The Year of Disappearances (6 page)

Read The Year of Disappearances Online

Authors: Susan Hubbard

“You never saw Sara do the chart thing before?” Dashay made a face. “She’s always making little maps and such.”

“I need my information to be organized,” Mãe said, still writing.

By nature, her mind wasn’t organized—it enjoyed flitting around too much.

“Next thing she’ll be making PowerPoint presentations at breakfast,” Dashay said. “And that will be the day I move out.”

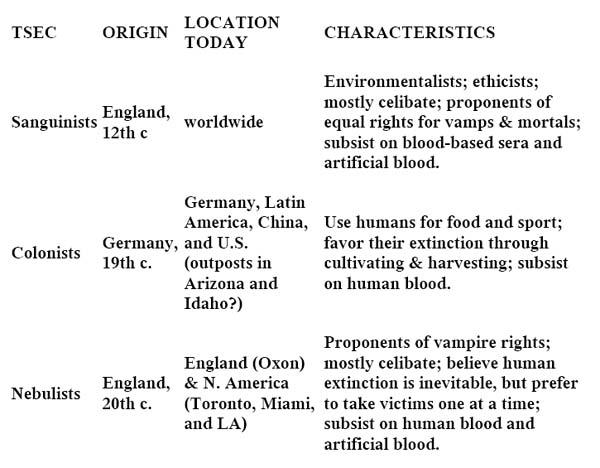

Mãe’s chart looked like this:

I didn’t want to appear ungrateful, but I already knew most of the information. Well, I hadn’t known when the sects had begun or in which parts of the world they were popular, but I’d heard about most of the general preferences.

Mãe heard that thought. “Okay, Ms. Know-it-all. What do most sects have in common?”

I reread the chart, but it didn’t help.

“Come on, Ariella, this is basic stuff. What do most vampires have in common?”

“We have special diets?” I said.

“Yes. What else?”

“We need to be careful about sunlight and fire.” I felt more confident now.

“True. And?”

Dashay was trying not to laugh.

I looked back at the chart. “Um, some of us are celibate. I think.”

“Yes.” Mãe was relieved that the conversation was finally going somewhere. “Sanguinists in particular favor celibacy. Why?”

“Because they think it’s wrong to have sex with mortals?” It was a guess.

“Their tradition says sex is wrong, period,” Dashay said, glancing at my mother to make sure it was all right to butt in.

Mãe said, “Trust you to come in right at this point,” but her voice was amused.

“Remember, the first Sanguinists were priests,” Dashay said. “Maybe that should be listed on this pretty pretty chart.”

My mother ignored her. “Even after they left the church, they favored celibacy. Of course, there were exceptions.”

“Yes, but the girl doesn’t need to know about all of that.” Dashay turned to me. “What you need to think about is this: What do all of these sects have in common besides what you said?”

I reached across the table for a bowl of mixed berries. I felt thoroughly confused.

“They don’t want vampires to breed!” Dashay reached out and brushed Grace, the cat, off the table. “They each have their reasons. Sanguinists think the world is overpopulated, Nebulists think it’s nasty to have sex, and the Colonists want the humans to breed because it means more food. But vampires having children? None of them think it’s the right thing to do.”

“Why not?” I felt insulted, somehow.

Mãe was watching me closely. “If a vampire and a mortal have a child, that child is likely to have health problems,” she said.

Dashay said, “That’s only a part of it. These sects, they think the vampire blood is pure, and the world belongs to those

pure folks.

”

A “half-breed” myself, I made an effort not to take any of this personally. “What about vampires breeding with vampires?”

Dashay shook her head. “Can’t happen.”

“Well, that’s what the lore tells us.” Mãe’s jaw clenched, a sign that she felt worried or sad. “Who knows? There’s been no research to speak of. All we have to go on are gossip, myths and folk tales, Internet chat rooms. Most vampires are like Victorians—they prefer not to talk about sex. Anyway, now you know why there aren’t other teenagers like you in Homosassa. You’re a rare breed, Ariella.”

I felt—here’s that word again—dizzy. The conversation hadn’t convinced me of anything. “Let me see if I understand,” I said. “I shouldn’t ever have a child. Is that what you’re telling me? Because if I fall for a vampire, having children

can’t happen,

and if I fall for a mortal, the child might have

health problems.

”

I wanted to ask questions. How severe were the possible health problems? Was I likely to be sick? I looked down at the well-intentioned chart, and I wished I’d never changed the subject.

Then Dashay picked up a pencil. Mãe winced, but didn’t stop her. Dashay added another sect at the bottom of the chart: US. In the ORIGIN column, she wrote WHO KNOWS, and under LOCATION, she wrote SASSA. And for CHARACTERISTICS, she put a large question mark.

“

We

are not part of any sect,” she said. “And what we do, whatever characterizes us—that remains to be seen.”

I reached over and nudged Grace off the table again, thinking hard. For my father, being a vampire seemed such a complicated business, bound up in duties and ethics and obligations of all sorts. For my mother and Dashay, it wasn’t such a big deal. And for me?

Something else the sects have in common: they all keep their distance from humans. Even the Sanguinists, who believe in peaceful coexistence, don’t mingle much with mortals.

“I have a question,” I said. “Why don’t we tell people what we are? Why do we go to Flo’s and not to Murray’s? Why aren’t we out in the open?”

“Because exposure can be dangerous.” My mother spoke slowly, patiently, but she was surprised by the naïveté of my question.

“Some vamps are out of the box,” Dashay said. “Mostly in the entertainment business. You can be a rock star or an actor and say you’re a vamp, and the mortals think, ‘Yeah, right.’ They don’t feel threatened by that, for some reason.”

“Because they think it’s a pose. And they tell themselves that there’s no such thing as vampirism.” Mãe pushed her hair back from her forehead.

I remembered the line from

Dracula

(we call the 1931 version simply “The Movie”): “The strength of the vampire is that people will not believe in him.”

“If they don’t believe, then where’s the harm in calling yourself a vampire?”

Dashay shook her head at me, as if I were being deliberately obtuse. “Because we have been known to bite.”

“

We

try not to.” My mother’s voice tried to soothe me. “But the Nebulists have no qualms about biting. They seem to get away with it, by and large—if incidents come to light, mortals are usually blamed. The Colonists prefer to kill in batches—they say it’s more efficient, even claim it’s more

humane.

”

“Has my father ever bitten anyone?” I’d wanted to know that for years.

“Not to my knowledge,” Mãe said. “It would go against all his principles.”

“Well, he had to bite the man who vamped him—otherwise Raphael wouldn’t be a vamp.” Dashay lifted Grace and set her outside the kitchen, shutting the door.

Mãe and I exchanged a look, and a name:

Malcolm,

the name of my father’s old friend, who had turned on him, made him a vampire against his will. Malcolm had vamped my mother, too, after I was born.

“Do we need to keep on talking?” Dashay yawned. “I want to wash my hair.”

“Have we answered all your questions?” Mãe asked.

I swallowed a mouthful of berries without tasting them. I said I supposed so.

“Wait,” Dashay said. “The reason we don’t go to Murray’s? It’s too bright in there. Those fluorescent lights make me batty. Plus, they don’t serve Picardo, and they have a terrible cook.”

Later, when we were alone, Mãe told me she’d driven by Bennett’s house that morning and seen a

FOR SALE

sign on its lawn.

“Oh, rats,” I said. We were working in the herb garden, and I stopped weeding. “Have you told Dashay?”

“Not yet.”

“You have to tell her. And it will break her heart all over again.”

“Tell her what?” Dashay leaned out of her bedroom window, her hair wrapped in a towel. Then she heard what we were thinking. We didn’t have to say a word.

My mother and Dashay made a date with Bennett’s real estate agent to see the house later that night. They pretended that they wanted to buy it.

“Why not be honest?” I asked. “Tell her that you want to find Bennett.”

Dashay refused, and Mãe agreed with her. “This is the best way,” Mãe said. “Ariella, are you packed yet?”

We were leaving for Saratoga Springs the next day.

“I need my metamaterial suit,” I said.

“No, you don’t.” She didn’t like the suit, which my father had given me in order to let me turn fully invisible. “I don’t know where it is, and in any case, we’re going to be visible on this trip.”

That meant I’d be packing jeans and T-shirts. “Whatever,” I said.

They both looked shocked. “I’m sorry,” I said. “I’ll pack.”

Mãe said, “Don’t forget to bring a dress. We’ll go out to dinner, you know.” She liked to dress up and go to fancy restaurants.

Left on my own after dinner, I turned on my laptop and decided to try to answer some questions by myself.

It took a while, but after reading more than a hundred posts by strangers, I arrived at the definitive reason why vampires and mortals tend not to mix: lack of trust.

Vampires lie. They lie to mortals almost all the time, by hiding their identity. And they lie to each other for all sorts of reasons. When a vampire blocks her thoughts, she may be lying—or she may want you to think she’s lying, which is a more sophisticated tactic.

Of course mortals lie as well. But because we can hear their thoughts (not to mention hypnotize, scare, and bite them), we have a decisive strategic advantage.

Could vampires and humans ever really coexist in the peaceful, productive way envisioned by the Sanguinists? I began to doubt it. Could vampires lead ethical lives if they couldn’t be trusted? Weren’t honesty and trustworthiness essential to ethics?

If my father had been there, we would have talked for hours about those questions, considering an array of interpretations and implications, redefining terms, using language to link the objective, social, and subjective worlds. But he wasn’t there, and the questions remained a muddle to me.

When my cell phone rang, I was happy to stop thinking. Mysty’s voice, breathier and higher-pitched than mine, informed me that she had a date tonight with Jesse.

I knew she wanted my approval. “That’s good,” I said. “Really good. Great.”

“We’re going down to the dock to, um,

stargaze.

”

“It’s a good night for it,” I said. “A full moon, and Mars will be rising in the east.”

She giggled, as if

stargaze

meant something else. In terms of talking to a friend, I was out of practice.

“I’ll be sure to ask Jesse about Mars,” she said. “I hope the bugs aren’t bad. Mosquitoes love me.”

I thought about recommending herbs that repel mosquitoes. My mother grew some. Then I realized that she didn’t want advice. She wanted sympathy.

Have you ever analyzed human conversation? Most of it lacks purpose in the sense of accomplishing a task or seeking information. Most of it attempts to establish a personal relationship based on mutual agreement. I knew this from conversations with my friend Kathleen, who, for a while, had called me almost every night.

“Mosquitoes,” I said now. “Yuck.” Mosquitoes don’t bother vampires. I guess our blood isn’t to their taste.

“I hate mosquitoes.” Mysty’s voice had a faint Southern drawl, softer than Autumn’s Florida accent. “I hate birds, too.”

“Why do you hate birds?”

“I’m afraid of them. They have such mean little faces.” Mysty made a funny sound, a kind of guttural chirp, like the noise cats make when they’re unsettled. “They look like they want to peck out your eyes.”

I couldn’t think of anything to say.

“What are

you

afraid of?” she asked me.

“Being left out.” I said it without thinking.

“Oh, don’t you worry about that.” She sounded amused. “I’ll make sure you’re part of all our parties. And when we start school again, I’ll introduce you around.”

“I don’t think I’m going to school,” I said. It hadn’t even been discussed.