The World at War (57 page)

Authors: Richard Holmes

ARTHUR BOTTOMLEY

Trade-union leader and Walthamstow borough councillor

There was a lowering of morale and near panic in

Dover towards the end of the war, but this was understandable: Dover had been bombed and shelled every day for four years. To the rest of the country the war was over, but to Dover and Folkestone and those areas it was not. Dover got a particularly heavy bombardment and I had to go down and explain to them the reason why they were suffering was because the German guns on the French side were so heavily fortified. If the Canadians who were there had made a frontal assault, thousands would have been killed. I'm very glad to say the people in Dover and elsewhere accepted this and I want to pay tribute to the people of Dover and Folkestone – they knew more about the war than any other people in this country, including the fighting men, because they had a battle on their doorstep every day

JOHN ROGAN

Air Navigator, Eighth Air Force, USAAF

The most vivid memory I have of World War Two was not a combat experience. I remember the sights in the Underground in London where many of the children were sleeping against the walls and we were told that some of them had stayed there for periods of weeks and hadn't even gone up to see the sunlight.

LUCY FAITHFULL

There was a small survey done when the war was over in the London area and a number of children who had been evacuated for the duration of the war were seen and assessed and a control group of children who had remained in their own homes in London and had therefore not gone to school, had slept in the Underground with their parents at night, had not had school meals or school milk. These two sets of children were assessed together and as far as it was possible to make the assessment the children who had stayed in their own homes in London with all the apparent disadvantages were taller, were heavier and were emotionally more balanced and happier children than those who had been in billets in the country for the duration of the war away from their homes and families.

MICHAEL FOOT

Aneurin Bevan was always getting into trouble at the Party meetings where the majority supported the leadership of Attlee and [Ernest] Bevin and those who were members of the coalition government. But Aneurin Bevan understood better than most of them – and they were deeply occupied of course in their tasks in the war – he understood the ferment that there was outside. There was deep, widespread radical ferment that was illustrated in the

election victory for the Labour Party in 1945. Bevan had prophesied that victory and was confident it was going to happen when most of the others did not believe it was possible. Indeed, Bevin and Attlee wished to sustain the coalition government after the war and it was largely the awareness of the ferment in the country, and of how radical it was and how Labour could put itself at its head, which Bevan realised, which destroyed the possibility of the continuance of the coalition and gave Labour the chance to get independent power.

RAB BUTLER

In my day education wasn't chartered as being so expensive, but the Beveridge Plan was mentioned in millions, and Churchill got very worried and his two Chancellors of the Exchequer, Sir Kingsley Wood and Sir John Anderson, were equally critical. And that's why the Beveridge Plan was delayed after my bill, that's why education came first.

LUCY FAITHFULL

During the whole of the evacuation period I think that in the field of child care and in the field of family life we learned more than we perhaps would ever have learned otherwise. I think that the great mix-up of different types of people in different areas, town and country to the forefront, underlined a tremendous need in the country overall, and I think therefore that the evacuation was the impetus to social legislation following the war.

CHAPTER 23

OCCUPATION AND RESISTANCE

The episode

Occupation: Holland 1940–1944

was among the best of the series because, like all good historians and. journalists, its makers let the interviewees tell the story. I have combined their excellent research with material collected but not used in the earlier episode

Inside the Reich: Germany 1940–1944,

which hardly deals with Germany at all – it is mainly about Stalingrad, perhaps because the episode on Stalingrad eschewed interviews altogether. This was unfortunate, because the question of German resistance to Hitler's malignant regime is one that has yet to be fully integrated into our understanding of the war. Although at first Hitler's undoubted popularity was the principal obstacle to any attempt to remove him from power, there can be no doubt that Franco-British appeasement followed by the ineffectual Phoney War and the collapse of France made him seem magical. Later, the policy of unconditional surrender announced at Casablanca made even officers who hated all he stood for shrink from overthrowing him.

There was another even more discreditable theme. It began with the kidnapping in November 1939 of two British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) officers at Venlo, near the Dutch–German border, where they had been lured by SS Colonel Walter Schellenberg posing as a disaffected Army officer. The two officers had with them a list of all SIS agents in Germany, who were rounded up. From this, in part, stemmed Allied refusal to credit all subsequent approaches by the German Resistance. Secondly, thanks to failures by Special Operations Executive (SOE) desk officers, German counter-intelligence was able to play the 'England Game' using captured

Dutch SOE agents to send false messages back to London, which led to the death of fifty-four SOE agents and the dismantling of organised Dutch Resistance. The culpability of the British officers was covered up and the resulting, unjustified, suspicion of the Dutch led to them not being consulted in the planning of the disastrous Arnhem operation (Market Garden) in September 1944.

ALBERT SPEER

Hitler's Armaments Minister

The way I was going along with Hitler is much more complicated. I can't say that it was a direct line. I was realistic about the outcome of war and of the situation and I did think in a realistic way to prevent the worst. But on the other hand Hitler was still there and his ability to mesmerise people I think was also working with me, so my behaviour was in some way schizoid. I didn't behave like a normal man who would have said, 'This man I can't work with any more.' I was working against him, I was plotting many things against him, but after a while I was again with him. It's almost not understandable this behaviour without knowing what power Hitler had over his surroundings.

HERTHA BEESE

Berlin housewife, Social Democrat

I once took in the baby of a school friend, because both parents had been leading Communists and had been taken away. The baby had not been with me for an hour before they arrived to search my fiat, 'Whose baby is this?' I replied honestly that this was my friend's baby who had been arrested as a Communist leader. When the mother sent me clothing for the baby it had become known immediately and my flat was searched again. They asked what was in the parcel and I replied, baby's clothes. Well, they could hardly have taken the baby away from me – what would they have done with it? But maybe years later they would even have done that. Then they left, embarrassed, but warned me they would come back. Who was watching us, informing on us? When I returned from Bernau by bicycle, sure enough the gauleiter arrived only

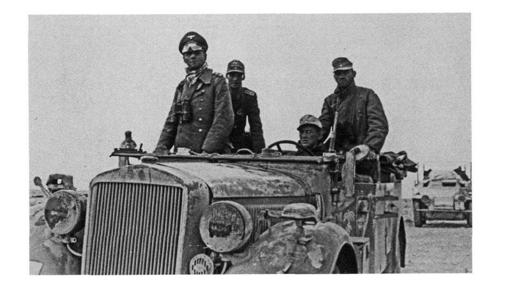

General Erwin Rommel during Auchinleck's Crusader offensive in the Desert War, November 1941.

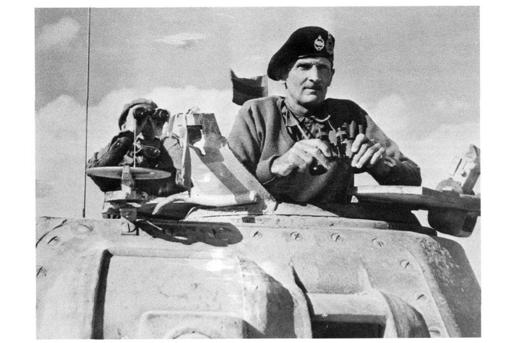

General Bernard Montgomery before El Alamein.

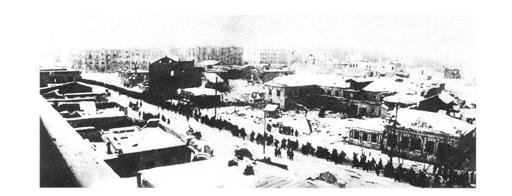

On the Eastern Front. An Arctic convoy, Winter 1941–42.

Panzers cross the steppe, 1942.

Germans are marched into captivity after surrender at Stalingrad. Most of these men would die in captivity.

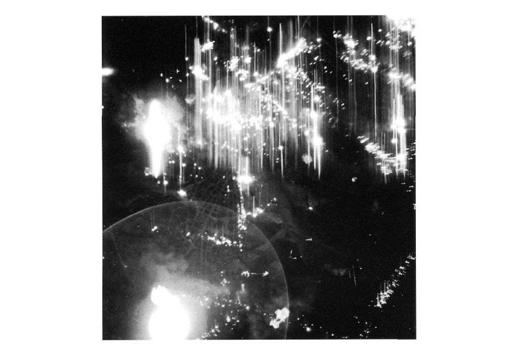

The devastating raids on Hamburg, July 1943. Speer told Hitler that six more such raids would end the war.