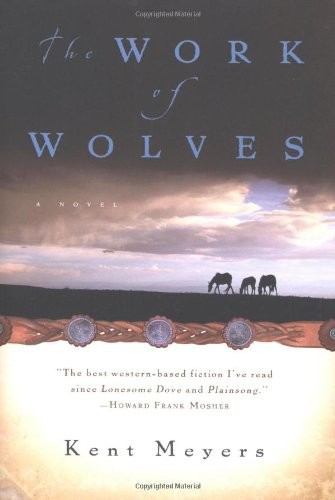

The Work of Wolves

Kent Meyers

A Harvest Book

HARCOURT. INC.

Orlando Austin New York San Diego London

Copyright © 2004 by Kent Meyers

All rights reserved. No part of this publication

may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means,

electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording,

or any information storage and retrieval system,

without permission in writing

from the publisher.

Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the

work should be submitted online at

www.harcourt.com/contact

or mailed to the following address: Permissions Department,

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company,

6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, Florida 32887-6777.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Meyers, Kent.

The work of wolves/Kent Meyers,

p. cm.

1. Triangles (Interpersonal relations)—Fiction.

2. Ranchers' spouses—Fiction.

3. Horse trainers—Fiction. 4. South Dakota—Fiction.

5. Ranch life—Fiction.

I. Title.

PS3563.E93W67 2004

813'.54—dc22 2003026365

ISBN 978-0-15-101057-8

ISBN 978-0-15-603142-4 (pbk.)

Text set in Dante

Designed by Linda Lockowitz

Printed in the United States of America

First Harvest edition 2005

H J L N O M K I G

PrologueIn memory of

Tom Herbeck and Stewart Bellman

W

HEN HE WAS FOURTEEN YEARS OLD

, Carson Fielding, having just received his driver's license, walked outside on a fall morning, threw his schoolbooks into his father's pickup, climbed in, started the engine, drove around the Quonset hut, backed up to the horse trailer, got out, wrestled the horse trailer hitch over the pickup's ball hitch, snapped the coupling, climbed back into the pickup, eased the rig over the ruts the tractors had dug into the gumbo during the spring rains, and clanged away up the driveway. His parents were finishing coffee. They heard the empty trailer boom. They scraped their chairs back and watched through the kitchen window as their son turned north on the county road, going away from the school in Twisted Tree.

"What's that kid doing now?" Charles Fielding exclaimed. He banged his cup down, sloshing coffee on his forearm, and reached for his hat. But Marie Fielding stilled him with a hand to his shoulder. She took the dried and stiffened dishrag hanging on the kitchen faucet and dabbed his forearm, then moved the rag in a slow circle on the counter.

"He'll come back," she said, leaning down to watch the pickup and trailer disappear over the top of the first hill to the north, leaving a scrim of brown dust against the morning sky. A strand of hair fell over her eyes. She brushed it back, held it as she watched the dust thin and disappear.

"But where the dickens is he going?"

Marie Fielding began to gather the breakfast dishes from the table. She picked up the plates, balanced the silverware and cups on top of them, brought them to the counter. Outside, Carson's grandfather appeared in the frame of the window, coming from the old house. He walked to the middle of the driveway and stood gazing northward, his blue jeans crumpled around his boot tops, barely hanging from the belt above his narrow hips.

"I don't know," Marie said. She nodded at the old man standing in the driveway. "But I'll bet Ves does."

Charles Fielding stared at his father.

"No doubt about that," he said grimly.

He turned away from the window, rammed his hat onto his head.

"Charles."

But her husband strode across the floor. She listened to the back door open, then thud. She stood looking down at the pile of dishes. The stack of cups trembled. She reached out, touched the top one, then removed it from the stack, set it by itself on the counter. Rotated it, watched the handle point one way, then another.

Through the walls she heard the old Case tractor turn over, then stop, then turn over again. She stopped breathing, waiting. Her thumb and forefinger stilled the cup, as if she were going to lift it, sip the emptiness there. Then the tractor coughed and roared, and she breathed again. She opened the hot water tap and held the dishrag under the faucet. The rag's stiffness dissolved in her hand. She dropped it, reached out, dipped the cup into the suds. On the driveway her father-in-law turned his head in the direction of the running tractor, then looked back again at the hill over which the horse trailer had disappeared.

CARSON RETURNED IN THE EARLY AFTERNOON

with his first horse. He'd driven fifteen miles to Magnus Yarborough's ranch to buy it. When the wiry, sandy-haired adolescent with the thin nose stepped from his stonepitted pickup and announced: "I'm Carson Fielding. I called about the horses," Magnus Yarborough checked his watch. The deep and confident voice on the phone the other day had said its speaker would be out at ten, and this kid had the same voice and claimed the same name. Still, Magnus had expected an adult and couldn't believe this was the same person. But his watch read 10:05, and he kept it set five minutes fast so he wouldn't be late for things, and the kid was sure enough standing in his driveway.

"Well well," Magnus said.

He didn't put out his hand. He'd anticipated a hard bargain when he'd heard the voice on the phone, and now his anticipation had turned into a joke, but it was a joke only he'd get. He was going to fleece this kid. It was in the nature of things, the way runoff follows a draw. Magnus walked around to the passenger side of Carson's pickup, got in, slammed the door, and waited for Carson to understand that he was meant to get behind the wheel and drive and follow directions.

The horses were pastured five miles away. Magnus and Carson didn't say a word to each other during those five miles. A prairie falcon left a power pole and flew low over the orange-brown expanse of a milo field, and a hen pheasant came out of the road ditch grass and returned. A jet labored across the sky and disappeared, and its contrail disappeared. But other than those things and the racket of the empty trailer and Carson's hands moving on the steering wheel and the rustle of Magnus's jeans shifting on the cracked upholstery in a quiet abrasion of denim on vinyl, nothing happened. By the time they got to the pasture, Magnus had convinced himself he was about to do Carson a favor, teach him a lesson that might keep him from being ripped off in a big way when he was older. The kid ought to be in school, so why not school him?

"Here," Magnus said, and nodded at a field approach. Carson turned off the gravel road and stopped the pickup with its bumper nearly touching a gate made of four strands of barbwire.

"Go ahead. Open it," Magnus commanded.

Carson stepped from the pickup, leaned hard against the post that stretched the four strands of wire, flicked up the loop of smooth wire that held it to the anchor post, leaned the loose post down, pulled it out of the bottom loop, and carried it into the pasture, the barb wire catching and scraping in the grass. He returned to the pickup and, still silent, drove into the pasture.

"You weren't thinking you should shut that gate?" Magnus asked.

"Ain't no need."

It was true. The horses, below the hill, weren't about to sneak past the pickup and escape. But it irked Magnus that the kid had decided that for himself. Before he could reply, though, the pickup crested a rise and stopped. A herd of twenty horses appeared below, standing in yellowgreen grass, all of them looking up. Then the kid spoke what ought to have been Magnus's words.

"There they are."

"They sure as hell are," Magnus growled. The kid acted like he was pointing them out as a species that Magnus had never seen.

But Carson had opened his door and was stepping out. Magnus's words flitted right past him. By the time Magnus realized the damnfool kid was going to walk down the hill to look at a bunch of half-wild horses, the kid was twenty yards away.

"Kid! You can't just."

But Carson continued down the hill.

"Christ!"

Magnus stepped to the ground and started after the kid but found himself strutting through the grass with his butt pointing this way and that—reminded himself of those racewalkers he'd see in the Olympics, looked like they had a sandbur between their cheeks they were trying to shake. And Magnus would be damned if he was going to run. He stopped, figured he'd at least take some pleasure in watching the horses spook. Maybe the kid was dumb enough to take off running after them, a goddamn track star in cowboy boots.

But the horses didn't run. The kid got closer than Magnus had ever been to the bunch, and the horses did not spook. But then, there it was. A shiver ran through the herd, as if a cloud of passing wasps had touched each animal briefly in its passing. The horses were going to break. A roiling would now go through them, as of disturbed water, some great thing moving beneath the surface. There would be a moment of confusion, animals cutting through each other's paths, all positions changed, and then the herd would be gone, their tails strung behind, lifting the earth from itself with their hooves. The kid would be left standing in the dust.

But right then he lapsed into stillness—not the sudden, rigid stillness of a frightened animal but the stillness of a boat cutting power, a stillness that seems an extension of movement, another kind of floating. It suspended the whole herd. Magnus's mouth dropped open. The kid stood on the hillside and looked at the horses, close enough to throw out a long rope and snare one, close enough to breathe their breath and the evaporation of their pores. The horses churned and eddied. But didn't run.

Then the kid was walking up the hill again, right up to Magnus, and stopping and turning and looking down at the horses for a while. He pointed with his chin.

"I guess maybe that roan there."

"What roan where?"

"One out there at the edge a the herd. Watchin us."

Christ on a crutch—the kid walks down the hill like he's going to look at horses and puts on a damn good act of looking and then walks back up and says he'll take the sorriest-ass piece of horse meat down there, a rawboned, knobheaded, razorspined, wildeyed, stiffkneed, stupidass yearling that probably couldn't be broke, and if it could it'd put you on dialysis in a year, shaking your kidneys up with that gait, and bite you if you turned your back, just for something to do.

Let school begin.

"Cost you some money, that horse will," Magnus said. "I don't mean any insult, but you're young, that's not too hard to see, and I wonder if maybe that horse is a bit more than you can afford."

Fools inspired him. If the kid's dumb enough to show a preference for a horse, go along with it. Pretend it's better than even he thinks. If one of those Greek muses wasn't named Idiot, it sure ought to have been. Thinking these things, Magnus missed for a moment what Carson had said.

"If I can't afford that one, I can't afford any of 'em. Hafta shoot one a them other horses to make it cheaper'n that roan. Several times. Just to be sure."

Before Magnus digested the meaning of this, Carson was saying something else:

"I don't mean a be tellin you your business, sir." He was looking at Magnus now, and he'd turned into the ugliest damn kid Magnus figured he'd ever seen, gangly as hell, with sandy-colored eyebrows that didn't quite do the job of pulling his eyes in and keeping them from staring. He was polite as all hell, but Magnus couldn't hardly think with those pale eyes gazing at him and that polite voice going on.

"I mean, they're your horses'n all. An if you want a sell me one a them other ones, alive, for less'n I want a pay for that roan, that's your business. But the truth is, I don't know if I ever seen a more worthless animal since I been born. Which, I admit, maybe ain't that long."

For the first time since he'd started buying and selling things, Magnus Yarborough had no words. Always have words was his rule. Always have something to say. It didn't matter what, as long as he opened his mouth and let something come out, for distraction's sake if nothing else. But, staring at Carson, Magnus felt that if he opened his mouth he'd talk in word soup, like he'd once heard from a homeless schizophrenic man in Denver, a meaningless babble that drove Magnus crazy as he walked along behind the man, trying to make sense of it.

He couldn't tell if the kid was serious or trying to be cute. And if it was cute, was it cute cute or insulting cute? Magnus couldn't let it be either. The kid's pale eyes just looked at Magnus, and his voice sounded like it was making an observation, something you couldn't help but agree with.

"I got 450 bucks," Carson went on. "An I'm about outta gas. An half hungry. Bit a gas an a sandwich at Kyle's Corner, that's maybe 25 bucks. An that roan's the only horse in that herd's worth only 425 bucks."

"Four-hundred-and-twenty-five bucks," Magnus said, pronouncing each syllable, the mention of a specific price giving him his voice. "You pulled an empty trailer out here, and you're going to pull an empty trailer back. Waste of gas. Four-hundred-and-twenty-five bucks."

"All right," Carson said. "You think you can get more from someone else, I guess you got the right to try."