Thirty Rooms To Hide In (28 page)

Read Thirty Rooms To Hide In Online

Authors: Luke Sullivan

Tags: #recovery, #alcoholism, #Rochester Minnesota, #50s, #‘60s, #the fifties, #the sixties, #rock&roll, #rock and roll, #Minnesota rock & roll, #Minnesota rock&roll, #garage bands, #45rpms, #AA, #Alcoholics Anonymous, #family history, #doctors, #religion, #addicted doctors, #drinking problem, #Hartford Institute, #family histories, #home movies, #recovery, #Memoir, #Minnesota history, #insanity, #Thirtyroomstohidein.com, #30roomstohidein.com, #Mayo Clinic, #Rochester MN

Mom, February 2, 1966

Roger left home this morning for St. Petersburg. Dr. Haslett called from Florida last night to say Roger’s mother was in a coma and not expected to live through the night. I have not yet heard from Rog so I do not know if he found her still living when he arrived this afternoon. Poor man – this is a very difficult time for him, trying to re-establish himself at the Clinic and in his work – this could have come at a worse time (while he was in Hartford) but only just barely.

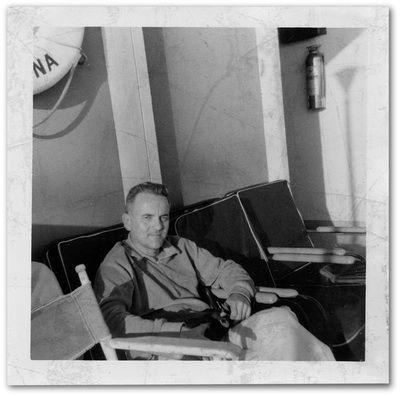

The very last photograph taken of my father.

St. Petersburg, February 1966.

Chris’s diary, February 3, 1966

Things around here are like a soap opera. Dad just gets back from an insane asylum cured from drinking. First day of work, his mother dies. Oldest son far away in California college. Jeff smokes, does bad in school. Luke is a klepto and a smoker.

The weather records for Rochester, Minnesota, say January 29th, 1966, broke a record when it reached 30 degrees below zero. It couldn’t have been much warmer five days later, the day my father started back at the Clinic and got the call about his mother.

On the flight to his mother’s deathbed in St. Petersburg my father wrote a letter to his oldest son Kip on the back of the meal-service placemat. Somehow, during what had to be a stressful week of coming back home and returning to work, my father was able to come out of whatever dark waters held him and – in a voice that was calm, wise, and loving – write the letter reprinted here. Of all the artifacts in the family museum – the ancient photographs, the two frames in the Christmas film, the audio tape – it is a letter, on paper, which shows most clearly the man my father was. My brother Kip still keeps this letter in his desk.

Dad’s letter to Kip, February 2, 1966

Dear Kipper – Pardon dinky stationery. Am 5 miles above Illinois in the bright shiny sky – heading south to St. Petersburg on a sad trip.

My mother is very sick & am doubtful that she will be alive by the time I get there. Got a call last night from her MD that she was in the hospital in oxygen, chest pain, difficulty breathing, high fever, coma & a “gallop rhythm” to her heart beat – all of which adds up to little hope for life.

Part of the sadness will be closing & leaving the house, disposing of her personal things and the few things that may remain of my father’s. Grief – over a near one’s death – is a mixture of sad feelings I think. Partly for ourselves – because we miss the familiar being & the good things that that person’s life has meant to us – but perhaps we grieve more because life is good and beautiful and that person can no longer share it, feel it, love it & live it.

On the other hand – when one is almost 80, as she is, with little strength to do even necessary things – let alone exciting things – when pain is a constant concern – then death may be very welcome. Isn’t it interesting to speculate, too, as to whether death is really an end or a beginning.

Are the views of the dying [just] hallucinations or really vistas of another reality that we the living do not understand? My romantic old man in his last hours said he saw a land of flowers and long mountains & happily said he was going on a long trip – he loved seeing things that he had never seen before. How do we know that we aren’t in heaven now? (Relax, I’m not off my rocker.)

I know there have been so many times in my own life when there was such happiness that “heaven” couldn’t be any better – seeing the happiness on the faces of a child or its parents after a tough life-saving operation, feeling love in your mother’s arms, drifting down the sunlit Mississippi River on a warm day (there really are “a thousand years of music” in those hills), feeling your triumph and happiness on my shoulders after a hockey game – “feeling” the beauty in Tchaikovsky’s violin concertos – etc. etc. Maybe all this is heaven – at any rate, who needs more?

In spite of the sadness of my present mission there will be some happiness. I’m renting a car and I have my swim suit and I’m going back to a place I know – where the sand is white, the sun is hot, the palm trees whisper and the Gulf of Mexico is green and clear. Your mother and I went swimming there 30 years ago. I might even dig up a fishing pole.

Kip, take time to live your days well – remember the happiness and the good in each one of them and make them good. If you do, then all the rest of your days and hours will not only be good but they’ll get better as time goes by – even the troubled ones.

My only regret is that until the last few months I never took time to really think about my feelings. Be good to yourself, and if you are, then you’ll be gentle with others – perhaps they aren’t as wise and strong as you – and they’ll love you for it.

All my love, Dad.

Kip had stored this letter away and uncovered it – a year after Dad’s death – while packing to return home from his sophomore year in college. Re-reading it brought on his first wracking cry over the loss. When Kip brought the letter home, we passed it around the circle and after finishing it each of us looked up at the others, wishing more than anything we’d known the author.

* * *

Roger’s mother was alive when he got there, but barely conscious. After a week she seemed to stabilize and Roger felt he could return to Rochester and did so. But on February 14th he got the phone call. And when he went back for his mother’s funeral he took me along.

Why he chose his fifth son for this trip no one knows, including my mother.

I didn’t know Irene very well; I’d sat in her bony, lifeless lap perhaps twice, quietly traded the “Grandma Rock” jokes with my brothers, yet somehow I was now the chosen grandchild to see her off to her maker. Dad and I spent the week together in St. Petersburg and to remember the occasion, I packed what would be the first of my personal diaries.

I also packed my favorite Christmas gift, the Kodak Instamatic camera.

In the very last series of pictures of my father, we are on the beach together.

First, Dad has the Instamatic and it’s pictures of me feeding popcorn to gulls. Now I have the camera and Dad is on a beach chair, pool in the background. He’s smoking a cigarette and reading a paperback. Even with the magnifying glass I can’t read the book’s title.

But going back to the shot he took of me feeding the gulls, I can see he set the book on the beach chair so he could take my picture. The book is

The Koka Shastra

: an ancient Indian text of erotica and sexual positions.

Looking at a small grainy image of a paperback left on a beach chair 40 years ago, I see that my parents were trying to reconnect, to rejuvenate their love life. When Dad returned from Hartford, Mom had surprised him with a completely new bedroom; new bed, new dressers, new side tables. A sweet gesture: “We can love each other again. Here is our bedroom. Here is where we can be husband and wife again.” I was 10 when she refurbished the master bedroom at the Millstone and at the time thought simply, “Cool furniture, Mom.”

Returning now to the very last picture taken of my father I see he looks pensive, sitting in a chair on a dock in Florida; pensive; not troubled really; just inward; distant. When I look at him I wonder what he is thinking. In his final photograph he’s looking right into the camera, not a pose a man takes when he’s hiding something and perhaps he wasn’t hiding. Maybe he thought he was going to make it. Or perhaps it was an honest look into the lens, a “Hey, everybody, this ain’t gonna work but I’m enjoying this last lap around the track.” Maybe he was thinking I’m rid of the old witch. I study the picture under a magnifying glass searching for some clue. When I get too close it’s just black and white shapes on shiny paper; too far back and it’s just a picture of a man.

Two weeks after that final picture on the beach, Dad updated his Last Will and Testament and made some minor changes, still leaving everything to Myra and his six boys. Perhaps it was his mother’s death that made my father consider his own mortality. Or perhaps he was already dipping his toe in the River Styx. Given what the police would find on the dresser of the hotel room where he died, the latter seems more likely.

Looking out the window to the left of the main front door.

Mom says she knew Dad began drinking again soon after he returned from his mother’s funeral in Florida.

There was now only one bottle of booze in the Millstone: gin, kept on hand for visitors and Clinic gatherings. Mom and Dad had agreed it would be okay to keep one bottle around the house as long as Mom was in charge of it and it was kept in a locked cabinet in the dining room. One March evening Myra had company and when she went to the cabinet she saw the lock had been compromised. It was broken but didn’t

look

broken; a skilled hand had jimmied it. And the level in the gin bottle was lower than it ought to have been.

Then two weeks later Dad’s cover was blown completely. A visitor remarked to Mom that the gin and tonic she’d just prepared for him from the cabinet bottle contained no alcohol whatsoever. Standing there in front of a visitor who could also put two and two together, Mom realized Dad had drunk the entire bottle and refilled it with water. Dad had not just jumped off the wagon. He’d thrown a Greg Louganis reverse two-and-half with a triple twist.

Mom later said that after the switching-gin-for-water trick, she began looking through the house for hidden bottles and finding no stash inside, looked in the back of Dad’s MG. There, like a body in the trunk, was Old Grand Dad. Reappearing at the Millstone along with Old Grand Dad were old behaviors.

Chris’s diary, March 9, 1966

Dan and I went to a movie tonight and Dad picked us up after. On the way home Dad kept telling us that he was hen-pecked. “Mom made me get Pagan. Mom made me put up the gate on the driveway to keep the dog in. Mom loves her books. Mom loves little pets. Mom is a child.” God that’s irritating. I don’t notice much change from his ways in the days of yore. Damn it.

The final storm at the Millstone began with a blizzard.

My father was scheduled to attend a children’s clinic in Fairmont, Minnesota, 120 miles west of Rochester. At these clinics, school nurses would bring in children – sometimes 100 a day – and Mayo Clinic doctors would do triage, referring them to nearby hospitals. When Dad began the drive to Fairmont, it was still just a snowstorm.

Chris’s diary, March 23, 1966

We’ve had the biggest blizzard we’ve had in a long time. Trees are down everywhere. Dad’s out of town at some work thing and his car stalled on the way home and he had to stay at a farm. He won’t be home tonite either.

Dad’s boss, Dr. Mark Coventry, today

He was scheduled to do a children’s clinic in Fairmont, Minnesota, but simply didn’t show up for it.

He told me that he had to stay overnight in a motel on the way to the clinic because of the blizzard that had hit Minnesota. Of course, by then, I didn’t believe him. He simply didn’t show up at the children’s clinic and of course the people there called me, asking, “Where is Dr. Sullivan?”

As it turned out, the morning he was supposed to be there he was arrested for drunken driving by the police.

From the files of the New Ulm, Minnesota, Police Department, March 23, 1966

Nature of report:

D.W.I. Man leaving motel. Seems to have too much drink to drive

.

Report

: I received the call by radio from officer Stoll. I went on Broadway and saw the car, an MG convertible, license 1 GI 275. At 7th N. & Broadway the car stopped in the left lane to make a left turn. At this time I approached the driver and asked him to step out of the car. He was unsteady on his feet. Also the smell of some sort of alcohol drink was on his breath. He said that he was on his way to Fairmont, Minn. to attend some sort of clinic for children but was caught in the snow storm and had to stay “at a farmer’s house” for the night. From that time on he has lost a few days and seemed confused as to what day it was.

How my father ended up in New Ulm is a mystery. It’s 50 miles straight north of Fairmont and way off the direct drive from Rochester.

Police report, continued

Dr. Charles Roger Sullivan was taken to the station and given the usual tests, including the State Highway Alcohol Test. A urine sample was obtained and Dr. Sullivan was charged with driving a motor vehicle under the influence of intoxicating liquor. City Ord. 214 Sec. 4. Dr. Sullivan was placed in cell #3. A black bag and his belongings are in the gun locker. $51.00 in paper money & $2.15 in change. He made a phone call to his wife at Rochester, Minn. Dr. Sullivan bailed out at 7:15 p.m. by check and was OKed by the judge to appear in court on 4/2/66 at 10:00 a.m.

Mom said Roger called her at the Millstone with a story about how he’d been pulled over by the New Ulm Police. He said it was because he “didn’t have a muffler and that he wasn’t allowed to drive. That he couldn’t make it home on the night he’d planned.” Mom, having lived with a liar for so many years (plus the fact that it was a spectacularly shitty lie), guessed correctly, called the New Ulm Police and discovered the truth.

When Roger got home he didn’t bring up the arrest, of course. When Mom told him she knew about it and asked him – probing to the hoped-for response of “Maybe I need to go back to Hartford” – all she got was a clipped “Well, I guess we’ll have to pay more for car insurance now.”

Mom’s letters to her parents, March 23, 1966

We have had a serious set-back but a conversation by phone with the Hartford doctor encourages me to take it as typical and not to be discouraged. That – plus the blizzard – has kept my mind completely occupied. I’ll begin writing again in a few days. Don’t take a silence to be a desperate sign. It’s just that situations like this drain away all my energies and interests and require so much of me to try to deal with everything to everyone’s advantage. All is now well so do not worry.

Mom, today

Looking back, that conversation with the Hartford doctor now seems astonishing. How could he have just accepted news of a DWI and assure me, “Oh now, it’s not the end of the road. No need to be alarmed”? He didn’t stay on the phone with me very long, there was no back-and-forth, no question and answer. Just a curt “Don’t worry” and he hung up.

I remember looking at the snow falling outside, wondering “What am I going to do now?”

Soon, Dad no longer tried to conceal his drinking by hiding in a motel room a city away. We were back where we started.

Chris’s diary, April 9, 1966

The whole family left for Easter vacation in LaCrosse, Wisconsin, around 10:30 this morning. [The handwriting changes here, appearing angry.]

God Damn it! Last night dad started drinking again. He was juiced the whole night. Mom and us left the motel with him still sleeping it off. We rented a car and came home. Things will be just like old times. SHIT, I KNOW RIGHT NOW NEVER TO EVER DRINK IN MY WHOLE LIFE.

Mom, today:

That was a bad night, that one in LaCrosse. I remember pouring a bottle into the motel sink. It didn’t raise his ire; he was too drunk by then to care. I left him in our room and came next door and slept on the floor of the room where you four little ones were. I remember the next morning one of you asked “What are you doing down there, Mama?” and I lied. I said I was “exercising.”

Mom rented a car and drove us home and a pall hung over the Millstone on Easter Sunday. After this incident the letters from Rochester stopped. In Grandpa’s bound collection of letters, Myra writes only one letter in all of April and June, and not again until a week after her husband’s body arrived back in Rochester.

Dr. Mark Coventry, today

Well, by then it was out of my hands. He was coming into work impaired from drinking the night before. The Clinic’s Board of Governors decided that with several warnings already, with his institutionalization, and now with him drinking heavily again soon after Hartford, they weren’t going to put up with it any longer. They suggested he leave.

They said they “would do everything they could” to help him find another place but that’s always difficult with a history like his. Still, I helped him arrange a trip to the Southeast; he seemed particularly interested in settling there. And so we wrote letters to people in Florida, in Georgia. But of course those letters have to be honest.

And so the young medical student who’d aspired to be Albert Schweitzer was kicked out of the most prestigious medical center in the world. And it was clear they weren’t going to give him a good recommendation

.

On May 24th, my father began his final, frantic, and futile trip around the country looking for a new job.