This Is Your Brain on Sex (24 page)

Read This Is Your Brain on Sex Online

Authors: Kayt Sukel

Tags: #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology & Cognition, #Human Sexuality, #Neuropsychology, #Science, #General, #Philosophy & Social Aspects, #Life Sciences

“Addiction goes far beyond

just drugs,” said Wolfram Schultz, a neuroscientist at the University of Cambridge who studies risk and reward processing and how they may be involved in addiction. “In the last twenty years, we’ve seen other things can become addictive, like sex, food, or even publicity. Some people are addicted to being in the center stage. When you cross that line and

need

that thing you are addicted to, when you get withdrawal symptoms when you can’t get it, it’s very unhealthy and can be life-endangering.”

Individuals like Kristie, who have dealt with a nonsubstance addiction, know it can cause as much physical and emotional damage as one involving Vicodin or vodka. As neurobiological evidence mounts regarding the similarities between all types of addictions, substance or nonsubstance, many are pushing to have the

DSM-IV

category broadened to include them all. One area of focus in better understanding addiction, regardless of its particular basis, is the mesocortical limbic circuitry, including the basal ganglia, and its source of power, the neurotransmitter dopamine.

4

Developing Addiction

Unexpected rewards lead to the release of dopamine in the basal ganglia, which facilitates learning. The more rewarding a particular stimulus may be, the more likely you will be to see an increase in the particular behavior to get it. We often talk about the basal ganglia as the reward system in the mesocortical limbic circuit. Craig Ferris, the Northeastern University researcher who first demonstrated that rats prefer their own pups to cocaine, told me that it pays to be a little more specific when you talk about this particular circuit. “This pathway is not really a reward system per se,” he explained. “It’s more a system for motivation, essentially. It’s involved with evaluating the risks and the rewards involved with certain behaviors, as well as the predictability of things that may come if you engage in a particular behavior.”

Risks

and

rewards: that’s important. Just as no good deed goes unpunished, no good reward—be it sex, food, or potential slot machine payout—comes without some risk. One might argue that risk is what gives a particular behavior that little extra oomph, making it exciting enough to want so badly. The mesocortical

limbic circuit, involving those dopamine-rich basal ganglia, is not just primed to help you get extra food or laid more often. It is attuned to understanding the risks involved with a particular reward and helping you make the right decisions in order to maximize that reward. When that circuit is out of whack, you may end up with an addiction.

5

“Addiction is basically a reward process spinning out of control,” said Schultz. “Not everyone becomes addicted, that is important. We don’t know why some do become addicted and others do not. But in those who do, it’s clear there is some flip in the machinery where you need more of a particular reward than you usually get and can’t properly assess the risks involved with getting it. That flip is linked to the dopamine system in some way, with the release of too much of it into the brain. Ultimately those high levels of dopamine lead to plasticity in the brain, to changes in the reward processing system that result in no longer being able to make sense of the dopamine signals or how they may relate to the outside world in the proper way.”

The long and the short of it is that the reward processing system is compromised by addiction, giving a particular reward a strong value signal, while downplaying the associated risk signal. Over time the compromised reward processing system takes a once positive reward and turns it into a grave negative. Researchers do not know what may cause this wrench in the works (both nature and nurture appear to play a role), but once the switch is thrown, the effects can be devastating.

Love: Addiction’s Blueprint?

Nearly ten years ago Thomas Insel, now the director of the National Institute of Mental Health, published a review paper entitled “Is Social Attachment an Addictive Disorder?” Even before love had been correlated with brain areas in the mesocortical limbic pathway in neuroimaging studies, there was quite a bit of conjecture that social attachments might share a common neural substrate with addiction. Studies in animal models showed strong correlations between the neurobiology of mother-infant attachments and pair-bonds with that of drug addiction—and some have suggested that substance abuse could be an attempt to replace the feel-good chemicals

usually provided to the brain by bonding with others.

6

It’s a compelling idea. After all, it’s hard to make the argument that evolution has naturally selected humans to be susceptible to drug abuse. Instead, perhaps this mesocortical limbic circuit that was developed to promote sex drive and loving attachment was hijacked by drugs, leading to addiction. It’s possible. But does that mean love itself is an addiction too?

“Addiction has a negative connotation. We are too quick to say addiction is always a negative thing, and we don’t know that for certain,” said Schultz. “People who are in love show a number of signs of addiction, including a fascination for a partner, a refocusing of attention, and going to great lengths for a partner. That’s clear. And several studies have now shown that love activates the reward system.” That would be the same reward processing system implicated in drug addiction.

Schultz maintains that it is easy to acknowledge love as a high-value reward. I think most single folks will tell you that attaining a true and loving life partner is high on their list of personal desires. (I also hypothesize that married individuals may tell you frequent, hot sex is even better.) Neither love nor sex is always rewarding. Both have potential negative—even dangerous—consequences. Some consequences are negative enough that, if we gave them full weight in our decisions, we might never bother to have sex or form attachments.

Consider motherhood. Between morning sickness, stretch marks, and labor pain, popping out a kid is far from sunshine and roses, but it is considered one of the most beautiful experiences a woman can have. Any woman with an episiotomy story (and many of us have really good ones) can tell you that. In response to Pilyoung Kim’s fMRI study showing changes to the brain after childbirth, Elizabeth Meyer, a researcher at the University of Richmond, suggested that those brain changes underlie an addiction to motherhood itself. Why is it that women are willing to pop out another kid after the harrowing and painful experience of labor? Perhaps pregnancy and childbirth tweak a mom’s mesocortical limbic system—and with it, her assessment of risks and rewards—so she will focus only on the positive aspects of reproducing and consequently continue birthing those babies.

In an interview

with

Time

magazine, Meyer, who was pregnant with her second child at the time, was quoted as saying, “Being a mom and also being pregnant right now, it’s all very rewarding. If we had to learn from punishing factors, I don’t think we’d do it over and over again. The rewards have to outweigh the punishments.”

7

It is likely that our reward system evolved in such a way to compel us to mate and breed in spite of potential negative consequences, to learn to associate our offspring with good experiences instead of the painful (not to mention fattening) ones. It is a great strategy to promote propagation of the species and the healthy raising of young—not so great when that system is commandeered by a regular coke habit.

8

This evolved system would also have to work its magic on sex and love. It cannot be unique to motherhood; otherwise we would never get to the baby-making portion of the program. We simply cannot afford, from an evolutionary standpoint, to be too put out with a past partner’s piss-poor sexual performance or the end of our previous relationship. Over time it’s the good stuff that stays with us: the anticipatory heat we may have felt before that sexual disappointment; the good times we shared with our exes; the way we feel when we are physically or emotionally touched by another. If it were the bad moments that remained most memorable, we might not get back up on the horse. Our good memories regarding social attachment must carry more weight than the bad. Our mesocortical limbic system is likely making sure of that. A recent study examining the effects of heartbreak on the brain offers some evidence to support this notion.

Breaking Up Is Hard to Do

Love’s more addictive symptoms have a tendency to stick around even if your lover does not. Even after a breakup those in love remain intensely focused (sometimes even more so) on their former partner. The mood swings, obsessive thoughts, personality changes, poor decisions, and lack of self-control also often remain. They may even intensify. The effects of the so-called broken heart are not all that different from the kinds of withdrawal symptoms you may see in a detoxing junkie. Fierce and unrelenting, a lost love can be quite debilitating.

Helen Fisher and her colleagues decided to

use fMRI to look at the brain systems activated after rejection in love. The group recruited ten women and five men who had been rejected in love yet could not quite manage to let go of their intended. More to the point, despite all, they wanted the person who rejected them to come back. These folks reported thinking about their sweetheart more than 85 percent of their waking hours. They also admitted to making inappropriate phone calls or visits to their former love, drinking too much, or sobbing for hours on end. As noted in the study’s report, participants also showed ambivalence and conflicting emotion when it came to their former lover. They believed their love object was their perfect counterpart, yet also expressed great anger and confusion toward their ex about the way things had ended. Basically they all fit the stereotype of that lovesick fool so commonly found in Dumpsville, U.S.A.

Participants were scanned while they looked at a photo of the lover who rejected them as well as one of a familiar yet emotionally neutral acquaintance. Since they demonstrated such strong emotions toward their former sweethearts, they were asked to do a count-back task, wherein they would mentally count back in increments of seven from a random number in the thousands, in between photo viewings, to clear the emotional decks, as it were. While they looked at photos, they were simply asked to think about events they experienced with the person depicted. These instances tended to be emotionally charged with their rejecter, like a last fight or a poignant romantic weekend together, and fairly boring with their casual acquaintance, like watching television together in a dormitory common room.

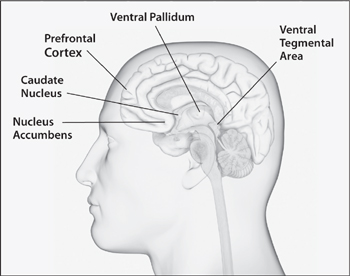

Fisher and her colleagues had several specific hypotheses for this study. The two most important were that they’d see some of the same areas light up as observed in the original love study described in chapter 2, particularly the ventral tegmental area, and that they’d see activation in areas involved with drug craving, such as the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex. Sure enough, that’s what they found. When they compared the results directly to those from the original love study, they found greater activity in the right nucleus accumbens core, ventral putamen, and ventral pallidum than among those happily in love. This, they argue, is evidence to suggest that the romantic drive is a “goal-oriented motivation state” rather than just an emotion, and

a specific form of addiction at that. Just as it brings joy, love can also result in immense sorrow—and even be potentially dangerous.

9

Those rejected in love share patterns of brain activation similar to those who are newly in love as well as to drug addicts. But unlike the other two groups, they also show increased activation in the nucleus accumbens and ventral pallidum.

Illustration by Dorling Kindersley.

Sexual Addiction

Whether or not the idea of love as an addiction seems plausible to you, most agree that sex definitely has the power to make you its slave. Powerful politicians, famous athletes, and everyday Joes have gambled away integrity, position, and family just because they couldn’t resist the siren call of sex. As my friend Kristie can tell you, sexual addiction exacts a hard toll. Work in animal models suggests that certain forms of sexual addiction may be due to problems in the prefrontal cortex.

Lique Coolen, a neuroscientist at the University of Michigan who studies the neurobiology of reward and motivation, was curious about how specific damage to the prefrontal cortex (PFC) may affect sexual behavior, particularly in the areas that link with the mesocortical limbic circuit. She and her colleagues made small lesions in the PFCs of rats, in a specific area that directly connects to the reward circuitry, and then conditioned the rats to associate sex with

illness by injecting them with a drug that made them sick after each copulation session. “We’ve known that the frontal lobe is activated when people are exposed to erotic stimuli for some time,” said Coolen. “But despite knowing it was active in sexual activity, its exact function remained unknown. We thought perhaps it was involved in some sort of inhibitory control.”