This Great Struggle (34 page)

Read This Great Struggle Online

Authors: Steven Woodworth

By this time Grant had come to the conclusion that the only practical way to get the gunboats and transports past Vicksburg was to run them down the Mississippi itself, directly under the guns of the Vicksburg batteries. When he approached Porter with his plan, the admiral agreed to try it but warned that the move would not be reversible. Once the gunboats had run downstream past Vicksburg they would not be able to return until Grant took the Confederate fortress city since the slow upstream run would be suicidal if the Rebels were still manning their guns on the Vicksburg bluffs. Grant agreed, and both officers began preparing their forces. The Army of the Tennessee began a slow and tortuous advance through the tangled swamps and back-channels of the delta country west of the Mississippi, building dozens of bridges and scores of miles of corduroy road (a road surfaced by saplings laid side by side to prevent wheeled vehicles from sinking into the mud).

Meanwhile, Porter prepared a squadron of his best ironclads to run the Vicksburg batteries on the night of April 16, 1863. With coal barges lashed to their sides to provide extra fuel in the remote lower reaches of the Mississippi, the gunboats moved out silently through the dark night, hoping to avoid detection by the Confederates on the bluffs. The Rebels proved too alert, and the heavy guns roared to life as the Union vessels moved into the difficult sharp bend of the river directly in front of the town. The sailors fired back as best they could with their own cannon while helmsmen struggled to keep the vessels on course through the treacherous eddies produced by the bend. For several minutes the roar of the guns was audible many miles away, but when the guns fell silent and the smoke cleared, Porter’s fleet had successfully passed the batteries with only minor damage.

Six nights later army volunteers ran a group of leased transports past the batteries after civilian crews had balked at taking these frail, unarmed, and unarmored craft under the muzzles of the Confederate guns. The civilian boatmen’s misgivings proved somewhat justified, as the Confederate gunners, without the hindrance of return fire, sank two of the transports and badly shot up the rest. Nevertheless, Grant’s resourceful midwestern soldiers-turned-boatmen picked up their shipwrecked comrades, patched up the surviving vessels, and somehow got past the batteries with most of the flotilla intact and usable, ready to ferry Grant’s army across the river south of Vicksburg.

While the gunboats and transports ran the Vicksburg batteries and Grant’s army worked its way down through the swamps on the west bank of the Mississippi and prepared to cross the river, Pemberton remained confused. A simultaneous Union cavalry raid, which Grant had ordered for just that purpose, ranged virtually the whole length of the state of Mississippi, from the lines of Grant’s rear-area forces near Memphis all the way past Jackson and down to where a small Union army under Nathaniel P. Banks was approaching the secondary Confederate bastion on the Mississippi River at Port Hudson, Louisiana. The expedition’s commander, Brigadier General Benjamin Grierson, proved wily and resourceful in creating maximum disruption of Confederate rear areas while dodging all the troops that Pemberton dispatched to catch him. With his enemy thus distracted as planned, Grant prepared to launch his main campaign into the state of Mississippi.

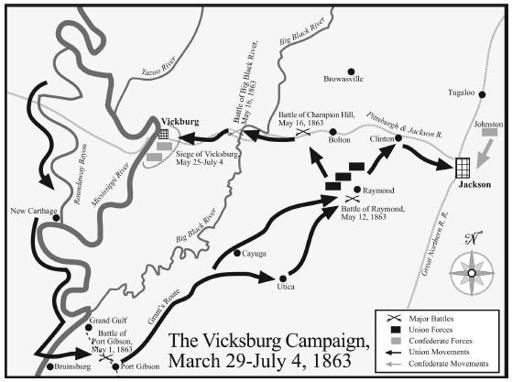

On April 29, 1863, Grant’s army landed on the east bank of the Mississippi River about forty miles below Vicksburg near the settlement of Bruinsburg and moved rapidly inland. The next morning his army defeated a detachment of Pemberton’s Confederate army at Port Gibson. Rather than advancing straight north toward Vicksburg through a terrain of steep ridges and deep ravines, Grant moved northeast. On May 12 one of Grant’s corps defeated another Confederate detachment near the town of Raymond. Two days later, Grant’s troops marched into Mississippi’s capital, Jackson, before turning westward to approach Vicksburg directly from the rear. On May 16 he met and defeated Pemberton’s main field army at Champion Hill, about twenty miles east of Vicksburg. When Pemberton made a stand the next day at the main crossing of the Big Black River, Grant routed him again.

Mentally, Grant kept at least one step ahead of Pemberton, whose befuddled efforts at stopping Grant led to Confederate defeats in five consecutive battles as the campaign progressed through the interior of Mississippi. In a revealing measurement of the abilities of the rival commanding generals, Grant outnumbered Pemberton on every battlefield even though Pemberton had more troops in Mississippi than Grant did.

By May 18, Pemberton’s army had taken refuge inside the fortifications of Vicksburg itself. Grant had made contact with the Mississippi River just above Vicksburg, reestablishing a short, secure supply line. His lines extended along the north and east sides of Vicksburg far enough to the south to cut off the Rebels there from receiving supplies and prevent them from escaping. In less than three weeks since landing in Mississippi, Grant had outmaneuvered Pemberton, won five battles, gained the advantageous position behind Vicksburg that had seemed impossible to reach, and bottled up the Confederate army in what was each day looking more and more like a trap. The campaign had been risky, and Grant had overcome both enemy resistance and incredibly difficult terrain. The result was an operational masterpiece that rivaled and perhaps exceeded Stonewall Jackson’s spring 1862 Shenandoah Valley Campaign as the most brilliant of the war.

Even from the rear Vicksburg proved to be a very strong position, and Pemberton’s demoralized soldiers found that within its heavily fortified lines they had a chance to stop the blue-clad soldiers who had chased them through Mississippi. Grant’s all-out assaults on the city on May 19 and 22 both ended in bloody failure. Regretfully but with grim determination, Grant and his army settled down to a methodical siege, bombarding Vicksburg and digging their trenches ever closer so as to set up a final assault that would be guaranteed success. Meanwhile, Confederate soldiers and civilians inside Vicksburg went on short rations as supplies grew increasingly scarce.

THE CHANCELLORSVILLE CAMPAIGN

During the winter of 1863, while Grant had tried one plan after another to get at Vicksburg from a direction that offered hope of success, Lincoln had decided that the situation in Virginia required a new general there. Burnside’s popularity in the Army of the Potomac had been dismally low since the debacle at Fredericksburg and had sunk lower after the abortive January offensive that his men were bitterly calling “the Mud March,” after the onset of a rainy spell turned the Virginia roads into deep quagmires in which the army’s guns and wagons bogged down. The discontent extended to the army’s generals as well, most of whom were McClellan favorites still bitterly seething about the removal of “Little Mac,” as the adoring troops called him. Some of the generals complained to Lincoln to the point that the president became convinced that the Army of the Potomac could no longer function with its present commander. Sadly, because he admired Burnside’s modesty and dedication, Lincoln replaced him with Major General Joseph Hooker.

An 1837 West Point graduate, Hooker had served with distinction in the Mexican War and then had commanded a division and later a corps within the Army of the Potomac, generally performing well. Aside from that previous service, Hooker’s reputation had been shaped by both his well-known penchant for whiskey and prostitutes and his habit of harshly criticizing each of his army commanders. In a letter that Lincoln wrote to Hooker on assigning him to command the Army of the Potomac, the president gently but firmly admonished the new commander that his undermining of his predecessors, particularly Burnside, had not been commendable and might well have created a spirit within the high command of the army that would make Hooker’s own job more difficult. He also referred to a troubling statement Hooker had recently made to a reporter. “I have heard,” Lincoln wrote,

in such way as to believe it, of your recently saying that both the Army and the Government needed a Dictator. Of course it was not for this, but in spite of it, that I have given you the command. Only those generals who gain success can set up dictators. What I now ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship.

1

Despite the concerns that had prompted Lincoln to write such a letter, Hooker’s tenure in command of the Army of the Potomac began with much promise. He proved to be an able administrator, raising the army’s morale as well as the state of its training and discipline. He also adopted an excellent plan for dealing with Lee as soon as spring weather dried Virginia’s dirt roads. The plan was not unlike the scheme that Grant was simultaneously devising—and would simultaneously carry out—in the Vicksburg Campaign. Brigadier General George Stoneman (West Point, 1846) would lead the Army of the Potomac’s cavalry on a raid deep into enemy territory to confuse Lee. Then while part of Hooker’s army continued to threaten Lee at Fredericksburg directly across the Rappahannock River, the bulk of the army would march upstream, cross the river, and march rapidly to get behind Lee and fall on him from the rear. That the campaign that followed took a much different course than Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign was due mainly to the fact that Stoneman was not Grierson, Lee was not Pemberton, and, most of all, Hooker was not Grant.

On April 27, three days before Grant landed his forces on the east bank of the Mississippi, Hooker put his own army in motion and his troops began crossing the Rappahannock a number of miles above Lee’s headquarters at Fredericksburg. The main body of the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rappahannock unopposed, marched south, and crossed the Rapidan, a tributary of the Rappahannock. Still they met no opposition, and Hooker could only assume that he had stolen a march on Lee exactly as he had planned.

Indeed he had, but that turned out to be almost the last thing that went right for Hooker. Stoneman’s raid proved ineffective and accomplished nothing beyond depriving Hooker of most of his cavalry and thus of his means of discerning Lee’s movements. By contrast, Jeb Stuart, leading Lee’s excellent cavalry, alerted the Confederate commander to Hooker’s approach. Under cover of a dense fog, Lee withdrew most of his army from its positions around Fredericksburg, unnoticed by the large Federal corps of Major General John Sedgwick (West Point, 1837), which Hooker had left on the other side of the Rappahannock to threaten and hopefully to pin down Lee’s main body. Leaving only a single reinforced division to watch Sedgwick at Fredericksburg, Lee marched with the rest of his army to counter Hooker’s turning maneuver.

The main bodies of the two armies made contact on May 1, just as the Federals were about to emerge from a region of dense thickets and scrub forest known locally as the Wilderness of Spotsylvania, which stretched for a number of miles along the south bank of the Rapidan. Fighting erupted, and Hooker’s troops were doing well when inexplicably he ordered a withdrawal into the heart of the Wilderness, where he ordered his army to take up a defensive position. Within the tangled underbrush of the Wilderness, the Army of the Potomac’s two-to-one superiority in numbers was less significant, and its even more dramatic advantage in artillery meant nothing at all. Hooker’s subordinate generals were stunned and confused, able to think of no reason why their army would choose to fight in a place like that, and, indeed, no reason existed except that Hooker had lost his nerve.