Thirty Rooms To Hide In (2 page)

Read Thirty Rooms To Hide In Online

Authors: Luke Sullivan

Tags: #recovery, #alcoholism, #Rochester Minnesota, #50s, #‘60s, #the fifties, #the sixties, #rock&roll, #rock and roll, #Minnesota rock & roll, #Minnesota rock&roll, #garage bands, #45rpms, #AA, #Alcoholics Anonymous, #family history, #doctors, #religion, #addicted doctors, #drinking problem, #Hartford Institute, #family histories, #home movies, #recovery, #Memoir, #Minnesota history, #insanity, #Thirtyroomstohidein.com, #30roomstohidein.com, #Mayo Clinic, #Rochester MN

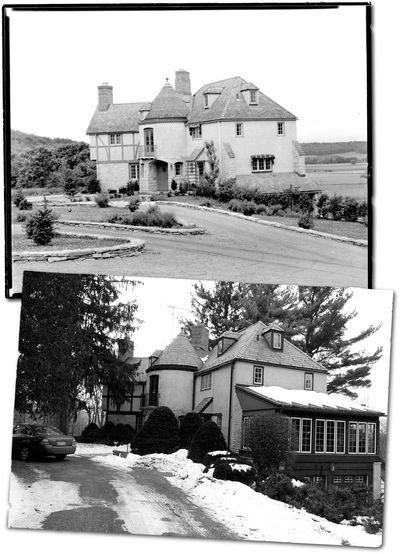

The Millstone in 1928 and 2008.

Rochester, Minnesota, is a rich little town. The Clinic had been producing buckets of cash since the 1920s – and let it be noted here, 1920’s money was

real

money. The large houses that began springing up around the Clinic were baronial estates built in a time when “cutting corners” meant cutting actual corners, like the edges of magnificent scrolled woodwork surrounding a home’s five or six fireplaces. Many of these estates went up on the hills southwest of the Mayo Clinic, an area nicknamed “Pill Hill.” Our home, however, was four miles out in the country.

You couldn’t just pull into the driveway of the home my father purchased in 1954. That would be the cymbal crash without the drum roll. No, first you had to drive up into the hills and after turning off onto successively thinner and thinner roads, you came at last down a lane shadowed by 50-year-old balsam fir trees which stood like bodyguards obstructing your view of the house until the last possible second.

And then …

then

when you turned into the driveway between the giant stone gate posts, you’d had the proper warm-up for your first viewing of the great house we called the Millstone. This would be the part where the opening horns of Tchaikovsky’s

Capriccio Italiane

would begin and the camera would crane up and pull wide to show the four acres of Minnesota summer that were the sovereign kingdom of the owners.

It wasn’t the size of the Millstone and its grounds that made you want the house; it was the sense of stability to the thing. It had been there a quarter-century by the time my father pulled into the driveway and the ivy already clung to its sides; the red slate roof was veteran to a thousand Minnesota snowstorms, and the windows on the third floor looked down on you and said no matter how long you lived, the house would outlast you. Even as an owner, you only visited.

Half-timber English Tudor in style, with a mix of brick, stucco and wooden accents, it featured a circular tower topped with an imperial cone, giving an overall effect of a castle masquerading as a family home.

My father came up with the name Millstone in a sour mood as he signed the first of many checks assuming ownership. In Biblical times, of course, millstones (once they’d served their grinding purposes at the mill) were tied around the necks of condemned prisoners before pushing them into deep water. Had it been my mother who’d named the house, she’d have christened it with a gentler, more poetic name – in fact, she did so, in two letters: “Green Gates” in one, “Meadowlark” in another.

Like many homes of English design, the rooms were small and you warrened your way from one to the next. Kip, seven years old when we moved in, often found himself calling to his mother from “somewhere” to ask “where he was.” It was indeed a large house.

Sudden wealth is an idea America has grown used to, even bored with. But in 1954 it was still called without embarrassment the American Dream and here at the Millstone it came true for my parents, Roger and Myra. Since moving to Rochester in 1950, the young couple had lived in a tiny farmhouse and now found themselves moving into a 30-room mansion.

Back in the farmhouse, they’d had only a few rooms to furnish and so the first year at the Millstone saw rooms that were sparsely furnished or bare. But they had money now and Roger and Myra weren’t ashamed to spend it. In the year 1954, they began living their American dream without a trace of today’s cynicism or self-consciousness. This was a time long before America became aware of its consumerism, its debt, and its profligacy. Myra and her hard-working husband had done their time. They’d scraped by on a medical student’s salary, lived off the vegetables from the farm’s garden, burned Sears catalogs in its furnace against the winter, taken the bus on their big night out and split the entrée when they got there. Now after a year of residency at the best and most famous medical institution in the world, Roger had been asked to join the staff at the Mayo Clinic full time.

They had arrived.

And that October 7th, so did I; a bare month before we moved into the giant house.

“We acquired the home we will probably live in for the rest of our lives,” wrote my mother in a letter to her parents, “and added another little boy to our wonderful family! There will surely never again be

two

such momentous events in such a short period of time in our family!!”

Other than Dad dying and our moving out of the Millstone, she was right.

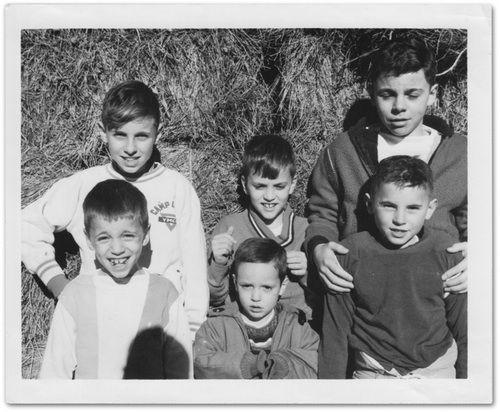

In front of the haystack in the Low Forty in October of 1962.

Front row from left: Luke, Collin, and Dan.

In the Back: Jeff, Chris and Kip.

40 years after we moved out of the Millstone, I’m sitting in my mother’s study going through a box of old family photographs.

Was there some kind of national photo law in the ‘50s

?

(“Okay, on ‘three’ I want everyone to look into the sun, squint hard and make an ugly face, alright?”)

It’s likely that the proud fathers were all saying, “Look at the birdie,” but in the pictures everybody is staring flat into a retina-frying super-nova.

I squint back at the photos. I can see the details. They’re right there in front of me, but no matter how I try to inhabit the moment captured there, it is a fly suspended in amber – I can see but not touch.

I want to stick my head through the black-and-white plane and look off to the left and to the right, to see what was happening before each picture was taken, what happened after. But each paper memory is frozen; every football hangs in the autumn air forever an incomplete pass; every set of birthday candles forever

about

to be blown out. The photos are clear but they don’t show me what happened to my family in July of 1966. They don’t tell me who my father was, or what went on in the hotel room where he died, or why it seemed perfectly normal to be laughing at his funeral.

After that day in the church pews, my brothers and I relived the hot summer of ’66 many times. But in the years of reminiscing, the stories seemed to become shortcuts; they became what we

remembered

we remembered. We started to agree on things, to rehearse the history and over time the story of our father’s death began to feel abbreviated, assembled by committee; like a JFK Warren Report where each citizen could recount only his point of view

– a car backfired, a lady fell to the grass

– and the thing ultimately remained a mystery. On the cop shows, they’d call my father’s death a cold case.

My mother enters the study. She’s carrying some carousels full of my father’s collection of photographic slides. As we talk, I begin to take them out and one by one arrange them in chronological order on the floor; this pile, 1950; that pile, ’51. When I finish organizing, there on the carpeting of my mother’s study we see a graph; a mathematical goodbye letter Dad left for us to read 40 years after his death.

1950 is a tall column of Kodak moments, a foot high.

The stacks for ‘51 through ’54, not as tall.

‘55 through ’58, smaller still.

Until the last column.

One slide.

1962.

A hundred slides in 1950. And one in ’62. It’s as if Dad didn’t move out of our lives all at once but packed a chair off in 1950, a desk in ’53, bit by bit until ’62 when he was gone, leaving this one last slide which stands out in its solitude the way a good-bye letter stands out on the mantelpiece of an empty house.

Tellingly, it isn’t a picture of us but of the house we lived in – taken in the summer of ’62 and, from the look of the shadows’ vertical drop, around noon. The bright sun throws the windows of its many rooms into shade and I wonder what we were doing in there the moment the shutter snapped outside.

The photographic evidence examined, my mother and I discuss where else I might find pieces of my family history. Stories that haven’t been rehearsed. Artifacts of my father’s life that aren’t already on display in the family museum.

All history, including family histories, involves archeology of a kind – we uncover things. The archeologist unearths bones, translates hieroglyphs; as does the family historian in his way, unearthing old photographs instead; reading old letters, old newspapers. We both try to reconstruct our ancient skeletons and if some parts are missing, we make guesses, piece together what we can and step back to look at the thing.

I have only these slides and photographs, which I’ve looked at many times. Maybe I can dig somewhere else; through some other box, through my brothers’ diaries maybe, or the letters my mother’s packed away. Perhaps then the shape of the dinosaur will begin to loom out of the mist.

I pick up the first thread and think, there’s also that old photo album from my father’s childhood. And the family films, there’s those. Plus the notes from Dad’s psychiatrist; nobody’s ever asked to see

that

file, much less the medical examiner’s report. Dad’s doctor friends will probably remember things, too. There’s even that police officer in New Ulm who arrested Dad. Is he still alive? And of course, there’s Mom. She could retell the story. Maybe I’ll just dig it

all

up with a noisy smoking backhoe and sift through everything under a bright bank of klieg lights. Maybe then I’ll be able to reach through the amber, to lean into the photograph, and All Will Be Revealed.

40 years later, my mother is still grieves the final years of her husband’s life. She won’t admit this, but I think she does. She won’t talk about the old days without being asked and then her answers are short. “Why do you want to know such horrible things?” It almost seems to offend her, like I’m some reporter shoving a mike in her face. But she says she’s willing to try.

“This remembering you’re asking me to do isn’t going to be easy,” she admits. “Worse, it may not even be fair. The chance to get even by painting him meaner than he actually was will be tempting. He’ll just have to take the chance that maybe he blew all hope of being remembered fairly.”

There is some anger in her voice today. There is regret, too. And, strangely, some shame.

“I hate that something so

ordinary

happened to my marriage.”

She says ordinary because what happened to her husband and to her family seems like a soap opera now. The shame is harder to understand. Perhaps she thinks she could’ve stopped it from happening; not one of us six boys sees how, but she feels it nevertheless.

From her shelves, I bring down a scrapbook she made for Roger in 1945, right after they married. It’s the story of their courtship written as a keepsake for her new husband and it’s the first time I’ve ever seen it. It’s full of ticket stubs from ancient movies, matchbooks from restaurants long closed, hand drawings by an effervescent 22-year-old girl, and the whole thing smells like it’s spent a lot of time in a trunk.

She cringes at some of the writing. “Embarrassing!” she says turning a page. “That letter was pretentious. Straining for effect.”

“But I was only 22”, she softens. “I was probably trying to sound grown-up and judicious for my folks.”

She turns to her desk and fiddles with the tape recorder I’ve set up. We’re settling in to talk about the old days and about the girl who made the journal I’m holding.

Paging through this journal, the romance of Roger and Myra seems like an old black-and-white movie. They were two “co-eds” from the 1940s; they went on double dates to football games, met at the library between classes, and had real malteds at real malt shops. He, with his dark Irish good looks and brown eyes for the Florida girl to swim in; she, also dark-haired, short like her father, and a thin waist for the minister’s son to put his arm around.

I press RECORD and my mother begins to talk about the co-eds and how they came to live with six sons in a house with 30 rooms called The Millstone.