The World's Most Dangerous Place (30 page)

Read The World's Most Dangerous Place Online

Authors: James Fergusson

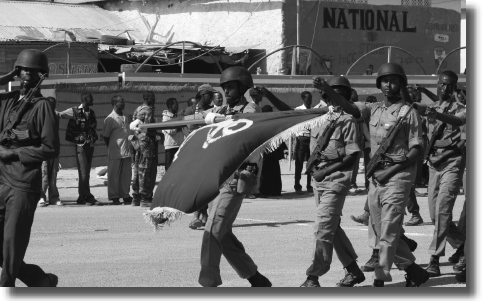

EUNAVFOR, which has a fleet of 25 warships at its disposal (

above

), insists that a sustainable solution will only be found on land. But counter-piracy measures such as the new Puntland Marine Force (

below

) have proved controversial.

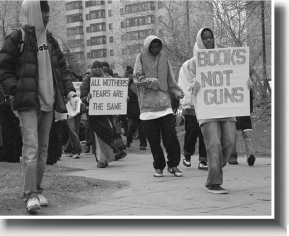

Somali terrorism arrived in the UK with the London Transport attacks of 21/7, 2005: key perpetrators Muktar Said Ibrahim (

above left

), and Somalia-born Ramzi Mohamed during their arrest. Police had earlier filmed their gang on a training exercise in the Lake District (

left

). The reformed jihadist Hanif Qadir (

below

) has made it his mission to dissuade other young Muslims from copying them, through his Active Change Foundation in East London.

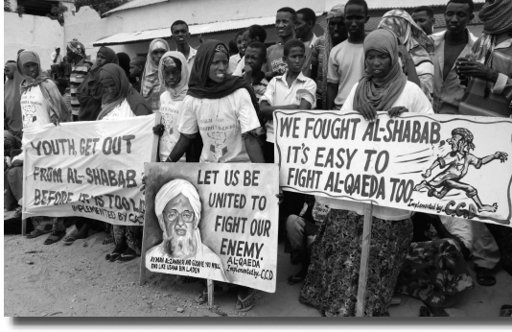

The diaspora have played a key role in resistance to al-Shabaab, as regular demonstrations across the world have shown.

The London Conference of 2012 – the twentieth peace conference since 1991 – was judged a success. But will the international community keep up the pressure on Mogadishu?

*

Although these ransoms sound large, they form only a tiny part of piracy’s overall cost to the global economy. According to Oceans Beyond Piracy, hiked insurance premiums, increased security precautions and the extra fuel needed to re-route cargo ships cost the world $6.9bn in 2011 alone.

*

They were freed three months later in Ximan & Xeeb following a night-time rescue by US Navy SEALs.

*

In recent years religious scholars in several Muslim countries have issued fatwas against the practice that, as some have pointed out, pre-dates Islam by centuries – as the ‘Pharaonic’ description of the procedure suggests.

*

The Johansen family were released, unmolested, in September 2011, following payment of a ransom of between $3m and $4m.

Hargeisa, Somaliland, July 2011

My first visit to Hargeisa, the Somaliland capital, came about by accident when I missed a flight to Nairobi and was forced to wait three days for the next one. The portly Indian pilot at the controls of the tiny UN hopper plane that was supposed to connect with the Kenya flight had touched down so hard on the gravel airstrip at Bossasso that he burst a tyre. There was no spare on board, or at Bossasso airport – which was a Potemkin village kind of place, with a swanky new smoked-glass passenger hall, but no maintenance facilities at all – so we were forced to wait while another plane came out especially from Hargeisa to rescue us.

When the new tyre arrived, there was no jack. The pilots then requested the dozen or so passengers to help them lever one wheel of the first plane up on to a rock. It was 35 degrees in Bossasso, and the passengers were mostly UN office workers in suits. ‘Only in Somalia,’ they muttered under their breath. But no one really minded, because it was better by far than sitting at a desk. UN staffers often

have romantic souls – ‘missionaries, mercenaries or the brokenhearted’, as they like to say about themselves – and there was a definite sense of camaraderie on board when our plane finally reached Hargeisa at sunset, the last possible safe moment for a landing.

Hargeisa was a revelation: a big, bustling African metropolis, the first remotely normal Somali city I had seen. You could understand immediately why so many of Somaliland’s 3.5 million citizens wanted independence so badly, for what had any of the neighbours achieved by comparison since the civil war? In their view they owed their fellow countrymen nothing. Much of their capital had been razed literally to knee-height in 1988 by Siad Barre, whose bombers took off and landed from the airport I had just arrived at, on a plateau above and just next to the city. Tens of thousands were killed. The survivors still spoke of how the surgeons had been forced to operate on the dying while lying down, so continuous was the threat from flying glass and bullets. Hargeisa had been rebuilt since then, and it was impossible not to be impressed by the energy its citizens had put into the task, in which they had received no help at all from central government in Mogadishu. The only visible reminder of the past was a downtown war memorial, a Soviet-era MiG in Somali air force colours that had crashed in the act of strafing the city, now repaired and displayed on a plinth like an overgrown model Airfix.

I made friends with one of the other delayed passengers, a lanky, easy-going Kenyan Somali called Hassan, an AIDS worker who had previously been posted to Hargeisa and knew the city well. The following day we caught a rickety bus – a bus! – which sped us from the airport hotel down the hill into town, the boy conductor flirting with death as he hung by one hand from a rail by the open door. In the city centre was an immense covered street

market, the East African equivalent of a North African souq, bigger by far than any other I had seen in Somalia. We dawdled like tourists in the winding, stall-packed alleys. Here was a shoe stall, the seller half-buried in an avalanche of sandals richly reeking of polish and new leather; there was a sari shop, hung high with bolts of cloth of every hue, like the harem in a folk tale in the

Arabian Nights

. Not for nothing was this region once called the Emporium of East Africa.

Yet Britain’s interest here, unlike that of the Italians to the south, was never precisely colonial. Indeed, British Somaliland was never designated as a colony but as a protectorate, which was only formally established in 1888. The original purpose was to secure a steady supply of meat for the British garrison at Aden in Yemen, a critical but resource-challenged coaling station in the voyage between Europe and India – which was why, until 1899, British Somaliland was administered not from London but from Calcutta, and was nicknamed ‘Aden’s butcher’s shop’.

(In the twenty-first century the export of livestock across the Gulf of Aden continues to boom, although the customers are no longer the British but the Saudis, who are obliged to feed the ever-increasing number of pilgrims who descend on Mecca each year. A record 1.83 million pilgrims completed the Hajj in 2011, a 50 per cent increase over the numbers a decade ago, and they were fed by some of the 4.2 million head of camel, sheep and goats that Hargeisa exports to Arabia each year. With half of its GDP and 70 per cent of its jobs reliant on the livestock business, the economy of modern Somaliland arguably depends like that of no other in the world on the growth of global Islam.

1

)

So many Indian political officers were employed in the protectorate that Captain Malcolm McNeill of the Somaliland Field

Force wrote in 1902 that ‘in this manner, Indian ways and customs (and with them Aden prices) came into vogue in the Somali country, where they have remained until today . . . the coinage is in rupees, and Hindustani being spoken by very many Somalis is practically the official language of the country.’

2