Thinking in Pictures: My Life with Autism (11 page)

Read Thinking in Pictures: My Life with Autism Online

Authors: Temple Grandin

Tags: #Psychopathology, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Autism Spectrum Disorders, #Patients, #General, #United States, #Personal Memoirs, #Grandin, #Biography & Autobiography, #Autism - Patients - United States, #Personal Narratives, #Autistic Disorder, #Temple, #Autism, #Biography

I love nothing more than surveying a plant I've designed where the animals are calm and quiet. One third of the cattle in the United States are moved through handling facilities that I have designed. (Photograph copyright © by Rosalie Winard)

This is an aerial view of my most intricate design, a buffalo-handling facility at the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge. It took 26 drawings to complete this facility, which is operated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

I have designed humane restraint systems for both sheep and cattle. As a result of my autism, I have heightened sensory perceptions that help me work out how an animal will feel moving through the system.

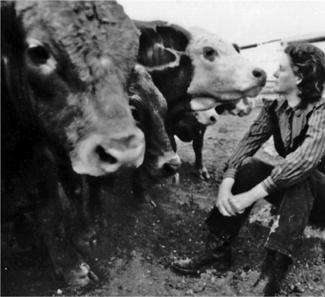

In my work on cattle behavior at Colorado State University, I sometimes like to get a cow's eye view of the situation. (Photograph copyright © by Rosalie Winard)

I met Dr. Oliver Sacks when he first wrote about me in An Anthropologist on Mars. His groundbreaking descriptions of people with various neurological disabilities have improved our understanding of the often enigmatic workings of the human mind. (Photograph copyright © by Rosalie Winard)

In 1994 I testified at a congressional hearing on the humane handling of crippled animals. (Photograph copyright © by Rosalie Winard)

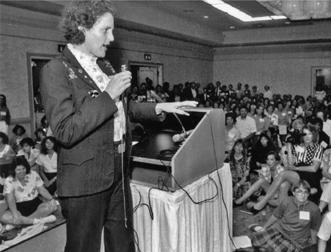

I regularly lecture all over the United States on livestock handling and autism. Here I am addressing the annual meeting of the Autism Society of America. (Photograph copyright © Rosalie Winard)

A third test given by Joan Burleigh, called the binaural fusion test, showed that I have a distinct deficiency in timing sound input between my two ears. In this test a word is electronically split so that the high-frequency sounds go to one ear and the low-frequency sounds go to the other. When the low-frequency part of the word went to my right ear, I was able to hear 50 percent of the words correctly. When the low frequency was sent to my left ear, I became functionally deaf and only got 5 percent of the words correct. “ Woodchuck ” became “ workshop, ” “ doormat ” became “ floor lamp, ” “ padlock ” became “ catnap, ” “ therefore ” became “ air force, ” and “ lifeboat ” became “ lightbulb. ” While taking the test I knew that “ catnap ” and “ floor lamp ” were wrong, but I thought that “ workshop ” and “ lightbulb ” were correct. I often figure out words by the context. If I am at work on an equipment design project, I know that an engineer probably will be talking about a workshop instead of a woodchuck.

Dr. Burleigh has tested other people with autism, and they show the same pattern of hearing deficiencies. She has been able to improve the hearing abilities of some people with auditory processing problems by placing a plug that filters certain frequencies in the most impaired ear. She explained to me that the kinds of problems I have in processing speech indicate defects in my brain stem and possibly the corpus callosum, the bundle of neurons that allows the two halves of the brain to communicate. The brain stem is one of the relay stations that send input from the ears to the thinking parts of the brain.

The techniques used during some of these tests have been available for more than twenty years, but nobody used them on people with autism, mostly owing to a lot of old-fashioned thinking. Working with the electrical engineers helped Dr. Burleigh to look at sensory processing in a new light. Professionals in the field of educating autistic children have largely ignored sensory problems and favored behavioral theory. Edward Ornitz and Peter Tanguay at UCLA documented abnormalities in the brain stem of autistic children more than ten years ago. Dr. Ornitz wrote a major review of the scientific literature on sensory processing problems in autism in the

Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry

in 1985. He stated that people with autism either overreact or underreact to different stimuli, and suggested that some of their deficits could be caused by distorted sensory input. But his important paper was overlooked by educators, who had completely embraced behavior modification methods at the time and ignored the impact of sensory problems.

My auditory problems are very mild compared with those of individuals who are more severely afflicted with autism. Some people have lost all or almost all ability to understand speech. Others have such acute hearing that everyday noises are completely intolerable. One person said that rain sounded like gunfire; others claim they hear blood whooshing through their veins or every sound in an entire school building. Their world is a confusing mass of noise. One woman said she could not tolerate the sound of a baby crying even when she was wearing a combination of earplugs and industrial sound-protector earmuffs. These symptoms are similar to those of people who have had brain stem injuries in an accident, some of whom cannot abide the smallest amount of noise or bright light. Certain types of head injuries create symptoms that partially mimic autistic auditory problems. A girl who was hit on the head during a riot told me that she had auditory problems similar to mine and could no longer ignore distracting background noise. I sometimes have small auditory tune-outs when my ears shut off and I start to daydream. If I work hard to pay attention, I can prevent these lapses, but when I get tired I have a greater tendency to tune out. Now I have control over this, but a person with greater auditory processing difficulties may not be able to gain such control.

Darren White, a young man with autism, wrote that his hearing faded in and out. Sometimes it was loud and sometimes it was soft. He described the sensation in the journal

Medical Hypothesis

: “ Another trick my ears played was to change the volume of sounds around me. Sometimes when other kids spoke to me I would scarcely hear, then sometimes they sounded like bullets. ” Other hearing problems can include a buzzing sound in the ears. I sometimes hear my heartbeat in my ears, or I hear a kind of electronic noise like the sound that accompanies a TV test pattern.

Some autistic children do not pay attention to spoken language. Jane Taylor McDonnell wrote that her two-year-old son could not respond to simple spoken commands. He had to figure out what people wanted by looking at their gestures and the things in the room. Autistic children with echolalia help themselves understand what has been said by repeating it; Donna Williams stated that if she didn't repeat the words, she only understood 5 to 10 percent of what was said. Children with echolalia appear to have severe speech perception problems. In

Somebody Somewhere

, Donna writes, “ As a child I had been echolalic and had difficulty learning the purpose and significance of language. ” She had problems with perceiving both the words and the intonation or tone of speech as a seamless whole. When she was young, she thought that the intonation of a voice was the words. If she listened to the intonation, she could not hear the words.

Therese Joliffe also used echolalia to help her learn language. In the December 1992 issue of

Communication

, published by the National Autistic Society in England, she explained how she usually loses the first few words when someone speaks to her, because it takes her a while to realize that somebody has spoken. It was a long time before she figured out the purpose of speech. When she was young, speech had no more significance than other sounds. To learn that speech had meaning, she had to see words written on paper. After seeing the words, she began to recognize them in speech.

Jim Sinclair also had to learn that spoken words had meaning. He described the difficulties he experienced in

High-Functioning Individuals with Autism

, explaining that “ speech therapy was just a lot of meaningless drills in repeating meaningless sounds for incomprehensible reasons. I had no idea that this could be a way to exchange meaning with other minds. ”

It is likely that some of the people who are nonverbal fail to develop language because not enough speech gets through their dysfunctional auditory system. Both Joan Burleigh's auditory test and recent research by Japanese scientists at the University of Tokushima School of Medicine indicate that abnormal brain stem functioning is the cause of at least some of the problems with understanding speech. Dr. Hashimoto and his colleagues found that nonverbal people with autism have smaller brain stems than normal, and D. G. McClelland and his colleagues at Queen's University in Belfast, Ireland, found that so-called low-functioning individuals who are unable to speak show abnormalities in brain stem function when measured by a test that determines the brain stem's ability to transmit nerve impulses.