Think Like an Egyptian (11 page)

Read Think Like an Egyptian Online

Authors: Barry Kemp

20.

PIG

Certain cultures develop strong predjudices against foods that others find fully acceptable. Judaism and Islam (but not Christianity even in its Middle Eastern forms) have categorized the pig as an unclean animal not to be touched or eaten. Herodotus reported in the 5th century BC that the Egyptians considered the pig to be unclean yet maintained herds of them and sacrified them on a particular festival. This ambiguity matches the evidence from earlier periods.

It seems that Egyptians were not prohibited from eating pig but felt a degree of reservation. Studies of animal bones recovered during the excavation of ancient Egyptian settlements show that the pig was common. Many of the bones bear both cut and chop marks from butchery. There are occasional pictures in tombs showing herds of pigs. An 18th Dynasty mayor of El-Kab recorded in his tomb his ownership of 1,500 pigs (along with 122 cattle, 100 sheep, and 1,200 goats). More remarkable is a pious donation to the temple of Ptah at Memphis of 2,000 pigs. Pork did not feature in religious offerings, but then neither did sheep or fish; beef and goose were what the spirits of the gods and of the dead preferred.

21.

SETH-ANIMAL

In Egyptian mythology, Seth was the wicked rival of his brother Horus, both sons of the murdered King Osiris. Horus, the rightful claimant to the throne of Egypt, was the mythical embodiment of a loyal son, whereas Seth, who disputed Horus’s claim to the throne, was simultaneously held responsible for the murder of their father. Seth’s hieroglyph depicts him as an animal, a quadruped not easily identified with an actual animal species.

The god Seth was a complex figure in Egyptian thinking who defies simple definition. Occasionally the myth referred to Seth as Osiris’s brother (and thus Horus’s uncle): his identity varied and mutated in much the same way as his symbolic significance. He symbolized a frequently dangerous “alternative,” against which positive characteristics could be defined. One text described him as the “oldest magician of the sacred place of the first occasion” (the time of creation).

Unlike Satan in the Christian worldview, Seth was not portrayed as a devil beyond redemption. In the end Seth submitted to the judgment of the high court of gods, was reconciled to Horus, and settled for second place in the kingdom. In this context he became a legitimate patron god and supporter of Egyptian kingship. Two kings of the 19th Dynasty, Seti I and II, even named themselves after him, although his name still carried an ambiguous and powerful meaning. When Seti I built a temple to Osiris on a particularly lavish scale at Abydos, the artists decorating the temple chose a tactful spelling of the king’s name that omitted the hieroglyph of his archrival Seth.

Certain qualities of Seth were also believed to be embodied within the Egyptian people; we know this from a book belonging to an ancient Egyptian scribe. Scribes—civil servants of their day—accumulated private libraries of papyri covering diverse subjects. One such library, owned by a succession of scribes from the village of craftsmen at Thebes (Deir el-Medina), included a book on how to interpret dreams. Before interpreting the dream of a client, it was necessary to place that person in a particular group, perhaps comparable to modern horoscope groupings. A surviving fragment of the papyrus lists the characteristics of a person with “Seth” qualities: he has red hair, drinks beer and becomes aggressive, attracts women with his passion, and fights murderously with weapons. In spite of this he can be long-lived, reaching 84 years, and he is not an outsider. He can remember his dreams, and according to the details they can be interpreted as either a good or bad omen.

Seth was an essential role model who helped to explain the turmoil and divisions of the world. His hieroglyph is found attached to words for “storm,” “tumult,” “illness,” and “nightmare.” In another pairing he represents the lands beyond the Nile Valley—especially the desert—and by extension is a god of foreign places, particularly those of the Near East. In 1258 BC King Rameses II made a peace treaty with the king of Egypt’s long-term enemy, the kingdom of Hatti (home of the Hittites). Both the Egyptian and the Hittite versions of the treaty have survived. Each places the treaty under the care of their gods. In the Egyptian version, however, the Hittite gods are represented as local variants of Seth. The belief in Seth illustrates how ancient Egyptian thinking at a serious level differed from our own: whereas modern learning tends to seek logical explanations for the world around us that feed into a single grand scheme, Egyptian logic and meaning could shift depending on the immediate context.

22.

RED

The hieroglyph for red depicts a flamingo, which until about a hundred years ago was still breeding in the Nile Delta. To modern eyes the flamingo, which is white and pink, is a poor representative of redness, yet it made sense in the Egyptian’s world. Not much else had a naturally red tone, and it has a distinctive enough outline for a hieroglyph. When Egyptians created hieroglyphic signs to write on walls of tombs and temples, they were attracted to bold clear shapes that instantly conveyed the essence of the object. If necessary (for example, no. 23, “Sparrow”), one component part (in that case the sparrow’s tail) is rotated through 90 degrees to present a more characteristic outline.

We can never know which came first, the word for red—then used to describe the flamingo—or the name of the flamingo, which then created a word for red. The separate naming of fine color distinctions is a relatively modern phenomenon. The Egyptians managed with very few color terms, and these covered a wide range of tonality. They had opportunities to see the color orange, in deposits of desert sand or in the sky at sunset, but not only did they have no reason to single it out for comment, in lacking oranges they had no convenient reference color. Red could describe both the pinkness of a flamingo or the color of blood. When paired with another hieroglyph to create the word “red land” (another word for desert), we learn that red also included what we see as oranges, grays, and yellows.

In some contexts, red could stand for “otherness,” rather in the way that Seth did, which explains why Egyptians with red hair were associated with Seth. A word derived from “red” meant “wrath,” as did the phrases “red of heart” and “red of face.” Red was the color of enemies. One inexpensive way of safeguarding Egypt from attack was to write the names of hostile foreign leaders in red ink on clay figurines or pottery vessels and then bury or smash them. The gods would do the rest.

Not all red things were bad. Red ink was used to highlight significant words in texts without any negative implications, and the Red Crown was worn by the king to symbolize his rule over Lower Egypt, standing in contrast to the White Crown of Upper Egypt. Red was a common color used to paint doors, window shutters, and wooden columns in houses, presumably as a simple way to provide a contrast with the bare mud-plastered walls, which would not always have been whitewashed.

Red pigment was easy to acquire. It came as ocher from the desert and could be made into a powder so fine it could permanently color linen cloth, although by the 18th Dynasty the Egyptians were also dyeing cloth with madder, a red vegetable dye. In paintings, a darkish red was the preferred color of male skin. The fact that it contrasted with the yellow skin color for women and was used for field laborers and for officials alike is probably a sign that it stood for the positive values of maleness, since artists were themselves men.

23.

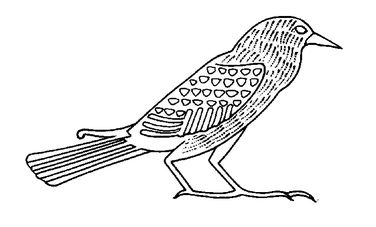

SPARROW

A small brown bird, probably a sparrow, acts as the sign denoting things of ill-omen. There is nothing in written sources to suggest that small brown birds were in themselves thought to be evil or unlucky. They are in fact rarely mentioned. The sparrow hieroglyph most likely developed its meaning because it represented the least favored of a set (in this case of birds), and it was common. In an opportunistic way this tradition became embedded in the hieroglyphic script. Words that take this determinative sign include “small,” “empty,” “narrow,” “bad,” “to be ill,” “misery,” “injury,” “to sigh,” “ruin,” “misfortune,” “to fail,” “deprivation,” and even “evil” and “wrongdoing.”

24.

GOOD

Whereas the Egyptians had a rich vocabulary for unpleasantness, they relied heavily on a single word, “good”

(nfr),

for positive appreciation across a broad range of experience. Unlike the word for misfortune, which Egyptians associated with the sparrow, the symbol for good was not taken from the natural world by direct association. To write it they chose a sign that represented something quite unrelated (the heart and windpipe) which happened to possess the same sequence of consonants n

+ f +

r. This was the standard alternative way by which hieroglyphs were selected to form part of the writing system. Once an Egyptian made the connection while learning hieroglyphs, the sign for heart and windpipe would, of course, read immediately as “good” and so would, in effect, become its symbol.

(nfr),

for positive appreciation across a broad range of experience. Unlike the word for misfortune, which Egyptians associated with the sparrow, the symbol for good was not taken from the natural world by direct association. To write it they chose a sign that represented something quite unrelated (the heart and windpipe) which happened to possess the same sequence of consonants n

+ f +

r. This was the standard alternative way by which hieroglyphs were selected to form part of the writing system. Once an Egyptian made the connection while learning hieroglyphs, the sign for heart and windpipe would, of course, read immediately as “good” and so would, in effect, become its symbol.

Nfr

was applied to the fineness of linen, the quality of a wine (which, when particularly good, was

nfr nfr).

nfr nfr).

The king was “the good god,” one’s pet name among friends was one’s “good name,” and the holiday feeling was captured by the expression “making a good day.” It also applied to provocatively attractive young women: In one story, King Sneferu, father of Khufu the builder of the Great Pyramid, takes pleasure in a boating party in which he is rowed up and down by 20 beautiful girls (“girls” is a noun derived from

nfr

) whose beauty lies in “their limbs, their breasts, and their braids” and the fact that they have not yet given birth, and who are to entertain the jaded king by wearing open bead-latticed garments instead of their normal clothes. When one of them grows petulant at having dropped a turquoise pendant overboard, a magician folds the waters back so that it can be retrieved.

was applied to the fineness of linen, the quality of a wine (which, when particularly good, was

nfr nfr).

nfr nfr).The king was “the good god,” one’s pet name among friends was one’s “good name,” and the holiday feeling was captured by the expression “making a good day.” It also applied to provocatively attractive young women: In one story, King Sneferu, father of Khufu the builder of the Great Pyramid, takes pleasure in a boating party in which he is rowed up and down by 20 beautiful girls (“girls” is a noun derived from

nfr

) whose beauty lies in “their limbs, their breasts, and their braids” and the fact that they have not yet given birth, and who are to entertain the jaded king by wearing open bead-latticed garments instead of their normal clothes. When one of them grows petulant at having dropped a turquoise pendant overboard, a magician folds the waters back so that it can be retrieved.

Other books

Kissing Comfort by Jo Goodman

Sherwood Nation by Benjamin Parzybok

Linda Castle by Territorial Bride

My Masters' Nightmare Season 1, Episode 10 Stalked by Marita A. Hansen

Stung (Zombie Gentlemen) by Merikan, K.A.

Who's Riding Red? by Liliana Hart

Wicked Angel by Celia Jade

The Becoming - a novella by Leverone, Allan

Daring Dane (Intoxicating Passion #3) by Tatum, Felicia

The World of Caffeine by Weinberg, Bennett Alan, Bealer, Bonnie K.