The Witling

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Notice

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-one

Books by Vernor Vinge

ABORTED RESCUE …

About the Author

Copyright Page

To Joan D. Vinge, for all her support

in the writing of this novel

F

all had come to Bodgaru-by-the-Sea, and winter was not now far away. All up the sides of the mountains that sheltered Bodgaru’s northern flank, the tri-crowned pines stood green and snowy white in the fading sunlight. The town itself was still free of snow, but the cutting edge of the sea wind blew up off the beaches to lay sand and dust across the frosted brown grass that separated the townspeople’s stone houses. Only the furry terns were about in the out-of-doors these days: they screaked and scrawked as they glided between the houses. The townspeople were Summerfolk, and when the weather turned cold, many of them moved south where summer was forever. Those who stayed kept indoors, and worked their mines buried thousands of feet within the mountains.

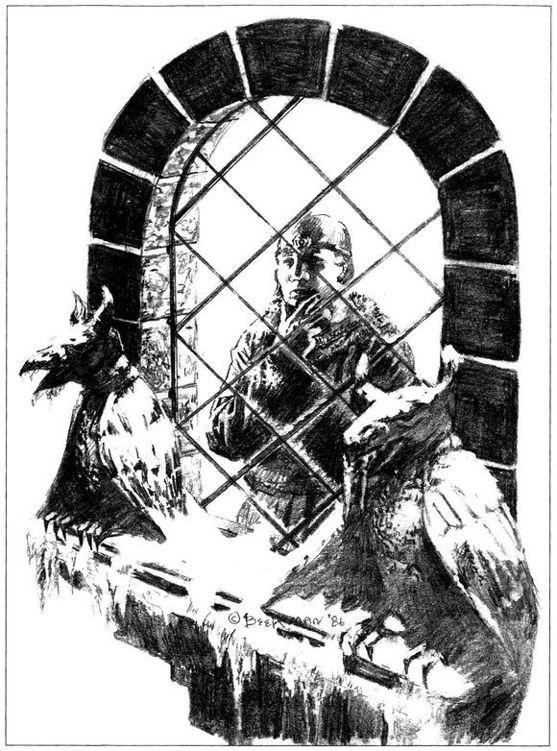

Parapfu Moragha looked out upon the scene, and silently cursed the day he had been appointed prefect of Bodgaru. Oh, at the time it had seemed quite a coup. His stone manse sat large and imposing on the ridge line that shielded the terminus of the Royal Road from the mountains to the north; he ruled a land larger than some duchies. But his vast “domain” was a cold, ugly borderland of the Summerkingdom. Bodgaru was seven leagues north of the equator—a short ride on the road, but more than two thousand miles as pilgrims walk it. The glaciers and mountains and snow-covered deserts that stretched from Bodgaru away to the North Pole were all claimed by the Snowking.

Moragha turned away from the thick quartz window to eye his visitors with barely disguised distaste. A half-wit, a Guildsman, and a common miner. It was outrageous that he should be bothered by the likes of these on the eve of the prince-imperial’s visit, a visit that might be his last chance to persuade his friends at court to get him a new assignment. He eased himself onto the fur cushions that covered his stone chair, and said, “Really, Prou, why

are

you here?”

Thengets del Prou returned his accusing look with characteristic blandness. Only the glint in his eyes told Moragha that the tall, dark-skinned Guildsman was really laughing at his discomfiture. “I am within my covenanted territory, My Lord. Bodgaru is less than eight leagues from Dhendgaru.”

Theso Lagha, first speaker of the miners’ association, bobbed his head respectfully. He, at least, showed proper courtesy. “I asked him to come here tonight, My Lord Prefect. It seemed to me that what Hugo saw was important, so important that you might need the Guild immediately.”

Moragha grimaced. Covenant or no, he feared the Guild. And he trusted Prou even less than the average Guildsman; the dark-faced smart aleck was of desert stock, with a practically unpronounceable name. Moragha wished that the miners didn’t need Prou’s senging quite so often, that the Guildsman would stick to his assigned city. “Very well, good Theso, just what did your man see?”

Lagha urged the third visitor toward Moragha’s throne. “Yes, My Lord. Hugo here is indentured to our association as a woodcutter. Tell My Lord Prefect what you saw, Hugo.”

Hugo was obviously a half-wit and a witling. His eyes wandered aimlessly about the room as he fiddled nervously with the sewn bladders of his slicker; Lagha and Prou at least had the grace to leave theirs by the pool. After several incoherent garglings, the old man finally managed: “May it please M’lord, I cut wood … for freeman and his friends, them that pull the rock from the hills. Mostly, I cut tri-crown pine over … over …”

“Over northeast of town, away from the prospecting hills,” put in Lagha.

“Yea … nice up there. No people. No things, excepting paddlefeet sometimes … and that only after the snow comes all the way into town … .” He paused for a long moment but his owner did not prod him on. Finally he recovered his chain of thought. “ … But this last nineday, before the first snow, there’s been some … thing so strange up there. Lights, faint. Like you see over Bilala’s marsh at night sometimes in the summer. I thought it might be same thing, but no, the lights stay and stay. Pretty. I go closer last night. Come in from the north … . Quiet, quiet. There are people there, M’lord, watching us, watching town.”

“How many?” snapped the prefect.

The witling’s face twisted in concentration. “Hard to say. Two, I think … they have a little house there and they sit and watch us from inside. And they’re strange. One’s so big, so tall … much taller even than the honored Guildsman.” He nodded at Thengets del Prou. “ … I go close, closer, quiet like the paddlefoot, and then …”

His voice faded, as he stared beyond the thick stone walls at some remembered vision. Faintly, the prefect heard the wind keening through the twilight outside. He shivered. This place was so far north of where decent men should live. “Well?” he asked finally. “What happened then?”

“I run. I run! I’m so scared.” The old man collapsed blubbering onto his stone chair.

Moragha turned on Lagha. “For this you waste my time, freeman? Don’t you know that the prince-imperial”—

the witling, boorish prince-imperial—

“arrives in the Bodgaru prefecture tomorrow? I have more important things to do than listen to the ravings of your village idiot!”

Lagha’s civility faded the tiniest fraction. “My Lord Prefect, Hugo has certain—problems, but he has been the property of my association for nearly thirty years, and in all that time I don’t believe he has ever told tales.” The object of their discussion sat looking dismally at the floor. “Frankly, My Lord, I believe he saw

something

up there.”

“Squatters?” asked Prou.

“I don’t know, sir. There are things that don’t fit: the creatures are very strange, by Hugo’s telling. That’s why I thought My Lord Prefect might want to commission you to seng the hills. If there’s a number of Snowfolk squatters up there you would detect it. And if these strange things be something else …” His voice trailed off.

Moragha wondered briefly why the bad luck always happened to him. The prince-imperial was an untalented lout, a stain upon the royal family’s honor, but he

was

first in line of succession, and he

was

visiting the prefecture tomorrow. That visit was very important to Parapfu Moragha. But now there was this new problem to worry about; it just wasn’t fair. On the other hand—and here the prefect brightened—in the unlikely event that there were Snowfolk close to town, his detecting them on the eve of the imperial visit would indeed be a coup … . Even if he had to deal with the Guild to achieve it.

“Well,” he said grumpily to Thengets del Prou, “will you reconnoiter that area for us?”

Prou stretched his long legs lazily toward Moragha’s throne. “You know the Guild doesn’t like to involve itself with disputes between kingdoms.”

“But we don’t know for sure what it is Hugo saw up there,” said Lagha.

“True,” said the Guildsman. “Very well, My Lord Prefect, I will take the job. The Guild’s commission will be one hundred imperials.”

Moragha started. That was ten times the usual seng fee. “Go to it, then.”

Prou nodded, closed his eyes, and seemed to relax even more. There was a long silence as the dark-faced young man senged far beyond the manse. Moragha closed his own eyes. He had always prided himself on his Talent. He could easily perceive the densities of the rock and air beyond the walls of the manse. His artisans had arranged the flagstones about the building in subtle patterns of varying density, and every part of that design was clear to him. Beyond that he could seng several transit pools in the area, but the spaces in between were hazy, and without visiting them personally he never could quite place them in true space. That was the only real difference between himself and the likes of Thengets del Prou, who even now was perceiving densities thousands of yards up in the hills. Moragha tried to imagine what it must be like to have such omniscience—but as always, he failed.

Finally the Guildsman opened his eyes. For a moment he seemed disoriented. Then, “You just wasted one hundred imperials, My Lord Perfect,” he said. “I senged nothing up there but the densities of snow and rock.”

There was something strange in the other’s expression, and Moragha struggled for a moment to identify it. There was no laughter behind Prou’s dark eyes! That was it. For the first time in the nearly two years he had known the man, that ironic glint was gone. The Guildsman had senged something, something so important he was willing to break the Guild’s bond to lie about it. Moragha suppressed a sneer, and said, “Thank you, good Thengets, but I think I will check further. The Royal Atsobi Garrison is only one league to the south. I can have a company of mountain troops up here in an hour. Freeman Lagha, you’ll have your Hugo direct the imperial soldiers. Any questions or comments?”

Moragha raised his hand in dismissal. Lagha retired with Hugo to the salt water pool at the center of the room and departed. The prefect stood as the Guildsman prepared to slip into the water after them. “A moment, good Thengets.”

“Yes?” The Guildsman had recovered his old composure. There was even the beginning of a faint smile on his face.

“Are you sure you didn’t miss anything on your survey?”

“Of course not, My Lord. You know it’s nearly impossible to detect objects as small as individual men—their densities are so much like water. But there is no large group up there, I assure you.”