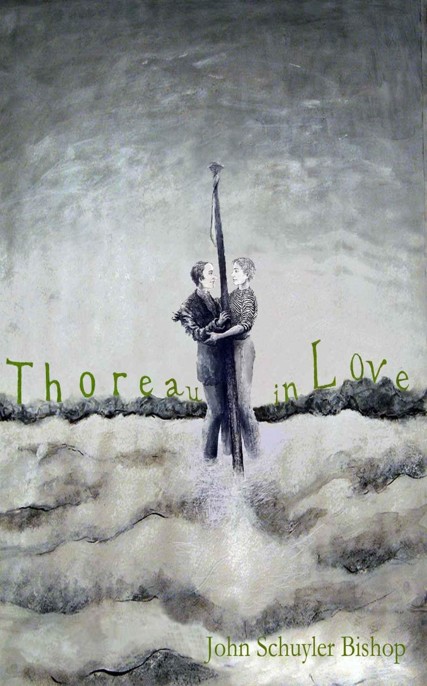

Thoreau in Love

Authors: John Schuyler Bishop

ISBN: 9781626758063

For Bryan Byers, who I realized too late

was forever and always the object of my desires

Foreword

In 1843, Henry David Thoreau left Concord, Massachusetts, with no thought of ever returning. His destination was New York, to tutor the children of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s eldest brother. Years before, Thoreau began keeping what became a lifelong journal of his thoughts and observations, but for the time he spent in New York, some 250 pages have been torn out and lost, the only substantial number of pages missing from his journals

.

At Sea

1

Bundled against the chilly spring wind, Henry David Thoreau held tight to the gunwale as he leaned over

Dahlia

’s worn bow to watch splash after brilliant splash thrown off onto the ice-blue sea. Though the wind roared, his ears ached and his stomach churned, he thrilled in his new state. “I am at sea!” A spray of salt water spattered him, but, undeterred, he shook off the cold and wiped his face. To be daring, he inched out over the bowsprit. The schooner’s bow dipped, then rose high on a wave, higher than Henry wanted to go. He scrambled back and wedged himself into the crook of the bow, and as

Dahlia

plunged into the trough, he watched in amazement as plumes of icy white water shot into the air. “At sea,” he said. “Literally and figuratively. But finally away from that stifling small town!”

Henry was 25 years old and on his way to New York, where everything was new, where everything that was America was exploding with volcanic excitement, where he would make his career in publishing. It was early May, 1843, and as far as Henry was concerned, that morning he’d seen the last of Concord, Massachusetts.

Up before dawn, Henry had tried to tell himself the day was like any other, but he was so excited about starting his adventure that, pulling on his trousers, he lost his balance and, one leg in, one leg caught, he hopped laughingly around the bare attic floor until his sister Helen called up asking, “Henry? Are you all right?”

“I’m fine,” he said and fell back onto his bed. “I just can’t get my legs to do what they should.”

“You have a schedule to keep. If you miss the morning stage, Mrs. Emerson will leave without you. And you must eat some breakfast.”

“I shall be down in a minute.” Henry lay on his back and looked up at the peaked ceiling. “And then I’ll be gone.” Turning his head, he took in his room: the desk where he’d spent so much time writing; the gabled window he’d gazed out for hours; the yellow-washed wallboards he and his brother, John, had painted. “What a mess we made.” And, of course, John’s empty bed. Henry let out a breath, sat up and caught his reflection in the mirror.

Most of the time when Henry saw his face he thought, Ugly egg. But today was different. Quietly, he said, “I look good.” With his fingers he combed his wavy brown hair over his ears and across his high forehead. He turned a bit to the side, better to see the droop of his long nose, which John loved to tease him about. “Even if my nose does look like my penis.” And his chin, which John said looked like a baby’s bottom in miniature. “Time to get these stumps atrot.” He grabbed his stuffed duffel bag. To the room, he said, “Good-bye, my friend, my attic aerie.” And to the empty bed: “Good-bye, John, my Indian guide.”

At breakfast, listening to his mother and his sisters all laughing and talking too much, Henry thought, This might be the last time I hear my mother’s voice. As the melancholy washed over him he sank in his chair.

“Don’t get sad now, Henry,” said his mother.

“No, no, I’m fine,” he said, forcing a smile. For a moment everyone at the table became quiet, then Helen, using her know-it-all, bossy voice, said, “Eat your porridge, Henry.” Henry smiled wanly, lifted his spoon and said, “What will you do when you can’t tell me what to do?”

“Boss me around,” said little Sophia, “the way she always does.” Even their father laughed, but it was nervous, pained laughter, and Henry knew, like him, they were thinking about John, who’d died of lockjaw the year before. “Don’t worry, Helen,” said Henry, “you’ll always be able to boss me around.”

“Wooo-wooo,” said Sophia, waving her fingers, pretending to be a spooky ghost. “And how will she do that, Transcendentally?” Everyone laughed and relaxed.

His mother said, “I don’t know who’ll do your laundry. Certainly not Mrs. Emerson.”

“I shall have to learn to do it myself.”

“That’ll be the day,” said Sophia. Their father then pushed out his chair, saying, “I nearly forgot, I have something for you.” As he shuffled back to his workroom, Sophia said, “I know what it is.”

“Don’t tell,” said Helen. Henry’s father returned with his hands behind his back. Henry rose from his chair. “What is it, Pa?”

“Close your eyes.” Henry did, and his father held before him a bundle of twelve lead pencils, tied with a ribbon. Henry’s father was one of only five pencil makers in the Boston area; though his pencils were much more expensive than Joseph Dixon’s machine-made pencils—and not nearly as good—his were made with love. Henry’s sisters and mother oohed and aahed, and then his father said, “All right, you can open them.”

Henry couldn’t believe his eyes. “No, Dad, I can’t. I know how long they took you to make.”

Though Henry protested, he was used to being spoiled by his family. His mother cleaned his room and did all his laundry, and even when they’d had no money at all, Helen and John had taken jobs so Henry could attend Harvard. Without undoing the ribbon, he examined the pencils. “They’re beautiful.”

“They’re my best work,” said his father. “I made them for you, for your writing career, with the thought that you’ll write good words with them.”

In a rare moment of spontaneous emotion, Henry took his father by the arms. Tears dribbled down everyone’s cheeks, but then breaths were drawn as everyone realized it was time for Henry to go.

The air was crisp, and as the Thoreaus huddled by the Concord Stage depot, sobriety prevailed until they saw the eastbound stage approaching and, from the north, running full-tilt, calling Henry’s name, Ellery Channing.

“Look out,” said Sophia. “It’s that crazy fool Ellery Channing.” Henry beamed. The stagecoach driver pulled up his horses just as Ellery tripped and fell into Henry, grabbing him to keep himself from falling. Sophia laughed and said, “Ellery, you’re mad.”

In just three months, Ellery had earned the reputation of being the oddest young man in Concord, more peculiar even than Henry. Though Henry was fond of Ellery, he was also afraid of him. He and Ellery had a bit of history, from their days at Harvard, and when he heard Ellery and his wife were moving to Concord, Henry knew it was so Ellery could be near him. And didn’t Ellery prove Henry right when, three weeks after their arrival, he moved out on his wife and wanted nothing more to do with her—and everything to do with Henry. Ellery always wanted more. It was in his every look, his every gesture. For Ellery, it was never enough to be just friends. Henry was glad to be putting distance between them.

Still holding on to Henry, Ellery said, “I was afraid I wouldn’t make it. Mrs. Thoreau, Mr. Thoreau. Girls.”

“You shouldn’t have come,” said Henry.

“And not see my dear friend off?”

The stationmaster announced the eastbound coach.

“Here I go,” said Henry.

“You’re going to grind them up, Henry!” said Ellery.

The stationmaster, assessing Henry’s height, offered him the use of the ladies’ steps. Scowling, Henry took a giant step up to the twelve-passenger stagecoach, reached only air and stumbled. “Good start!” said Ellery. Sophia snickered; then everyone laughed and Henry awkwardly climbed aboard. Once more the stationmaster called, “Eastbound stage,” and Henry, feeling guilt about being so excited to leave, leaned out his window and said, “Why am I going east? I thought New York was west of here.”

“You’re always going the wrong way, Henry,” said Ellery. “Take care. I’ll miss you.”

The stagecoach jerked into motion, and as it picked up speed, everyone waved and called their goodbyes. Disappointed that the Emersons hadn’t come to see him off, Henry sat back. Soon, though, the horses broke stride, and Henry, hoping he knew why they were slowing, looked out and saw, standing in the road, the handsome, renowned, 40-year-old Ralph Waldo Emerson. “Waldo!”

In a landscape of luminaries, Waldo was the golden glow, the sun and the moon. Because of him the great thinkers and writers of America descended on Concord, not to pay their respects, but to argue and theorize and dream. At Waldo’s house, everything that wasn’t supposed to be spoken about in polite conversation was heatedly debated: religion and politics, love, even sex. Did masturbation drive people insane? Were women equal to men? Was there life after death? Was the abolition of slavery fair to the South? They discussed the classics, Roman and Greek, the Romantic poets, industrialization, the flood tide of Irish immigrants. Was anything worthwhile? Did God exist in the lowly worm? Did God even exist? Was there an actual American spirit? Was everyone somehow connected, a part of the same life of the mind? Was a shared life the ideal, or was the individual all that mattered? What role did the senses play? When those topics were exhausted, they raised their voices in favor of or against Brook Farm, the communal living experiment, and those tawdry, sensational penny newspapers everyone read. Did American publishers care only about British authors, whose work they freely stole? Were railroads, one being built even to Concord, harbingers of great things to come or merely noisy, dangerous, cinder-spewing incursions? No matter who was in attendance, Waldo made sure to include his gray-eyed young friend with the brown curls covering his high forehead.

Henry loved being part of this new movement of American thinkers who questioned every institution, so much so that many of Waldo’s admirers wondered why Henry would ever want to leave Concord. But Henry knew he had to get away; there was something pulling him, a terrifying force he couldn’t put words to, whose tug was ferocious. Waldo understood, but then Waldo understood everything—even that his own wife, Lidian, had become an albatross around Henry’s neck.

As the stage slowed to a halt, Lidian, lifting her long gray skirts, burst out the front door of their house and hurried down the path. Standing on the carriage stone, she reached into the coach, kissing and hugging Henry, pleading through tears, “Henry, don’t go, please don’t go.”

Thankfully for Henry, the driver said, “Come along, Mr. Emerson, I’ve a schedule to keep.”

“Just a moment, Tom,” said Waldo, firmly holding his wife. “Lidian, let Henry alone.” Then: “Here’s a package I want you to deliver to Giles Waldo, that young man I told you about. Godspeed, my friend. Write to me.”

Henry waved to his adoring friends until they were out of sight, then he sank into his seat and sighed, feeling for once not like a son but a grown man. Behind him in the coach two men engaged in a conversation about commerce. The commerce of the world. The world Henry was on his way to join. “You wait,” said one. “Morse’s telegraph will change the world.”

“Bah,” said the other. “It’s a waste of our taxes. Leave business to the businessmen. Harden Express can deliver me a letter or a package before ten men could decipher that code. Are they going to be able to send packages over those wires?” The two men talked and talked, as if they alone knew the secrets of trade, stopping only when a rutty bump tossed the passengers and made them laugh or cuss. Jolted out of his stupor, Henry took hold of the window frame to steady his gaze as the spring green countryside he knew so well scrolled by. Often when Henry was alone with his thoughts, he whistled or unconsciously sang softly what was going on in his mind; this morning, on the way to a new life, the song was “Old Rosin the Beau”: