This Great Struggle (16 page)

Read This Great Struggle Online

Authors: Steven Woodworth

The attack fell on McClernand’s division and gradually by weight of numbers overwhelmed its regiments one by one from east to west, curling it back on Brigadier General Lew Wallace’s center division. Wallace had previously sent only slight aid to McClernand because of Grant’s orders to remain in place and do nothing, but his division was able to halt the Confederate offensive around midday.

From the point of view of the Confederate plan, the stand of Wallace’s division was irrelevant. A yawning gap on the right of the Union line now left the way wide open for the entire Fort Donelson garrison to march out and take the road for Nashville and a reunion with Johnston’s main body. Buckner, the only professional soldier among the top three in the fort, found Floyd on the battlefield and suggested the time had come to leave. Floyd agreed, but before he could issue the order for the withdrawal, Pillow found him. Flushed with victory, Pillow persuaded Floyd to cancel or postpone the withdrawal and order the troops back into the entrenched lines of the fort to rest and eat a meal. Pillow apparently thought the Yankees so badly whipped that the victorious Confederates could retire at their leisure.

A staff officer caught up with Grant as he was coming ashore after his conference on Foote’s flagship and informed him that the army was fighting a desperate battle. Grant galloped back and arrived just as a lull was settling over the battlefield after Wallace’s noon repulse of the Confederates. Sizing up the situation Grant decided the Rebels had attempted to break out and had failed to do so. “The one who attacks first now will be victorious,” Grant told a staff officer. “The enemy will have to be in a hurry if he gets ahead of me.” Grant gave immediate orders for an attack all along the line. On the center and right, Wallace’s troops and some rallied units of McClernand’s wrecked division drove back toward the positions McClernand had lost that morning, taking key ground.

On the Union right, Grant’s old West Point professor, Brigadier General Charles F. Smith, led his division from the front, huge white mustache streaming over both shoulders. Smith forbade his men to stop and fire until they got inside the Confederate breastworks. The position was extremely strong, but the Confederate lines were thin because most of the troops there had been pulled away to take part in the breakout attack. Behind Smith’s charismatic leadership the Union line surged up to the works. The color-bearer of the Second Iowa leapt over, and then hundreds of Federals followed, swarming over the breastworks and driving the Rebels back. Darkness and Confederate reinforcements brought their drive to a halt. The Confederates were men of Buckner’s command hurrying back to their defensive positions after Floyd had ordered them to return to the fort.

That night the three Confederate brigadiers held a conference inside the fort. Buckner announced that the Yankees had possession of his lines and from their favorable position could overrun the entire fort at dawn. No option remained, he said, but surrender. Floyd said he dared not surrender; with the accusations leveled at his actions as secretary of war, the Yankees might hang him. Pillow said he would never surrender. A volunteer cavalry colonel named Nathan Bedford Forrest came in and said a way out was still open, apparently unknown to the Yankees. It followed a road immediately along the bank of the Cumberland, and it would involve wading several hundred yards, “saddle-skirt deep,” through an icy backwater. Buckner said if they did that, three-quarters of the men would die of pneumonia, and that would be immoral. It was their duty, he said, to surrender.

Floyd asked if he might turn the command over to Buckner and be permitted to escape personally. Buckner said he could if he got out before the white flag went up. “I turn the command over, sir!” said Floyd. “I pass it,” said Pillow, his next in rank, and Buckner went to look for a bugler and a white flag. A disgusted Forrest led his own cavalry regiment out, along with quite a number of infantrymen who decided to tag along, clinging to the horses’ stirrups when the water got deep. Floyd and Pillow found boats at the fort’s landing—Floyd a steamboat on which he could take some of his men, Pillow an abandoned scow in which he could take a few staff officers as oarsmen. When Grant received Buckner’s note asking for terms of surrender, he responded, on Smith’s advice, “No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works.” Buckner, though grumbling about Grant’s lack of chivalry, had no choice but to accept.

News of the victory thrilled the nation. With 12,392 Confederates heading north into Union captivity it surpassed Saratoga and Yorktown as the largest surrender ever on American soil. The intensity of the fighting was demonstrated by the fact that the 2,500 Union killed and wounded and the 1,500 Confederate were comparable to the numbers of killed and wounded at Bull Run (considerably more for the Union), though only about half as many troops had been engaged.

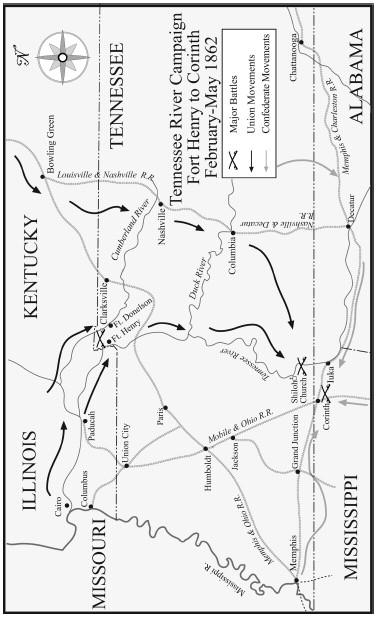

The capture of forts Henry and Donelson was enormously important and might almost be called the first turning point of the war. Up until that time, the Confederacy had had things pretty much its own way, but it never fully recovered from the loss of the forts. The twin February victories gave the Union control of the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers deep into what had been Rebel-controlled territory. Union gunboats, transports, and armies could range up the Cumberland all the way to Nashville and up the Tennessee all the way into northern Mississippi and Alabama. The Rebels could no longer hold positions along the Mississippi in the states of Tennessee or Kentucky because Union control of the Tennessee guaranteed the defenders would easily be turned and possibly trapped. Half the state of Tennessee passed to Union control, and the partial Confederate grasp on the state of Kentucky was gone. Within weeks, Union troops would be poised on the edge of the Deep South states.

Grant became a national hero, and his demand for “unconditional surrender” gave a new meaning to his first two initials. Lincoln soon promoted him to major general of volunteers. The president did not fully realize it yet, but he had found a general who would fight and fight skillfully.

A WINTER OF CONFEDERATE DEFEATS

Washington’s Birthday came six days after the surrender of Fort Donelson and found the armies of the Union quietly encamped, though Grant’s was resting from its earthshaking victories of that month.

In Richmond, the Confederacy had chosen this day, with its associations with the first president and father of his country, to inaugurate its first regular president, duly elected the preceding November in the glow of the Confederate victories of 1861. This of course was Jefferson Davis, the provisional president and only candidate for the regular presidency. The inaugural ceremony was anything but auspicious. A cold rain dripped sullenly out of a low, gray overcast. When the president’s wife, Varina Howell Davis, asked one of the four black footmen who walked slowly beside the barely rolling presidential coach why they wore formal black suits and walked so slowly, he replied, “This, ma’am, is the way we always does in Richmond at funerals and such-like.”

1

It certainly appeared that the Confederacy’s funeral, if the southern slaveholders’ republic should receive any such honor, would not be far off, for the disasters of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, though by far the worst, had not been the only Confederate debacles in recent weeks. On January 19, a division of nearly six thousand Confederate troops under Major General George B. Crittenden (West Point, 1832), son of Union-loyal Kentucky Congressman John J. Crittenden, had attacked a smaller Union division of about 4,400 men under the command of Union-loyal Virginian George H. Thomas (West Point, 1840) at Logan’s Crossroads in Kentucky.

It had been a sharp little fight on a foggy, rainy morning, with the Second Minnesota fighting it out with the Fifteen Mississippi with bayonets over a rail fence and the colonel of the German-speaking Ninth Ohio leading his men in a wild bayonet charge, shouting, “Close your eyes, boys, if it gets too hot for you.” Felix Zollicoffer, a popular but very nearsighted Nashville newspaper-editor-turned-Confederate-general, accidentally rode into Union lines and was shot. The Federals prevailed, and Crittenden’s force retreated in disorder. The defeat would have been significant in destroying Albert Sidney Johnston’s right flank had Buell been enterprising enough to exploit it and the season of the year propitious enough to favor such exploitation. As it was, the fall of the Tennessee and Cumber river forts, coming less than a month later, had ripped open the center of Johnston’s defenses and presented the Union with a far better opportunity than that gained by the victory at Logan’s Crossroads.

Then on February 8 Union sea power and its long amphibious arm struck again, this time on the North Carolina coast. A fleet of specially acquired shallow-draft gunboats under Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsboro entered the North Carolina Sounds, the narrow, shallow waters inside the band of barrier islands off the coast of the northeastern part of the state. The fleet chased away a few Confederate gunboats and suppressed the fire of shore batteries. Then transports landed a special ten-thousand-man army amphibious division under the command of Ambrose Burnside (West Point, 1847), and within less than twenty-four hours the 2,500-man Confederate garrison surrendered, leaving the island in Union hands. Aside from the loss of troops, the capture of Roanoke Island hurt the Confederacy by opening the way for complete Union control of the North Carolina Sounds and their shores, cutting off coastwise commercial traffic and closing a backdoor for materials coming through the blockade to reach the port of Norfolk, Virginia, via the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal and the Dismal Swamp Canal.

Well might President Davis observe in his inaugural address that February 22, “We have recently met with serious disasters,” but, though he admitted that “the tide for the moment is against us,” he maintained nonetheless that “the final result in our favor is never doubtful.” Perhaps, he suggested, God was teaching them to value their liberty by the high cost they paid to win it.

Whatever the cause and purpose of the Confederate disasters that winter, they were not over, and spring at first brought no change of the tide of war. On March 7 a Confederate army of sixteen thousand men under the command of Major General Earl Van Dorn (West Point, 1842) attacked a Union army of about ten thousand men under Major General Samuel R. Curtis (West Point, 1831) in northwestern Arkansas. Despite the death of Lyon at Wilson’s Creek the preceding August, Union forces had steadily pressed Sterling Price’s Confederate Missourians out of that state. Curtis, with his Army of the Southwest, pursued Price into Arkansas.

Retreating into Arkansas, Price’s force again united with that of Ben McCulloch, reopening the previous year’s questions about who should command whom. From far off Richmond, Jefferson Davis decided to fix the problem by assigning his fellow Mississippian Van Dorn to command both Price and McCulloch. Van Dorn had big plans. He would crush Federal strength in Arkansas and then march into Missouri. “I must have St. Louis,” he wrote to his wife, “then huzzah!”

The first step was defeating Curtis, who had learned of Van Dorn’s approach with a more powerful army and had taken up a strong defensive position along the valley of Sugar Creek. Van Dorn planned to march around Curtis, get behind him, and split his own army into two columns, one passing east and the other west of a landform called Pea Ridge and converging in an irresistible pincer movement on the Federal rear. In practice, however, everything seemed to go wrong. Curtis discovered Van Dorn’s movement and turned his force in time to face him, stopping the two Confederate columns on either side of Pea Ridge and hindering their conjunction. McCulloch crept forward to reconnoiter the Union position in front of his column, and a Federal soldier shot him dead. Then Van Dorn discovered that the problem with being in the enemy’s rear was that then the enemy was in his own rear. As a result his army ran low on ammunition with no good way of replenishing. The battle carried over to the next day, March 8, and ended with Curtis’s Federals routing Van Dorn’s Rebels. After the Union victory at Pea Ridge, Confederate forces would never again seriously threaten to gain control of Missouri but would henceforth struggle to maintain some hold on Arkansas.

The Confederacy suffered another, albeit less significant, setback later that month and even farther west. With authorization from Richmond, Confederate Brigadier General Henry Hopkins Sibley (West Point, 1838) had raised a brigade of Texas cavalry the preceding fall and marched it west in hopes of adding the western territories with their gold mines and possibly even Pacific coast harbors to the Confederacy. They got as far as Glorieta Pass, in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains of New Mexico, where on March 28, 1862, a smaller mixed force of U.S. Army regulars and Colorado and New Mexico territorial volunteers defeated them and turned back their expedition.

JOHNSTON PREPARES A RIPOSTE

Battles like Pea Ridge and Glorieta Pass, fought well west of the Mississippi River, were of tangential significance to the Civil War. If the Confederacy won the war and gained its independence, such battles would help decide what western lands the new slaveholders’ republic might own, but nothing that happened out there was at all likely to decide the central momentous question of the war. That question might, by an off chance, be decided east of the Appalachians, but it was most likely to find its answer in the prewar heartland of America, the broad swath of country between the Appalachians and the Mississippi.