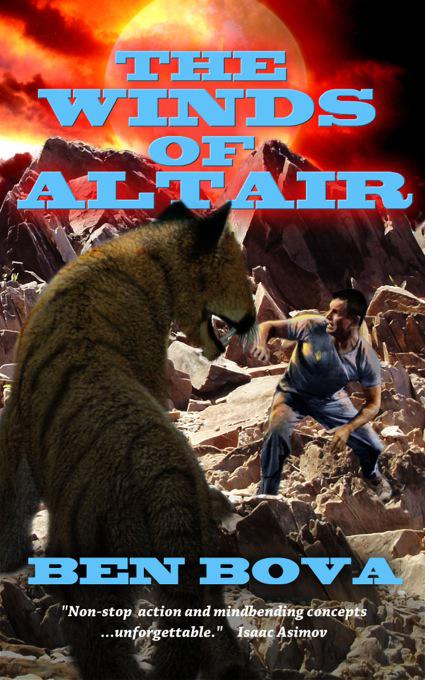

The Winds of Altair

THE WINDS OF ALTAIR

BY

BEN BOVA

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously.

THE WINDS OF ALTAIR

Copyright © 1983 by Ben Bova

An earlier, much shorter version of this work was published by E. P. Dutton under the same title in 1973.

All rights reserved.

A Tor Book

Published by Tom Doherty Associates, LLC

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10010

Tor® is a registered trademark of Tom Doherty Associates, LLC.

The Library of Congress has catalogued the first edition as follows:

Bova, Ben, 1932-

The winds of Altair/Ben Bova.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-523-48583-6

I. Title.

PS3552.084W5 1983

813'.54—dc 19

83160222

ISBN 978-0-7653-2831-1

EISBN 978-1-61824-916-6

First Edition: May 1983

Second Trade Paperback Edition: April 2010

Printed in the United States of America

0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Ebook version by Baen Books

http://www.baen.com

To Michael

CHAPTER 1

He knew that he was going to die.

Jeff Holman lay back on the couch, every nerve in him screaming with tension. He bit his lip to remain silent as the black woman sealed the cuffs that restrained his wrists and ankles, then fitted the gleaming silvered helmet onto his head.

He tried to pray, tried to remember the prayer for martyrs. But he couldn't. Somewhere in the crazy turmoil racing through him, he wondered if being killed by scientists counted as martyrdom. A martyr to secular humanists? He had never heard of that before.

The couch felt warm and soft, almost alive, as it molded itself to the contours of his body. The helmet, though, was cold, hard. It buzzed faintly with an electrical hum that Jeff could hear inside his head. The woman adjusted it carefully. Jeff looked into her face. It was utterly serious, grim.

With the weight of the helmet, Jeff could barely turn his head. Out of the corner of his eye he saw Dr. Carbo standing in the control room on the other side of the heavy plastiglass window.

Why me? Jeff asked himself for the hundredth time. The scientists had needed a student volunteer and their computer had picked Jeff.

He wanted to leap out of the couch and run away, or at least say something to them to show that he was not afraid. But his mouth was dry, his throat raw with fear. Scientific experiment, they had said. Absolutely necessary for the project. For the good of the Village. But Jeff knew better. The rumor among the students was that two of the scientists had already died in this laboratory, and a third was hopelessly insane. That was why they wanted a student "volunteer."

Finally everything was ready. The black woman moved away, out of his field of vision. Jeff heard the heavy padded door to the control room close softly and he realized that she had left him in this death chamber alone.

"All right, Jeff," Dr. Carbo's voice sounded louder inside the helmet than the soft-spoken Italian usually did. The faint trace of his accent came through. "Please try to relax; your blood pressure and other indicators are rather high."

Relax, sure, Jeff thought. Try praying. Try meditating. Nothing. His mind was a terrified blank.

"If there is any trouble," Carbo went on, "I will stop the test at once."

Sure, right away. As soon as I'm dead.

"Are you comfortable, Jeff?"

He started to answer, gagged slightly, then coughed to clear his throat. "Yes," he finally replied, weakly.

"Just close your eyes," Carbo said. "Pretend that you're going to sleep."

Jeff squeezed his eyes shut, knowing that they would never open again. He waited for . . . what? He didn't know what to expect. Pain? The warm glow of drugs? The oblivion that Nirvan promises but never delivers?

He saw little glimmers of light, patterns that drifted across his closed eyelids. The electrical hum of the helmet seemed to shift subtly, changing gradually until it sounded almost like the wind moaning across the desert scrubland of home. The patterns of light and darkness began to dance, vibrate. Starbursts flashed out painfully. His body tensed, jerked against the restraining cuffs, spasmed. Then he felt a cool tingling along his entire body, like a soft breeze.

It

was

a breeze.

He could feel it rippling the fur along his body. He could hear it as it sighed through the forest.

He opened his eyes.

He was sitting on his haunches at the top of a hill, sniffing the breeze for danger and food. Hunger was a deep dull ache within his massive body. But something more than hunger troubled him. Something was wrong, different. He growled, a thunderous rumble that came from deep inside his cavernous chest. Down at the foot of the hill, a malicious-looking snaky thing with feathers looked up sharply, hissed once, then flapped awkwardly into the air and flew into the trees. When a wolfcat growls, all other creatures flee.

He's made contact!

Jeff heard somewhere in his brain.

But it was a strange, alien voice from far away. It had nothing to do with him. He barely understood the words.

He rose from his sitting position, up onto all six legs, his claws digging into the grassy soil. Down at the bottom of the hill, where the forest began, in there among the trees, there was food. This hilltop was a good place,

his

special place, where he slept and brought his kills to eat. No other beast came to the hilltop when he was on it. And when he left, only the scavengers dared trespass—the lizard-hawks with their ugly crooked beaks and the small, scampering, yellow-eyed jackals whose teeth could crack bones.

He trotted majestically down the hillside, three tons of wolfcat, tall at the shoulder as a young tree, lean with muscle and hunger, moving as swiftly and silently as a gray cloud—a gray cloud armed with dagger-long teeth and claws like scimitars.

He's definitely in contact.

Can he assume control?

Wait . . . give him time. Don't push too hard.

The forest was a darker green than the hillside's open grass. Overhead, up among the swaying, sighing branches, clouds scudded by on the wind, dark against the brightness of the sky. The forest was almost as dark as night, but the whispering breeze brought a symphony of odors from the deep delicious woods: flowers and grasses and mosses and—most important of all—the scents of animals, of food, of the swift-footed antelope that fought with antlers and sharp hooves, the tasty little tree climbers, the shaggy, bristling diggers that stayed in their holes during the daylight hours.

It was early morning and the distant sun was only a bright patch in the sky, low on the horizon, sending long shadows out ahead of him. He saw his own shadow, the hulking immense shadow of a young male wolfcat loping across the meadow grass. Later in the day, he knew, Altair would be too bright to look at directly.

Altair.

The word seemed to belong in his mind, yet it felt odd, alien.

Into the forest he stalked, silent as a serpent, claws retracted now and every sense alert for food or danger. The older wolfcats—the fully-grown males who had many females and cubs—could laze during the day and let their females do the hunting for them. They defended their cubs and their hunting territory, and did little more. Young wolfcats had to hunt alone until they were strong enough to challenge an adult for one of his younger females.

He glided through the underbrush silently, his immense bulk slipping through the trees like a wraith. The stream is where the prey will be. He was downwind of the stream; already he could smell the antelope drinking there, but they could not catch his scent as he approached. Good. His empty stomach drove him forward.

You're not going to let him stay

and . . .

I hadn't intended to, but he seems so well-linked with the beast, I'd hate to pull him back now.

But . . .

It's okay. If he's going to work with the animal he's got to allow it to eat.

Strange sounds, he thought. Buzzings, like insects flitting near. But these buzzings were inside his head.

With a shake of his massive mane, he advanced carefully, slowly now, through the underbrush that carpeted the forest floor. He could hear the gurgling of the stream, not far away. He flattened out in the brush, belly to the ground, and inched forward. Then froze. Six of the antlered grass-eaters were standing at the stream's edge, their sharp hooves in the cold racing water. Some of them would bend down to drink while their fellows stayed erect and alert, probing the forest nervously with large wary eyes and erect twitching ears.

Suppressing a growl, he bunched his muscles and got ready to spring. When the nearest one puts down its head to drink . . .

He leaped out of the brush, a gray streak of death aimed at the nearest antelope. His shattering roar froze them all for a split-second, but then they bolted off in all directions, bounding and springing through the underbrush. His intended prey jumped too, but straight ahead, into the middle of the stream. The water was shallow but swift, the footing uneven and slippery. The antelope stumbled. That was all the advantage that a wolfcat needed.

He touched the ground once with his six clawed paws, then leaped again and landed on the antelope's back. A slap of a forepaw broke the creature's neck while his mid-and hindpaws grasped the animal's meaty body firmly. They fell together with a splash.

He scrambled up and dragged his prey to the stream bank, using both forepaws and walking on his hind-and midlegs. The smell of blood, of meat, was overpowering. Raising his great black-muzzled face to the sky, he bellowed out a roar of triumph that shook the ground.

Stop it! Stop it! Get him back!

Yes, of course, you're right. No need to let him take part in the feasting. Terminate.

CHAPTER 2

Jeff opened his eyes and was back aboard the ship. He knew that his body had never left the couch, and yet—he shuddered.

They hadn't killed him. They had turned him into . . . into an

animal.

A powerful, bloodthirsty, hunting beast. They had taken his mind, his awareness,

himself,

and turned him into a wolfcat down there on the surface of this hell-hole planet they were orbiting.

An animal. Jeff felt himself trembling uncontrollably. He knew they were going to do it. They had explained it all to him for a week before they tried this test, yet the shock of its reality made him feel weak. They turned me into an animal, he repeated to himself.

And it had been exhilarating. The power of that beast! The strength of him. The thrill of hunting down that antelope and

getting

it.

The woman unstrapped his wrists and ankles while Dr. Carbo carefully lifted the helmet off his head. Jeff did not move; he felt exhausted.

The woman looked into his eyes searchingly. "Are you all right?" she asked.

Her name was Amanda Kolwezi, Jeff knew. She was rather good-looking, even though she was black. Not really black, he noticed for the first time. Her skin was more the color of the giant tree boles down on the planet, a rich dark brown. High cheekbones. Eyes that looked almost oriental.

"Jeff," she repeated, "are you okay?"

"Yes." He tried to nod his head. "I'm okay." But his voice was weak, little more than a whisper. He felt drained, almost helpless. Yet terribly excited.

Dr. Carbo came up beside her, smiling at him. "Just take it easy, Jeff. You did a fine job. Very good work."

Jeff started to sit up on the couch but everything seemed to sway around him. The room started to slide off at an angle and he fell back onto the soft padding.

"Jeff!" Amanda grabbed his arm.

"It's all right," Carbo said. "A little disorientation. It's to be expected. He'll be okay in a minute or two."

But he turned and stared worriedly at the monitoring panels against the wall. Jeff knew that they kept track of his body's condition: blood pressure, temperature, pulse, things like that.

For a scientist who was so important to the Village, Dr. Carbo did not look impressive to Jeff. He was short, actually a shade shorter than his assistant, Amanda; round-shouldered, round-faced, his thinning brown hair always looked like he'd just stepped in from a windstorm. He was soft-looking, even his voice was a soft tenor. His normal posture was a slouch, where Jeff expected the kind of ramrod stiffness that his teachers and Elders inculcated. Instead of the drab gray coveralls that all the students wore, this scientist dressed himself in bright-colored tunics and comfortable slacks that made him look slightly like a round little clown. Dr. Carbo's face had a brownish swarthiness to it, and he was a little jowly, with the darkish shadow of stubble across his chin, like somebody who shaved himself instead of using the treatments that kept a man's beard from growing for months at a time.

Maybe the treatments don't work for everybody, Jeff thought. Or maybe scientists don't believe in them. As a Believer, Jeff followed his Church's rules and kept his face bare. Only the Elders were allowed to grow a beard. Of course, Carbo might be a Catholic. Jeff had no idea what

they

believed.

Amanda came to him with a cup of steaming liquid in her hand. "Here, Pathfinder, drink this."

"Pathfinder?"

She grinned at him. "Look it up in the library. It's a book you ought to read."

A book. He shrugged and accepted the cup from her hand. Strange how the back of her hand was so dark, yet the palm was perfectly pink. The liquid felt warm and good. Jeff wondered how the raw meat of the antelope, still blood-hot, would taste. The thought startled him, jarred him so thoroughly that he almost dropped the cup. Neither Carbo nor Amanda seemed to notice, though.

"How do you feel now?" she asked.

"Okay . . . I guess."

Dr. Carbo nodded and headed back for the control room. Jeff drained his cup and put it down on the couch's headrest.

"Think you can stand up now?" Amanda asked.

"Yeah. Sure."

She slid her arm around his shoulders and helped Jeff to his feet. He stood uncertainly for a moment, finding that he actually was enjoying the nearness of her, the touch of her hands, the scent of her skin. Jeff had never been this close to a black woman before. Back home, in the Church-run housing enclaves with their shrubbery-decorated electrified walls and laser-armed security systems, blacks were the equals of whites—so equal that they lived in their own enclaves, went to their own schools, and even prayed in their own churches.

With Amanda at his side, Jeff walked on spongy legs out of the small laboratory chamber with its stainless-steel walls and plastic-tiled flooring, through the open door to the control room. The walls were soft-textured there, the floor thickly carpeted. Dr. Carbo was sitting at the central console, talking on the picturephone to a narrow-eyed, white-haired, bony death's-head of a man. Jeff recognized him instantly: Bishop Foy, chairman of the Council, the unquestioned leader of the Village.

"He's made solid contact with the animal," Carbo was saying. "If we can establish that good a contact every time, we can use this wolfcat and then go on to adapt other animals."

Bishop Foy's lips pulled back in something approaching a smile. His big uneven teeth made him look even more like a skull. "Do you believe that other . . ." he hesitated, noticing that Jeff had entered the control room, ". . . other students will be able to establish contact with the creatures down there?"

Carbo made a vague gesture with his right hand. "We shall see. If one student has done it, it stands to reason that others should be able to do so."

Jeff felt a pang of anger at that. He didn't know how many of the scientists and Elders of the Village had tried to make contact with the animals down on the surface of the planet. He had been the first to succeed. Instead of congratulating him, they were saying it wasn't anything so special. If he did it, others could. With the anger, though, came an instant reflex of guilt. Pride, Jeff told himself. Sinful pride. He offered a swift, silent prayer to Nirvan. But the prideful anger still simmered inside him.

"So your conclusion is that this test was a complete success," Foy said. His voice was thin and scratchy; it sounded irritable, as though even this good news annoyed him.

Carbo answered, "A success, yes, of course. But we don't know yet if he can control the animal."

"I understand. But he did make firm contact. All the sensory inputs came through? Even visual?"

"Yes," Carbo replied.

"Then the animals aren't blind, after all."

"Those scaly-looking areas across the top of the head are infrared receptors. We knew that. Apparently they have a visual cortex and can see in the infrared wavelengths, where we can't."

Bishop Foy nodded silently.

"Polchek and his zoologists will want to bring a wolfcat up here to dissect," Carbo muttered.

But Foy's thoughts were elsewhere. "The crews who've been down to the surface reported that vision is nearly useless there, even with infrared sensors. The cloud cover blocks out all the sunlight. You can't see more than five meters ahead. Your sense of distance and direction goes haywire."

"Our sensors must be set at the wrong frequencies," Carbo answered. "Come and look at today's tapes. When we see through the animal's eyes everything is bright and clear."

Foy blinked his narrow, deepset eyes and said nothing.

"If a wolfcat were brought to Earth," Carbo went on, his soft voice picking up speed with enthusiasm, "it would probably be just as blind as we are on Altair VI."

"Perhaps. Perhaps," Bishop Foy replied impatiently. "Bring the tapes to my office as soon as you can. There are many details I must discuss with you, in private."

The picture screen abruptly went blank.

Carbo stared at it for a moment, then made an elaborate shrug that took in his shoulders, arms, hands, and even the expression on his face. He turned to Amanda and said, "Make sure he gets plenty of food and rest. He has a lot of work ahead of him."

Amanda gave a small sigh and motioned Jeff toward the door that led out of the control room. Jeff went with her, feeling more like a laboratory animal than a human being. I wonder if they're going to dissect my brain when this is all finished? he asked himself.

The official name of the ship was

Melvin L. Calvin

, but the five hundred students, Elders, and scientists aboard called it simply, the Village.

It did not look like the sleek starships Jeff had seen on video shows, nor like the ungainly rockets that had explored the Moon and the planets of Earth's solar system—all of which were so far away now that the Sun itself was no more than a pinpoint of light, one of the millions of stars that could be seen through the ship's viewports.

The Village was a cluster of globes, bubbles of plastic and metal linked by spidery tubes. It had no front or back in the usual sense, no up or down. Each globe housed a few dozen people, or was a facility of some sort: a library, a meeting hall, a grassy park lined with trees.

In actuality, the Village was like a barge or a houseboat that had no real propulsive power of its own. It had been towed from Earth to Altair VI by a squat, stubby vehicle that was little more than a massive engine with a tiny bubble of living quarters for its crew: Captain Olaf Gunnerson, his son, daughter, and son-in-law—and their computer.

Gunnerson was a professional star-sailor, and his vehicle was nothing more than a tugboat. But it was a tug that could span interstellar distances, for a fee.

His engines were gravity field drives, not rockets. Generating the kind of gravity warps made in nature by Black Holes, the gravity field drive allowed the human race to expand outward among the stars—again, for a fee.

The first to go had been robots, of course. Riding the earliest gravity field ships, they had explored the dead gas giant worlds of Barnard's Star and returned in less time than it took light to span the distance. Physicists argued bitterly over whether or not the gravity drive actually propelled the ships faster than light. One of the rock-bottom principles of the universe was being shaken, and campuses all over Earth trembled with the ferocity of the debate. The younger physicists declared that Einstein had been overthrown. Their elders insisted that this was not possible; even though the ships had

seemed

to go faster than light, what had actually happened was that the gravity warp had bent spacetime so out of shape that the ships left the universe momentarily and then re-entered it elsewhere, lightyears away.

The politicians didn't care which way the physicists decided. They now had a tool in their hands that they could use.

"Colonize the stars!" they cried.

They started to build starships, to be filled with the poorest, most ignorant, least desirable people of Earth. "Export your problems," they whispered to one another. "Send them off to where they'll never bother us again."

But before they could do that, before they could exile the unemployed, the uneducated, the untouchables, they had to send out their best and their brightest—to pave the way.

The least desirable people of Earth could not be launched out into the interstellar void to fend for themselves. Not even the politicians were that insensitive. Robot ships were built to find Earthlike worlds, and then teams of the eager, bright, idealistic young men and women of Earth were sent to prepare these worlds for the colonists to come.

To

these

young men and women, the politicians sang of challenge and commitment. "Tame the new worlds!" they urged. And the eager, bright, idealistic young men and women took up the challenge. Just as the politicians' social technicians had predicted they would.

Jeff made his way back to the dome where he lived. He was twenty-three years old, an undergraduate degree in meteorology freshly awarded him. He had been aiming for a doctorate in weather modification when the call to "Tame the new worlds!" had overtaken him. After six months in the Village, he wondered if he had chosen wisely.

He was slightly taller than average, yet no one thought of him as "big," not even he himself. Jeff had the broad shoulders and strong arms of a farm boy, and a slow, easy smile that often prompted strangers to think he was easy-going, perhaps even lazy. His hair was dark and thick, his eyes the gray of a stormy sea. His psychological profile showed him so close to all the norms that the social technicians thought him dull (only the psychologically weak or unusual interested them). They were quite surprised when their own computers picked him as the student best qualified psychologically to attempt making contact with one of the animals of Altair VI.

He lived in one of the Village's domes with nearly three dozen other students. They were all within a year or two of his own age. Half of them were women. All of them, naturally, were reliable Church members, Believers who had been sent by their Church to tame this new world for all the Believers who were to come as colonists.

All the students had taken vows of celibacy as a matter of course, just as they had while on campus. Sex was a powerful weapon for either good or evil; it had to be channelled properly.

Their vows were duly registered with Bishop Foy, the spiritual and temporal leader of the Village. The vows were also protected by the network of security cameras that watched every dormitory room, every meeting hall, every corridor and chamber of the Village. And the cameras were backed up by dorm mothers in each of the Village's residential domes. The dorm mother in Jeff's dome was a flour-white giantess with the unlikely name of Bettina Brown. The students had quickly dubbed her Brunhilda. She was flaxen haired, fully two meters tall, almost as wide, and strong enough to pick up two students Jeff's size, one in each ham-fisted hand, and shake them until their teeth rattled.

Between Brunhilda and the computer-monitored sensors, Jeff and his dorm mates had little chance for mischief. And little time. Their hours were filled with work, study, and prayer. Even though the gravity field drive made the jump to Altair almost instantaneously, Gunnerson's tug had to tow them for two months out to the edge of the solar system before the jump could be made, and then for two more months they spiralled inward to take up an orbit around the sixth planet of Altair.