This Is Not Your City (4 page)

Read This Is Not Your City Online

Authors: Caitlin Horrocks

Tags: #Fiction, #Short Stories (Single Author)

“Wouldn't be much of any way for me to bring things by, either,” Elsa said.

“Do you know anyone who could give you a ride?”

“I'd do it,” I said. “I could take you.”

They both looked at me. “Do I know you?” Elsa asked.

“No.”

“Then I would pay you,” she said, after a few moments thinking about it. “It would be a help.”

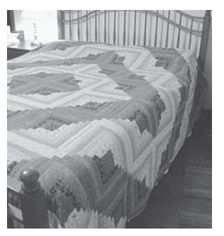

“I'd be happy to,” I said, and I was, maybe because she wore black sneakers with her navy blue dress, or because she spoke to me, or because it was a thing I could do that would get me out of the house, and after eighteen years growing up around people who wouldn't speak to me, I thought it would be nice to have one in my car for a while to talk to. We picked a day and a time, and she gave me directions to her farm, and when I got there it looked just like she'd said. It looked like this:

Every three weeks I drive to her farm to pick her up. I drive to the house, and she comes down the porch steps. She's always waiting on the porch. She's never had me inside and it keeps me uncertain if we're friends, or just friendly with each other. I turn the car around, then it's fifteen miles to the Interstate, forty minutes on 71 to this fancy Amish furniture shop in Olentangy, another half hour to the gallery in the city. People stare at her in Columbus, at her long dress and her hair pulled back hard under her bonnet, and I forget that I shouldn't be startled by it.

Elsa always has at least one new piece for each place, crib quilts and wall-hangings, small pieces to fill demand. Full-size bed quilts take too long. Still, she must spend hours every day away from the kitchen, or her children, or the garden, or whatever else she's responsible for, to produce that much work. I wonder what her husband thinks, what the other women think. In the car she talks about how in the autumn her hands are quick with a certain light, how they shake with the work inside them, and the only

way she's found to calm them is to choose colors, cut pieces, load stitches on the needle. When she talks that way, it's the only time I feel sorry for her, but then I'm sorrier because it makes me happy to know that that's something I have that she doesn't, that if I ever wanted or found the time I could draw or dance or listen to music or just drive too fast with my window open and Elsa can't do any of those things. I didn't think she could have any music, either, until she told me she met her husband singing.

way she's found to calm them is to choose colors, cut pieces, load stitches on the needle. When she talks that way, it's the only time I feel sorry for her, but then I'm sorrier because it makes me happy to know that that's something I have that she doesn't, that if I ever wanted or found the time I could draw or dance or listen to music or just drive too fast with my window open and Elsa can't do any of those things. I didn't think she could have any music, either, until she told me she met her husband singing.

“It's just instruments we can't play,” she said. “The teenagers have sings on Sunday evenings.”

“Sing something for me,” I told her.

“They're all hymns.”

“Sing one anyway.”

“I can't.”

“Why not?”

“I'm married now. I can't sing anymore.”

“That's sad,” I said.

“Why? The sings are for courting.”

“It's sad you had to stop.”

“Why should I care what makes you sad?” she said.

The more I think about it, the more I think that Elsa won't let us be friends after all, and that's one more thing that makes me sad so then I stop thinking about it.

Â

IV. I have a job. I make quilts too, like Elsa, but they're not as good:

If I sold this one as my work, handquilted at four to five irregular stitches per inch, some of the angles on the quilt top crooked and a few of the seams lumpy, it might bring $250

at Buried Treasures, in Martinsberg, $300 if it sold at Annie's Antiques, in Jelloway. $325 at the Treasure Mart in Danville. I'm not nearly as good as Elsa, and I'm definitely not Amish, which doesn't help in the quilt business. $250 minus $60 for fabrics, batting, and thread, divided by 150 hours of work, equals $1.27 per hour. This is why I don't sell my quilts as made by me.

at Buried Treasures, in Martinsberg, $300 if it sold at Annie's Antiques, in Jelloway. $325 at the Treasure Mart in Danville. I'm not nearly as good as Elsa, and I'm definitely not Amish, which doesn't help in the quilt business. $250 minus $60 for fabrics, batting, and thread, divided by 150 hours of work, equals $1.27 per hour. This is why I don't sell my quilts as made by me.

To get technical for a minute, this quilt, with the crooked angles and the lazy handstitching, was machine-pieced out of salvaged, distressed, printed cottons, on an 1886 Singer treadle, filled with flat, all-cotton batting, and quilted with a size 7/9 needle using unwaxed thread. The pattern (Log Cabin: Barn Raising) was popular in northern Ohio from 1865 to 1895, and if I told you that's when this quilt was made, you'd have to know a fair bit about quilts to be able to prove me wrong. Antique quilts go for a lotâ$500 minimum anywhere in Knox County, more in Columbus, but I'm scared to try and show in Columbus because the appraisers there know what they're doing.

I'm not sorry or anything. $500 minus $60 divided by 150 is still $2.93 an hour. I could do better driving to the Wal-Mart in Vernon, but I can't work outside the house because of my mom. She taught me to quilt years ago. I've always done it by myself. Quilting circles seem like a dumb idea. I don't want to sit around and listen to people bellyache. My problems are mine. No one else's. I've never really liked quilting all that much.

Â

V. Please show Mr. Martin that I do math everyday now, more than I did when I was in his class. On my last sale, a double-size Dresden Fan, my hourly worked out to $3.438, but I remembered that when the last number is five or more, you're supposed to round up, and that makes it $3.44. I used a calculator, but please tell Mr. Martin anyway, and that I'm sorry I never understood logarithms. Also, maybe, that quilting takes a lot of geometry, and that I still remember that the Pythagorean Theorem goes like this:

VI. This is my older sister, Melie:

She's twenty-two, four years older than me. She's the pretty one, not that I think I'm ugly or anything, just that it's true, she's prettier. After she finished high school, she left Mom and me in the house to move in with her boyfriend in Vernon. She's still living there with a guy, but I lose track of who she's seeing. She still comes around sometimes and after she leaves Mom says, “If I'm not a grandmother yet, it's not for lack of Melie trying.” I don't tell her that Melie could have made her a grandmother three times over, that I know of. Twice she asked me to take her to the clinic, all the way into Columbus, because she said people might recognize her in Vernon. I said if they did, they wouldn't find out anything they didn't already know about her. So the next time she had a friend take her, and I found out anyway, which goes to show that I was right all along. I don't know why the men don't take her. I don't know why she isn't more careful in the first place. I asked her once and she said what did I know, I'd never been with anybody and I acted like I never wanted to. “My heart's bigger than yours,” she said. “You've got a skinny little heart inside.”

Â

VII. I don't have a picture of my mom. She wouldn't let me take one, but you can picture her kind of like Melie and me mixed up together except older, of course. She's got brown eyes and blond hair that used to be really long until she had me cut it a couple of months ago. I could tell she was sorry to cut it, but she was sorrier to need me to brush it for her, and tie it back, and this way probably works out better for the both of us.

Her hands got bad first, just hurting her and then hurting her so bad they got twisted up. Then her feet and her ankles did the same thing. The anti-inflammatories don't work the way they're supposed to for her. The doctors don't know why. She can't use her hands at all anymore, so I turn the TV on in the morning for her and turn it off at night. She can kind of use the remote control, but not so well, and she gets mad when she can't watch what she wants to. Her hands look like this:

but those aren't her real hands. Here's the citation: <

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File

:Rheumatoid_Arthritis.JPG>.

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File

:Rheumatoid_Arthritis.JPG>.

VIII. Please tell Mr. Kincaid from Civics and US History that I remember that William Henry Harrison, who looked like this:

<

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File

:Harrisonwh-o.jpg>, served the shortest term of any president because he gave a long boring speech in the rain, caught pneumonia and died, and that the moral of the story is that we should keep it short. I remember that Gettysburg was the bloodiest battle of the Civil War but Antietam was the bloodiest day. I remember about how Manifest Destiny was both good and bad because the West was settled but lots of Indians died. I remember that Waterton was founded in 1841. I remember that in 1905, when the trains still ran, a boy died on the

trestle bridge near Gambier because his own father tied him down. I remember that our river is the longest in Knox County, that it is called the Kokosing and that this is an Indian word that means Owl Creek. Tell Mr. Kincaid that even when I'm on 71, heading home from the gallery in Columbus, and all I want to do is stay on the Interstate until it dumps me into Lake Erie, I think of it as our river.

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File

:Harrisonwh-o.jpg>, served the shortest term of any president because he gave a long boring speech in the rain, caught pneumonia and died, and that the moral of the story is that we should keep it short. I remember that Gettysburg was the bloodiest battle of the Civil War but Antietam was the bloodiest day. I remember about how Manifest Destiny was both good and bad because the West was settled but lots of Indians died. I remember that Waterton was founded in 1841. I remember that in 1905, when the trains still ran, a boy died on the

trestle bridge near Gambier because his own father tied him down. I remember that our river is the longest in Knox County, that it is called the Kokosing and that this is an Indian word that means Owl Creek. Tell Mr. Kincaid that even when I'm on 71, heading home from the gallery in Columbus, and all I want to do is stay on the Interstate until it dumps me into Lake Erie, I think of it as our river.

Other books

Breaking Through by Francisco Jiménez

The Problem With Jordan by Joannie Kay

Marja McGraw - Bogey Man 04 - Awkward Moments by Marja McGraw

Murder in the Second Row by Bev Robitai

Keely's Kinky Secrets: My First Foursome (Erotica) by Keely Eve

Miss Julia Delivers the Goods by Ann B. Ross

Murder on the Riviera by Anisa Claire West

Get More by Nia Stephens