Thomas Godfrey (Ed) (8 page)

Read Thomas Godfrey (Ed) Online

Authors: Murder for Christmas

“Yes, sir.”

“Or rather, I fancy, of that goose.

It was one bird, I imagine, in which you were interested—white, with a black

bar across the tail.”

Ryder quivered with emotion. “Oh,

sir,” he cried, “can you tell me where it went to?”

“It came here.”

“Here?”

“Yes. and a most remarkable bird it

proved. I don’t wonder that you should take an interest in it. It laid an egg

after it was dead—the bonniest, brightest little blue egg that ever was seen. I

have it here in my museum.”

Our visitor staggered to his feet

and clutched the mantelpiece with his right hand. Holmes unlocked his strongbox

and held up the blue carbuncle, which shone out like a star, with a cold,

brilliant, many-pointed radiance. Ryder stood glaring with a drawn face,

uncertain whether to claim or to disown it.

“The game’s up, Ryder,” said Holmes

quietly. “Hold up, man, or you’ll be into the fire! Give him an arm back into

his chair, Watson. He’s not got blood enough to go in for felony with impunity.

Give him a dash of brandy. So! Now he looks a little more human. What a shrimp

it is, to be sure!”

For a moment he had staggered and

nearly fallen, but the brandy brought a tinge of colour into his cheeks, and he

sat staring with frightened eyes at his accuser.

“I have almost every link in my

hands, and all the proofs which I could possibly need, so there is little which

you need tell me. Still, that little may as well be cleared up to make the case

complete. You had heard, Ryder, of this blue stone of the Countess of Morcar’s?

“It was Catherine Cusack who told me

of it.” said he in a crackling voice.

“I see—her ladyship’s waiting-maid.

Well, the temptation of sudden wealth so easily acquired was too much for you,

as it has been for better men before you; but you were not very scrupulous in

the means you used. It seems to me, Ryder, that there is the making of a very

pretty villain in you. You knew that this man Horner, the plumber, had been concerned

in some such matter before, and that suspicion would rest the more readily upon

him. What did you do, then? You made some small job in my lady’s room—you and

your confederate Cusack—and you managed that he should be the man sent for.

Then, when he had left, you rifled the jewel-case, raised the alarm, and had

this unfortunate man arrested. You then—”

Ryder threw himself down suddenly

upon the rug and clutched at my companion’s knee. “For God’s sake, have mercy!”

he shrieked. “Think of my father! of my mother! It would break their hearts. I

never went wrong before! I never will again. I swear it. I’ll swear it on a

Bible. Oh, don’t bring it into court! For Christ’s sake, don’t!”

“Get back into your chair!” said

Holmes sternly. “It is very well to cringe and crawl now, but you thought

little enough of this poor Horner in the dock for a crime of which he knew

nothing.”

“I will fly, Mr. Holmes. I will

leave the country, sir. Then the charge against him will break down.”

“Hum! We will talk about that. And

now let us hear a true account of the next act. How came the stone into the

goose, and how came the goose into the open market? Tell us the truth, for

there lies your only hope of safety.”

Ryder passed his tongue over his

parched lips. “I will tell you it just as it happened, sir,” said he. “When

Horner had been arrested, it seemed to me that it would be best for me to get

away with the stone at once, for I did not know at what moment the police might

not take it into their heads to search me and my room. There was no place about

the hotel where it would be safe. I went out, as if on some commission, and I

made for my sister’s house. She had married a man named Oakshott, and lived in

Brixton Road, where she fattened fowls for the market. All the way there every

man I met seemed to me to be a policeman or a detective: and, for all that it

was a cold night, the sweat was pouring down my face before I came to the

Brixton Road. My sister asked me what was the matter, and why I was so pale;

but I told her that I had been upset by the jewel robbery at the hotel. Then I

went into the back yard and smoked a pipe, and wondered what it would be best

to do.”

“I had a friend once called

Maudsley, who went to the bad, and has just been serving his time in

Pentonville. One day he had met me, and fell into talk about the ways of

thieves, and how they could get rid of what they stole. I knew that he would be

true to me, for I knew one or two things about him; so I made up my mind to go

right on to Kilburn, where he lived, and take him into my confidence. He would

show me how to turn the stone into money. But how to get to him in safety? I

thought of the agonies I had gone through in coming from the hotel. I might at

any moment be seized and searched, and there would be the stone in my waistcoat

pocket. I was leaning against the wall at the time and looking at the geese

which were waddling about round my feet, and suddenly an idea came into my head

which showed me how I could beat the best detective that ever lived.”

“My sister had told me some weeks

before that I might have the pick of her geese for a Christmas present, and I

knew that she was always as good as her word. I would take my goose now, and in

it I would carry my stone to Kilburn. There was a little shed in the yard, and

behind this I drove one of the birds—a fine big one, white, with a barred tail.

I caught it, and, prying its bill open, I thrust the stone down its throat as

far as my finger could reach. The bird gave a gulp, and I felt the stone pass

along its gullet and down into its crop. But the creature flapped and

struggled, and out came my sister to know what was the matter. As I turned to

speak to her the brute broke loose and fluttered off among the others.”

‘Whatever were you doing with that

bird. Jem?’ says she.

‘Well.’ said I, ‘you said you’d give

me one for Christmas, and I was feeling which was the fattest.’

‘Oh,’ says she, ‘we’ve set yours

aside for you—Jem’s bird, we call it. It’s the big white one over yonder. There’s

twenty-six of them, which makes one for you, and one for us, and two dozen for

the market.’

‘Thank you, Maggie,’ says I; ‘but if

it is all the same to you, I’d rather have that one I was handling just now.’

‘The other is a good three pound

heavier,’ said she, ‘and we fattened it expressly for you.’

‘Never mind. I’ll have the other,

and I’ll take it now,’ said I.

‘Oh. just as you like.’ said she, a

little huffed. ‘Which is it you want, then?’

‘That white one with the barred

tail, right in the middle of the flock.’

‘Oh. very well. Kill it and take it

with you.’

“Well, I did what she said, Mr.

Holmes, and I carried the bird all the way to Kilburn. I told my pal what I had

done, for he was a man that it was easy to tell a thing like that to. He

laughed until he choked, and we got a knife and opened the goose. My heart

turned to water, for there was no sign of the stone, and I knew that some

terrible mistake had occurred. I left the bird, rushed back to my sister’s, and

hurried into the back yard. There was not a bird to be seen there.”

‘Where are they all, Maggie?’ I

cried.

‘Gone to the dealer’s, Jem.’

‘Which dealer’s?’

‘Breckinridge, of Covent Garden.’

‘But was there another with a barred

tail?’ I asked, ‘the same as the one I chose?’

‘Yes, Jem; there were two

barred-tailed ones, and I could never tell them apart.’

“Well, then, of course I saw it all,

and I ran off as hard as my feet would carry me to this man Breckinridge; but

he had sold the lot at once, and not one word would he tell me as to where they

had gone. You heard him yourselves tonight. Well, he has always answered me

like that. My sister thinks that I am going mad. Sometimes I think that I am

myself. And now—and now I am myself a branded thief, without ever having

touched the wealth for which I sold my character. God help me! God help me!” He

burst into convulsive sobbing, with his face buried in his hands.

There was a long silence, broken

only by his heavy breathing, and by the measured tapping of Sherlock Holmes’s

finger-tips upon the edge of the table. Then my friend rose and threw open the

door.

“Get out!” said he.

“What, sir! Oh, Heaven bless you!”

“No more words. Get out!”

And no more words were needed. There

was a rush, a clatter upon the stairs, the bang of a door, and the crisp rattle

of running footfalls from the street.

“After all, Watson,” said Holmes,

reaching up his hand for his clay pipe, “I am not retained by the police to

supply their deficiencies. If Horner were in danger it would be another thing;

but this fellow will not appear against him, and the case must collapse. I

suppose that I am commuting a felony, but it is just possible that I am saving

a soul. This fellow will not go wrong again; he is too terribly frightened.

Send him to jail now, and you make him a jail-bird for life. Besides, it is the

season of forgiveness. Chance has put in our way a most singular and whimsical

problem, and its solution is its own reward. If you will have the goodness to

touch the bell, Doctor, we will begin another investigation, in which, also, a

bird will be the chief feature.”

“I’ve just told Fettle

about the will.

Like so many Americans, my sole

acquaintance with wassail was through the song “Wassail, Wassail, all over the

town,” and occasional mention of a wassail bowl. As neither my parents nor

their friends seemed to partake of wassail at Christmas, I came to suspect it

was either lewd, illegal, or at the very least, unsanitary.

Egg Nog was always the drink on hand

at Christmastime. Although there might be some dispute as to whether it should

be spiked with rum or brandy, there was always a dash of nutmeg on top to give

it some spice.

I have since read of a lady in

Brixton who added ground glass to her nogs to give them some tang, but I think

this is generally to be avoided, unless you have a limited amount and wish to

discourage seconds.

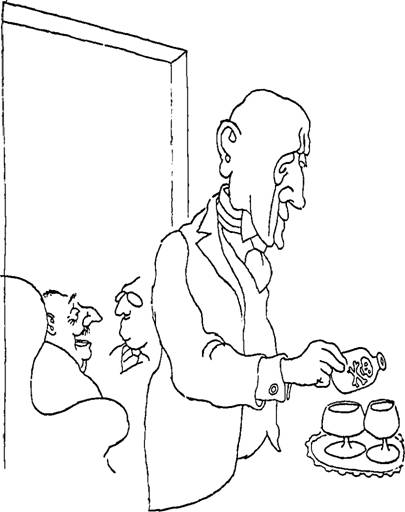

The gentleman pictured discovered

that an extract of mistletoe berries gave egg nog a certain festive quality. So

successful was his recipe, that he was persuaded to enter it in a Festival of

Britain Cookery competition where he was given first prize and ‘the Chair.’

-

Agatha Christie

Her heroes were an eccentric windbag

and a meddlesome old lady. Her writing seldom got more violent than a good bump

on the head. She was hopelessly unconvincing describing anyone under thirty.

And her approach to sex and passion was that of two arthritic porcupines

mating. Yet she was the most successful author of mystery stories that the

world has yet produced.

What made Agatha Christie the

writing phenomenon of her time? Plotting. No one could wring as many

possibilities out of a murder as she. And, because she couched them all in

cozy, English gentility, she caught her reader napping, more often than not.

When “The Adventure of the Christmas

Pudding” (also called “The Theft of the Royal Ruby”) was first collected, she

included an introductory memoir. The story, prefaced by her remarks, begins on

the next page.