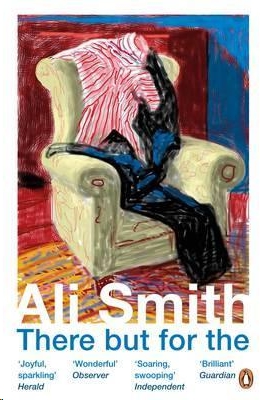

There but for The

Authors: Ali Smith

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2011 by Ali Smith

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Originally published in Great Britain by Hamish Hamilton, published by the Penguin Group, an imprint of Penguin Books Ltd., London.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Nanada Music, B.V., c/o Tier Three Music (ASCAP) for permission to reprint an excerpt from “Ding-A-Dong” by Dick Bakker, Will Luikinga, and Eddy Ouwens, copyright © Nada International C.V., administered by Nanada Music, B.V. International copyright secured. All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Smith, Ali.

There but for the / Ali Smith.

p. cm.

eISBN 978-0-307-37998-6

1. Middle-aged men—Fiction. 2. Personal space—Fiction.

3. Social interaction—Fiction. 4. Dinners and dining—Fiction.

5. Greenwich (London, England). 6. Identity (Psychology)—Fiction.

7. Psychological fiction. I. Title.

PR6069.M4213T47 2011 823'.914—dc22 2010051377

Cover design by Peter Mendelsund

First United States Edition

v3.1

Contents

The fact is

THERE

There was once

BUT

But (my dear Mark)

FOR

For 29 January

THE

for Jackie Kay

for Sarah Pickstone

for Sarah Wood

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

AND

THANKS

I’m indebted for sources of some of the stories about songs in this book to

America’s Songs

by Philip Furia and Michael Lasser (Routledge, 2006). I’m also indebted for information used in the first section to Caroline Moorehead’s

Human Cargo: A Journey Among Refugees

(Chatto and Windus, 2005).

Thank you, Cherry. Thank you, Lucy.

Thank you, Xandra, and thank you, Becky.

Thank you, Sarah and Laurie.

Thank you, Mary.

Thank you, Kasia.

Thank you, Andrew, and thank you, Tracy, and everybody at Wylie’s.

Thank you, Simon.

Very special thanks to Kate Thomson.

Thank you, Jackie.

Thank you, Sarah.

The essence of being human is that one does not seek perfection, that one is sometimes willing to commit sins for the sake of loyalty, that one does not push asceticism to the point where it makes friendly intercourse impossible, and that one is prepared in the end to be defeated and broken up by life, which is the inevitable price of fastening one’s love upon other human individuals.

—George Orwell

For only he who lives his life as a mystery is truly alive.

—Stefan Zweig

I hate mystery.

—Katherine Mansfield

Of longitudes, what other way have we,

But to mark when and where the dark eclipses be?

—John Donne

Every wink of an eye some new grace will be born.

—William Shakespeare

The fact is, imagine a man sitting on an exercise bike in a spare room. He’s a pretty ordinary man except that across his eyes and also across his mouth it looks like he’s wearing letterbox flaps. Look closer and his eyes and mouth are both separately covered by little grey rectangles. They’re like the censorship strips that newspapers and magazines would put across people’s eyes in the old days before they could digitally fuzz up or pixellate a face to block the identity of the person whose face it is.

Sometimes these strips, or bars, or boxes, would also be put across parts of the body which people weren’t supposed to see, as a protective measure for the viewing public. Mostly they were supposed to protect the identity of the person in the picture from being ascertained. But really what they did was make a picture look like something underhand, or seedy, or dodgy, or worse, had happened; they were like a proof of something unspeakable.

When this man on the bike moves his head the little bars move with him like the blinkers on a horse move when the horse moves its head.

Standing next to the sitting man so that their heads are level is a small boy. The boy is working at the grey bar over the man’s eyes with a dinner knife.

Ow, the man says.

Doing my best, the boy says.

He is about ten years old. His fringe is long, he is quite long-haired. He is wearing flared jeans embroidered in yellow and purple at the waistband and a blue and red T-shirt with a Snoopy on the front. He forces the thing off the man’s eyes so that it flicks off and up into the air almost comically and hits the floor with a metallic clatter.

This T-shirt is the first thing the man on the bike sees.

The Snoopy on it is standing on his hind legs and wearing a rosette on his chest. The rosette says the word hero on it. Above the Snoopy there are more words, in yellow and in the writing that’s always used with the Snoopy characters. They say: it’s hero time.

I’d totally forgotten about that T-shirt, is the first thing the man says as soon as the boy’s jemmied off the thing that’s been over his mouth.

Yeah, this one’s good. But you know the orange one that says hug a beagle on it? the boy says.

The man nods.

Whenever I wear it, it’s weird, but girls are always really nice to me, the boy says.

The man laughs a yes. He looks down at his feet, where both the grey rectangles landed. He picks one of them up. He weighs it in his hand. He feels the tender places round his eyes and at the edges of his mouth. He drops it on to the floor again and holds his hand away from himself in the air and flexes it. He looks at the boy’s hands.

I’d forgotten what my own hands looked like, he says. Look like.

Okay, so we’ve done that now. So

now

can I show you? the boy says, do you want to know

now

?

The man nods yes.

Good, the boy says. Okay.

He takes two blank pieces of paper off the floor. He gives one to the man. He sits on the bed and holds the other piece of paper up.

So, he says. What you do is. You get a plain A4 sheet of paper and then you fold it in half. No, that way. Lengthways. And make sure the corners are even, so they’re on top exactly.

Okay, the man says.

Then unfold it so it’s like a book, the boy says.

Okay, the man says.

Then fold one corner, the boy says, the top corner, then fold the other. So it looks like that, like a book but a book with a triangular head. Then fold the folded point towards you down and crease. So it looks like an envelope. Then fold over one corner again so there’s a little tab sticking out at the end. Then the same for the other one. But so that you get a blunt point, not a pointed point. Blunter is better.

Wait, wait, wait, the man says. Hang on.

Yes, a little triangle sticking out of the flap, the boy says. Then fold the small triangle back up on top of the flaps. Then fold outwards, not inwards, so that the triangle is on the outside. Make sure it’s all even. Then take hold of the top and fold it down to make the first wing. Then flip over and do the same for the other wing. Make sure it’s even or it’ll be out of control.

The man looks at the plane in his hands. He creases it down, then opens it up. Outside, on its top, it looks like a plain folded piece of paper. Inside, underneath, it is packed tight into itself with surprising neatness like origami, like a small machine.