled the missiles at the intruders.

In no time at all there was uproar, and as a posse of constables moved in to restore order Toad was hastily released from his cage and removed by way of the door marked “The Condemned” into the Court Room itself. There he was placed in the dock and chained to a metal eye bolted to the top of the dock.

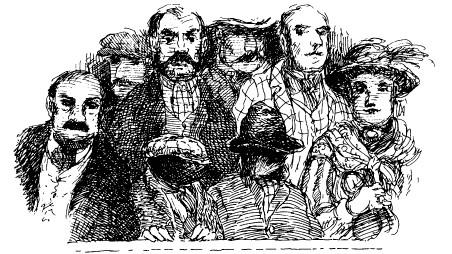

The Court Room was already half-filled with those gentlemen and ladies who had been able to afford the more expensive seats, and whose excitement had grown with the hubbub outside. When they saw Toad being escorted in they let out a strange gasp, and a good many ladies fainted right away to find themselves so close to such a villain.

His appearance seemed all the more criminal because a huge candle, of the kind normally used in church to light the way of sinners to holy communion, had been placed near the dock. It cast flickering shadows on Toad’s face and though he tried to smile and look respectable, it had the unfortunate effect of making him look like a gargoyle.

There were other such candles placed about the Court, and three or four flares on metal posts, which were useful augmentation to the light that filtered in through the smoke and dust from the high windows above.

The Parish Clerk was robed in black, and wore a wig. He was seated below the Judge’s Bench, with the dock to his right and near that, rather low down, a very few seats marked out as being for “Defence Witnesses”. But nobody was sitting there for Toad.

On the Clerk’s left hand, and facing the dock in such a way that their seats were elevated and formidable, were the Prosecution Witnesses. There were a good many of these, including the Chief Weasel, an ancient stoat and all the guests who had been at Mrs Ffleshe’s fateful Christmas luncheon.

Most formidable of all was Mrs Ffleshe, dressed that day in regal green silk and with enough jewellery to show that she was a woman of consequence, but not so much that she seemed flamboyant. Her face was powdered and in consequence a little pale, her eyes wide and pathetic. In short she looked just as she intended to look

—

as if she had suffered terribly at the hands of the accused.

Mrs Ffleshe’s hair, which was normally swept back in a severe style, had on this occasion been coiffured by a gentleman from Town who had softened its effect with ringlets and a chaste ribbon or two to match her dress. The effect of these contrivances was to make her more sympathetic to those who did not know her; to those who did, however, it was not far short of attempting to improve a wild, man-eating tigress from the jungles of Bengal by perching a dove of peace, stuffed, upon its head.

In the excitement caused by Toad’s arrival and the sudden inrush of ticket-holders who had been lingering outside, the disguised Rat, Mole and Otter took their places unnoticed in the shadows of the higher and more distant seats.

Soon the Court Room grew quiet with mounting expectation, and some trepidation too. The work of the specialist craftsmen the Clerk had mentioned to Toad and Mole was not yet fully visible, for the instruments of trial to which the accused must soon be subjected in the interests of justice were covered with dust sheets.

They had been assembled in the well of the Court, which, with the extra seating now stacked up about it, had the appearance of a bear-baiting pit. Here a spiked metal wheel was visible, there a thumbscrew or two.

In one corner, like a grotesque mummy from an Egyptian tomb, the sheets covered an upright figure with head and shoulders and a bulky body. This, the cognoscenti knew, was the Iron Maiden into whose spiked and brutal interior the accused must be placed for his own good.

How very eagerly the sharp tines of the instruments of trial pushed through their coverings; how positively the pulleys peered out, and the arms and legs of the racks waved their greetings; and how welcoming the grinning teeth of the prods and rakes; and how pretty the tresses of the iron chains and manacles!

In one portion of this dreadful pit two muscular gentlemen, clad in leather and masked, were tending a brazier of coals, which was sending into the atmosphere the scent of fire, smoke and brimstone.

The only way into this place of trial was from a little door that opened out to one side of the dock; the only way out of it appeared to be those dreadful worn steps that the Mole had observed some days before, which led to the door set high in the Court Room wall, and whose egress he knew to be a fatal plunge into the torrent below.

Only one other part of the Court Room attracted as much attention as the doleful pit of trial, and that was the Royal Box adjacent to it. It had been a considerable disappointment to the crowd that it had thus far remained empty, but as they heard the first chimes of eleven from the nearby church tower, a door at its rear opened, from which there was a brief show of light illuminating four plush red seats as two figures ascended from a little stairway and the door closed again, putting the box back into darkness.

“It’s ‘im, it’s the Prince!” cried several of the onlookers, and a mighty cheer spread about the Court. The Prince, a bulky gentleman, took a vantage point in his box from which he might view the proceedings, but, as royalty sometimes will, he stayed in the shadows, his servant at his side, their faces discreetly hidden so that the Judges might not be influenced by such expressions of support or contempt for the accused as they made.

When a spontaneous verse or two of the National Anthem was sung the Prince waved his hand in regal appreciation and seemed about to rise and bow when his servant put a restraining hand on his arm as if to say “Remember how Abraham Lincoln came to be assassinated and stay back in the safety of the box!” Then, with a nod towards the Parish Clerk, the Prince signalled that the proceedings should begin.

As the last stroke of eleven sounded the Parish Clerk banged his gavel and called everybody to order.

“Your Very Royal Highness, Lords, Ladies, Judges and Gentlemen, and ye yeomanry and tithe-payers of this Royal Village, mark ye that the Court Baron is now in session! Pray silence for the entry of the three Judges Nominal, namely Perspicacious, Purposeful and Pitiless, and His Lordship the Prosecuting Counsel!”

This was the signal for the entry of the Judges, all robed in black, followed by Lord Mallice, taller and gaunter than the others, who as Prosecuting Counsel sat with the Judges themselves.

One of the Judges took the central chair and he it was who spoke first, in a thin and aged voice.

“We are here to see justice done and we shall see it done. Remarks will be addressed to us as representative of the virtues of perspicacity in the affirmative, purposefulness in the neutral and pity in the negative. There being no counsel for the defence, the accused’s crimes being so wretched and dreadful, I shall ask Lord Mallice to proceed forthwith.”

“My Lords,” said he at once as if there was not a moment to lose. “In the dock you see the accused whose name is written on this sheet of charges.”

“He

is Toad of Toad Hall?” said one of the Judges, eyeing him.

“He is,” said Lord Malice.

“Can he speak and identify himself?”

“I can speak and my name is Toad,” said Toad in a firm voice which sent shivers down the spines of the ladies who had fainted earlier, “and since you ask, may I take this opportunity of saying a few words?”

“No you may not,” said Lord Malice, silencing Toad with a stare. “Parish Clerk, is the Court in order and its officials in place?”

“It is, My Lord,” said the Parish Clerk in measured tones, “which is to say

—”

“That is good,” said Lord Malice, sharply interrupting him to make quite plain he wished all replies to be brief.

“How does the accused plead?” enquired one of the Judges.

Toad swelled his chest and looked about him, readying himself for his first major speech.

“Guilty or not guilty?” enquired another Judge. “I was about to come to that, My Lordships,” said Toad, rising to the task, “because when I think about the word ‘guilty’ and ponder the word ‘innocent’, it certainly seems to me that

—

”Enter a guilty plea,” said the Judge Purposeful with impatience, “but let’s try him all the same.

Ignoring Toad’s attempts to speak, the Parish Clerk dipped his quill into a bottle of black ink and intoned, “G for Guilt, E for Even more guilt, U for Under a stone as in come from, I for not Innocent, T for Telling me! and Y for You, Mr Toad. Which is to say, ‘Guilty’.” The crowd clapped this performance loudly and the Judges nodded their heads approvingly.

“My Lords,” said Lord Mallice, “since the charges against this criminal are so many and varied, but all capital, I suggest we call the chief witness at once and proceeding from her testimony seek to discover through trials and tribulations of the condemned whether her evidence is true, and if so waste no more of the Court’s time than is necessary to satisfy us all that the prisoner is guilty

prima facie,

and if so — and it is our contention it will be

—

we may proceed at once to the second and final trial, which is execution, subject to your Lordships’ preferences as to manner, type, category and circumstance.”

“Agreed,” said the Judges.

“Call Mrs Ffleshe of Toad Hall,” said the Parish Clerk. Mrs Ffleshe, sighing heavily, weeping profusely and in need of support on both sides, was led into the witness box, where she was given a chair with a silk cushion and a decanter of water.

Her painful progress was the subject of silent and sympathetic scrutiny by the crowd, so that by the time she had sat down there was considerable unrest and a good many shouts of deprecation were aimed at Toad.

“Yer a brute for doin’ this to a fine lady!”

“Her bravery’s a match fer your cowardice any day!”

“Brute?” cried Toad, rising despite his manacles. “Why, that lady is

—”

“The prisoner will be silent,” said the Judge Pitiless.

Toad subsided and stared at Mrs Ffleshe.