These Delights

Authors: Sara Seale

THESE DELIGHTS

by

Sara Seale

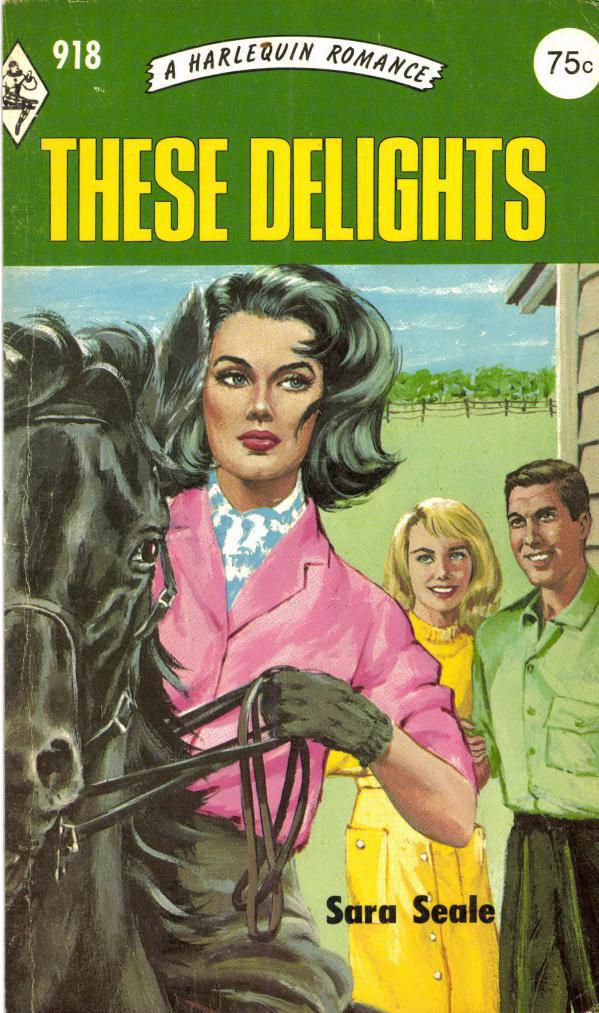

Luke Merrit’s engagement to Diana was presenting him with some problems, not the least of them being how to retain his independence in the face of his wealthy

fiancée’s

well-meant but unthinking interference.

And when three young cousins—Lou, Pauline, and the warmhearted, impetuous Vicky

—

arrived on his Devon farm as unexpected guests for the summer, they did nothing to improve the situation.

CHAPTER ONE

The black gelding moved down the steep hill from the moor with a mincing gait, distending his nostrils and sidling away from the shadows of the high banks in the sharp May sunshine. The girl who rode him spoke soothing words, calling him “my lover” in the west-country way, and her hair, loose on her shoulders, was as dark as the horse’s fine mane. Ahead, the road wound upwards again back to the moor, and in the coombe, Monksbridge village lay between the two hills, a straggle of thatch and old grey stone and the pink wash which, at sunset, threw back a rosy glow.

She had known the village since she was a child; Mrs. Smale, whose sweet-shop had once held such glories, Bidder the butcher, who wore a straw hat summer and winter, and Pengelly the little dwarf, who kept the saddler’s shop and did the best repairs in Devon. He was standing in the door of his shop now, and called out: “

‘Mornin’, Miss Sales,” but Bidder, who had known her longer, shouted: “How be doing Miss Diana?” and waved his long knife at her.

She smiled a greeting to both and rode on through the village and over the old hump-back bridge, making for Monk’s Farm at the top of the other hill, and the spaniel running at the horses’ heels, shook his long ears and made a snap at a sleeping cat.

As she rode, slackening her reins for the steep pull of the hill, Diana thought with pleasure of Luke and the farm and all that she would do for them both when they were married. The Merrits, brother and sister, were not poor by village standards, but neither were they well-off by the standards of the Manor, and there was no denying that the handsome marriage settlement she would bring with her would put the farm on its feet. Already she had planned what to do with the old shippon and worked out the cost of a new

modern

dairy. The house, too, could be charming.

What money Luke could spare had gone into the farm and the house was shabby and needed alteration. She would sweep away all that old-fashioned furniture and beg pieces from the Manor to bring beauty to the rooms, and Luke

himself

should come out of his rut and learn to make useful friends and contacts. Dear Luke, she thought, turning in at the white farm gates and putting her horse into a gentle canter on the deep grass verge; funny old stick-in-the mud, with his la

ck

of ambition, his queer values and thorny principles.

As she neared the house, she saw that he was standing in the yard, watching her, and she raised a hand in quick salute. She experienced, as she sometimes did at unexpected moments, that odd impression that he was still a stranger, watching her so quietly with abstracted grey eyes, and thought that at times he looked older than his thirty-five years, with his lined forehead and the little crinkles at the corners of his eyes. Then his lean brown face lit up with its charming, slightly crooked smile, his eyes lost their abstraction, and he was again as she thought of him, familiar, admiring, and a little

la

zy.

“How nice,” he said, a hand on her horse’s bridle, “and how very well you look.”

“You only saw me two days ago,” she laughed.

He smiled again.

“So I did. But you look different, somehow. I think it’s your hair.”

“Oh, that!” She pushed it

back

with an impatient hand. “I lost my hair-net on an overhanging branch. I expect I look a sight.”

“I like it like that, loose and a

little

dishevelled. Why don’t you wear it that way, sometimes?”

“I like neat hair,” she said a little impatiently. “And so do most men.”

“Do they?” He looked amused. “I must confess to liking my girls a bit tousled at times.”

She made a face and swung herself out of the saddle with easy grace.

“Well, I’m not the tousled type,” she said a little shortly.

“What a pity,” he remarked, and led her horse into the stable.

She followed him, a little pu

zzl

ed by his manner. She felt untidy and at a disadvantage and she stood in the deep straw of the loose-box, watching him unsaddle her horse, and wondered what he was really thinking. The small task finished, he came and put a hand under her chin, looking into her flushed face.

She was a tall girl and

he

did not have to stoop very much as she raised her face. She drew back a little as he kissed her. She disliked all physical contact, and her engagement to him had been pleasant because he so seldom made love to her. But today there was something different about him, and even as she resisted him she felt she must apologize.

“I’m sorry,” she said a little breathlessly. “You know I don’t like being touched.”

“Even by me?”

“

Well—no—not quite in the same way of course.”

“

That’s just as well,” he retorted a little wryly. “Marriage is hardly an untouchable state.”

“That’s different,” she said, but even to him she could not explain what she meant. Marriage, one knew, held obligations. One honored those obligations because one was left with mutual respect and affection, like one’s parents.

He was watching her while she thought these things and his eyes were land but a little puzzled.

“Very different, I imagine,” he said with a little laugh and let her go. “Stroll round the farm with me for half an hour. You’ll stay to lunch, of course.”

They walked to the low boundary wall which marked the limit of Luke’s land. From here the moor rose steeply from fields to horizon, with Monkstor a rugged pile of boulders in the distance. The spring swayling had not touched this stretch of moor, and the gorse was in full flower.

They sat on the wall, smoking cigarettes, the sun warm on their backs, and the spaniel threw himself down, panting in the grass. Diana put out an eager hand.

“Luke, I wish you’d let me start on the shippon now,” she said.

“There’s so much to be done. Why need we wait?”

He glanced at her a little curiously.

“The waiting is entirely up to you,” he said.

She tossed a teasing strand of hair out of her eyes.

“Oh, I didn’t mean marriage,” she said. “Why must we wait for that? We could be getting on with jobs now, and then there would be so much less to do, and I could concentrate on the house.”

“I’m sorry, my dear, but you remember that was the one stipulation I made.”

“But why—why? What difference does it make? It’s the same money in the end.”

He smiled.

“That’s not the point. I dislike the idea of your money paying for all this anyhow, but once you’re my wife, things will at least be on a different footing.”

She moved impatiently.

“I never can see it. Unless you think perhaps that engagements can be broken and then it might be rather awkward.”

He raised an eyebrow.

“Well, it’s always a possibility, isn’t it? And think how embarrassed I should feel if you had put a great deal of money into the place.”

“That’s ridiculous! Unless, of course, you jilted me for some dizzy blonde.” She tried to laugh, but she felt uncomfortable, not sure whether he was serious or not.

“Silly cuckoo!” His voice was teasing. “I think it’s much more likely that you’ll throw me over for someone your parents would consider far more suitable. But in any case, darling, there’s no need to wait. Why not marry me qui

c

kly, then you can start all your expensive, and, to my way of thinking, unnecessary schemes at once.”

She seized immediately on the matter which was most important to her.

“You might see it my way, and you shouldn’t think my plans are unnecessary,” she said vehemently.

“

You have no ambition, Luke. You’re quite content to muddle along on old-fashioned methods and never dream of trying to get the best out of the farm.”

He sounded amused as he replied.

“We’re not very go-ahead, certainly, but I’ve great faith in Tom Bowden. We manage to get a living from the place.”

“Oh, Bowden!” She was irritated. “He’s very sound in his way, but he’s like most Devon farmers, years behind the times. You leave too much to him. If you

must

have a working foreman, why don’t you get a younger

man

with an agricultural degree behind him and a proper scientific training?”

“

Tom’s just as capable of running the place as I am,” he said mildly. Her assurance on these matters amused

him, b

ut he had no intention of sacrificing Tom Bowden to some young college graduate with no working experience. “No, Diana, you must take us as you find us at Monk’s

F

arm,

and I hope you won’t be too drastic with all your improvements.

”

“But can’t you

see

what I’m trying to do? Can’t you appreciate, even if you are unambitious—oh, you’re just laughing at me!”

She had turned to face him, and her exasperated expression altered reluctantly to one of rather charming sheepishness. He took her face between his hands, studying the pure oval of its outline, the straight little nose, the mouth that was a thought too small and too determined, but entirely redeemed by the fine, dark eyes, and kissed her very gently. This time she did not pull away, but allowed her lips to remain passive under his, feeling her engagement ring cutting into her finger as she pressed both hands against the wall.

“Why do we wait?” he said again. She drew back then and tri

e

d to tidy her hair.

“Oh, Luke, we went into all that four months ago,” she said. “You know Mother doesn’t want us to be in a hurry for one thing and I—well I want to get to know

y

ou first.”

He looked surprised.

“Don’t you know me? We’ve been neighbors for about twelve years.”

“But that doesn’t count. I was at school, and then I was in London for some years. Besides, our families never really knew each other well.”

No, he reflected, that was certainly true. He and Hester had had little in common with the Sales until Diana had so unaccountably taken a fancy to them, or perhaps to the farm.

“But there’s no reason why,

”

she resumed, returning to the attack with that single-mindedness which both impressed and exasperated him, “we shouldn’t start alterations and improvements. The sooner we start the better, and it’s absurd to waste months with nothing done.”

He threw away his cigarette-end and stamped it out in the grass.

“I’m sorry, Diana,” he said gently. “It may seem unreasonable to you, but that’s my decision. When we’re married you can have a free hand, providing you don’t upset Tom too much, but until then—well, you’ll have to be content with planning, darling. It must be nearly lunch-time. Shall we go?”

Corky, Luke’s little Cockney man-of-all-work, who managed the work of the house with astonishing efficiency, was just going to ring the outside bell, and his melancholy monkey face broke into an uncertain grin at sight of Diana. “ ‘Morning, miss,” he said. “One extra for lunch, sir?”

“Please, Corky. It won’t throw your arrangements out, I hope.”

“Not so you’d notice it, sir. It’s fish pie and apple pud.”

They went into the dim, raftered hall, with its big stone flags and scent of burning applewood. Another window could easily be cut in the south wall, giving it more light, thought Diana, preceding Luke into the shabby, comfortable living-room where Hester Merrit sat at her desk, finishing accounts.