The World of Poo (10 page)

Authors: Terry Pratchett

Geoffrey was speechless with delight and awe.

‘It’s not like you to have nothing to say,’ said Grand-mama, chivvying him forward. ‘I must tell you, Sir Harry, Geoffrey has a very keen interest in something dear to your heart, that is to say, muck in all its various ramifications.’

‘Then come and sit beside me, young Geoffrey, and tell me all about it,’ said Sir Harry, in a gruff voice. Sir Harry was a man with daughters and granddaughters, none of whom really wanted to know anything about the source of the family fortune that they enjoyed.

‘Well,’ began Geoffrey, ‘I am very interested in poo and I’ve got this museum in Grand-mama’s garden with thirty-seven different sorts of poo and I’m trying to collect specimens from every animal in the world so that people will come and visit and they’ll be able to see rare and unusual poo.’

‘Well,’ said Sir Harry, ‘I am so pleased to find a young man like you keen to make his way in the world, seeing that so many young men are skivers and slackers. But I have to tell you, Geoffrey, that I’m not sure there’s a living to be made out

of

simply collecting poo samples. I made my money in the bulk market by collecting poo from people who simply wanted to get rid of it – even paid me to take it away – and then selling it on to other people who could find a use for it.’

‘Do you collect from the Royal College of Heralds?’

‘I expect so,’ said Sir Harry, who had an instinct for when a question was more than just a polite enquiry. ‘Was there something in particular you wanted?’

‘Well, I need wyvern poo and hippo poo. Mister Pontoon said that only sirs and lords and nobs can get in there, and sometimes the vet is allowed in when they need help with the wyvern.’

‘I think I can help you there,’ said Sir Harry with a smile. ‘In fact, I have an appointment to visit them this afternoon to discuss my coat of arms. And if your Grand-mama allows it, you could always come with me.’ He winked at Grand-mama.

‘May I go, Grand-mama, may I?’ asked Geoffrey. ‘Please? Please? Please?’

‘If you promise to behave yourself and do what Sir Harry tells you and not bother the staff too much, then I think it would be fine.’

At this point large tureens of soup were brought to the table, shaped very much like outsize chamber pots emblazoned with the guild’s coat of arms. For the first time Geoffrey looked properly around the room. A large sideboard ran along one wall with great silver candlesticks and buckets and strange-shaped bowls and platters laid upon it. More pictures of serious men with forbidding beards lined the wall and there was a list of names painted in gold paint under the heading ‘Presidents of the Guild’.

A magnificent pie, that was served in a very deep dish reminiscent of a bucket, with lots of good gravy, followed the soup. But for Geoffrey the real treat was a huge trifle, just like Cook made, but presented here in a crystal glass dish modelled on one of Sir Charles’s recent creations.

‘Now, Geoffrey, before you go off with Sir Harry,’ Grand-mama warned, ‘I think you ought to visit the cloakroom.’ Geoffrey went in the direction indicated and found a large mahogany door with brass handles and a sign saying ‘Gentlemen’. Inside, shining white tiles covered the walls, floor and ceiling. Geoffrey felt as though he were in a giant upturned sink. A row of hand-basins decorated with flowers ran along one wall, and opposite them stood a row of cubicles. Inside these were water closets grander even than Grand-mama’s, with huge brass cisterns above flowery china bowls and polished copper pipes.

Geoffrey washed his hands with the soap provided, noticing that even that had the guild coat of arms on it, then dried them on the spotless white fluffy towel.

‘That’s a very grand cloakroom,’ he said to Sir Harry as he emerged.

‘I’ll tell you this, young man,’ said Sir Harry. ‘The men who do the dirtiest jobs are always the cleanest whenever that is possible, and it is only right they should have the very best for themselves.’

‘Goodness!’ said Geoffrey. ‘I expect that means that you must have an even grander cloakroom.’

‘Personally, I’m not too worried,’ said Harry, ‘but Lady King has what she calls her en suites and I’m not allowed in the house without walking through a tray of disinfectant. Now, it’s coming up to the time of my appointment at the Royal College of Heralds,’ he said, turning to Grand-mama. ‘I’ll drop your boy home when we’re done, if that’s all right, ma’am. It’s just around the corner from you.’

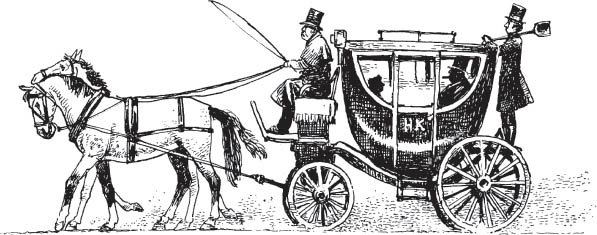

They travelled in Sir Harry’s coach, which was painted a dark and glossy green with the letters H and K in shiny gold leaf on the doors. Fortunately for Geoffrey there was enough ventilation for him to escape the very worst of Harry King’s very large cigar.

2

As they turned the corner by the Palace Sir Harry remarked, ‘See that, Geoffrey? My lads collect not far short of a tonne a week there. Not much paperwork to speak of because his lordship expects his employees to bring their own – and he expects me to do the collecting pro bono.’

‘What does pro bono mean?’ asked Geoffrey.

‘For nothing, lad; free, gratis, goodwill. Still, mustn’t grumble. At least we’ve got a ruler who understands the worth of your working man.’

They had now reached Pseudopolis Yard, and, gesturing towards the Opera House, Sir Harry continued: ‘Even though the performers don’t eat very much, that place gets through so much fizzy wine it’s a golden river in its own right, and that, my boy, is why they call me King of the Golden River.’

‘Sorry, Sir Harry,’ said Geoffrey. ‘I don’t know what you mean.’

Harry King smiled and said, ‘Well, lad, there’s poo, isn’t there? And there’s piss! And, to tell you the truth, I started my career leaving buckets outside every public house for people to piss in, and me and my lads would take them away when they were full. And we would sell it. Amazing stuff. I mean, it’s almost alchemical really. It’s astonishing what you can get out of it, even explosives if you’re careful – but don’t worry about that yourself, of course, it never actually happens while you’re doing it.’

As the journey progressed, every now and then Sir Harry would bang on the roof of the coach with his stick and give the driver instructions to either detour round the back of a building or turn off into an alley and stop near one of his collection points, where he would lean out of the window to make sure everything was in order. He seemed to know everyone by name and his gruff voice cut through the clamour of the street straight into the un-fragrant ears of his employees. ‘Just you clean up that spillage, Jake,’ he shouted to a young man trying to kick

something

into the gutter. ‘That’s money straight down the drain, that is!’

Just as the Royal College of Heralds came into view in the distance, Sir Harry said: ‘And after the piss pots I realized that there was money to be made in the things that people were throwing away. Everything. There’s always someone who could use something, and they have to get it from Harry King.’

They drew up at the large green gates, stepped down from the coach and rang the bell. A small wicket gate in the main door was opened by a liveried porter who asked them their business. ‘I have an appointment with the Herald, smart boy,’ said Sir Harry, taking his cigar out of his mouth. ‘To discuss the progress of my coat of arms.’

‘Which herald would that be?’ asked the doorman, seeming a little unnerved.

‘Search me,’ said Harry. ‘Something like, er, reddish breakfast roll?’

The porter let them into the courtyard and Geoffrey looked around. It was much smaller than he expected, but quite smelly. In the middle was a muddy pond with a couple of hippos wallowing in it, and a small owl was perched on the handle of an old broom leaning against the wall.

‘If you would like to come this way, Sir Harold,’ said the returning porter, ‘we have a design mapped out for your approval. And is there anything we can do to help your young friend?’ he asked, eyeing Geoffrey.

‘Oh, I expect he’ll find something to do around here, he likes the animals,’ said Sir Harry, giving Geoffrey a big wink. ‘Very studious boy, this young lad, very interested in what you gentlemen would call, I suspect, animal excrement.’

‘I’ll let old Joseph keep an eye on the young man. He cleans the yard for us and knows his way around all the pens,’ said the porter, leading Sir Harry away.

A small elderly man, his head bent forward, emerged slowly from a shed and, transferring the owl to his shoulder, took hold of the broom, which he used as a support to walk across the yard. ‘Can I help you clean the animals’ cages?’ asked Geoffrey, seeing a definite poo opportunity.

‘Well, I’ve been round the hippos,’ said the old man, ‘but they’ll probably start again soon. You could give me a hand with the wyvern if you like, he always needs scraping out.’

Geoffrey and the old man walked towards a cage where a miserable-looking creature lay slumped on damp straw. ‘Here, use this,’ said the old man, handing Geoffrey a flat wooden shovel. Just scrape his doings into that bucket there.’