Thoreau's Legacy (6 page)

Authors: Richard Hayes

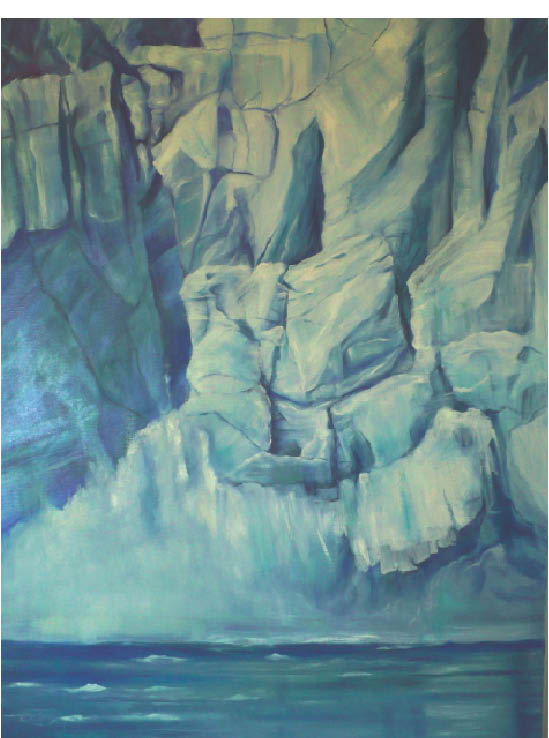

Calving

Tidewater Glacier

Trude McDermott

My perceptions as a working artist are strongly influenced by the changing landscape. In the last few years I have tried to capture

the complexity and beauty

of these receding icy giants, visual reminders that we humans must align ourselves with the balance of the natural world.

Trude McDermott

has been a painter and mixed- media artist for the past twenty-five years. She lives with

her husband in Coarsegold, California, near Yosemite National Park.

In Defense of Ice

Carol Ellis

HAVING BACKPACKED ALL MY LIFE, I AM BOUND TO

ice and glaciers over rivers of time. Today I see clearly how global warming threatens them. My connection to Glacier National Park began in the summer of 1966. On my days off from work, I hiked hundreds of miles, past Blackfoot Glacier, up to Sperry Glacier, and over Siyeh Pass with its three glaciers. At Grinnell Glacier

my friends and I jumped crevasses, glancing

down the yawning cuts

into blue ice.

We climbed along the bottom edge of a snow field, trying to reach the western slope of Salamander Glacier, which lies cradled in the sheer crest of Mount Gould. The rugged terrain stopped us.

In 1971 my husband and I packed our young daughter along the Continental Divide on the back side of the mountain wall, where we scrambled up the notch to look down on Grinnell. From that elevation the glacier looked grayer than I remembered—perhaps because the sky was overcast, I thought. But in 1987, when we hiked from Swiftcurrent Valley toward Grinnell and Salamander, I was shocked. In twenty-one years Salamander Glacier had visibly shrunk. The tail had atrophied, the neck was strangled, the head was more diminutive, the belly had tucked and flattened up toward the spine. Grinnell had also changed. Its contracted surface area looked dirtier and grayer from the melting that had occurred. Many more rocks lay on the surface, as in the Himalayas today. The National Park Service had cordoned off more areas of instability. Where in 1966 we had hopped crevasses and hiked closer to the Salamander, now visitors walked with a ranger. And in 2000, when I crossed over Gunsight Pass past Blackfoot Glacier, I saw that same kind of assault on the compressed ice of the glacier’s core.

If I want to confirm that rising temperatures threaten the glaciers, I can look at the winter ice on Waitts Lake in Washington, where I have a cabin. The omens in the ice are grim. Waitts Lake freezes later and melts earlier, often turning into pools of mush rather than thick, jagged icebergs, as it used to in the 1970s. The warm water in the pools drizzles through the mass of ice and softens it. Forty years ago, as fishing season approached toward the end of April, we’d wonder if the ice would clear. We’d sled or skate our children across the lake in January with no qualms. In February we could still hear the ice whoop as it split to allow more freezing. But by the late ’80s the ice was usually gone in March, and by the ’90s sometimes sooner. Rarely can the ice bear the weight of walkers or snowmobiles as it used to. Also the lake temperatures have risen; swimming season lasts one month longer than it did in the ’70s.

As the winters get shorter and the grasses green earlier, the deer multiply. The blackbirds chortle in the cattails sooner. We entertain more clouds of midges in May. Long V’s of Canada geese honk their way south even in December. Both wildlife and humans have changed their patterns.

All life flows with the cycles of water. I fear my grandchildren will not be able to enjoy glaciers in Glacier Park or whooping ice at Waitts Lake. I watch warily as we approach the tipping point for saving glaciers, ice, and life on this blue planet.

Carol Ellis

has taught first grade in Spokane, Washington, for over twenty-five years. She raised her own three children to hike, swim, and skate at Waitts Lake.

Disappearing Coral

Craig Quirolo

In 1993 during a Reef Relief Photo Monitoring Survey dive, yellow-band disease was discovered and documented for the first time (top). Coral bleaching is often associated with rising ocean temperatures (middle).

A five-hundred-year-old coral

has died in a single decade (bottom). It would be a shame if the first generation of divers turned out to be the last to see living coral.

Craig Quirolo,

a photographer and artist who founded the environmental group Reef Relief in 1985.

He lives in Brooksville, Florida.

Disappearing coral, Key West, Florida. Photos by Craig Quirolo.

Change Is in the Air

Kristan Hutchison

A FAMILIAR STENCH BLEW ACROSS THE ARCTIC TUNDRA. My three fellow hikers wrinkled their noses while I looked around with uneasy recognition.

In our travels north of the Arctic Circle on a journalism fellowship to learn about research in Alaska, we had smelled little but dry lichen and the occasional plume of diesel and dust from trucks headed to oil fields at Prudhoe Bay.

This new odor reeked of

grass clippings and coffee grounds

rotting in a swamp.

I scanned the ground and horizon for its source, expecting to find moist piles of manure and a few heifers chewing their cud.

This was a smell I remembered from my childhood thirty years ago and 2,780 kilometers south, in the cow pastures of our family farm near Seattle. The moist odor carried memories of idyllic summer afternoons, splashing in a creek as cow pies oozed into the mud and crusted in the sun. But here on Alaska’s North Slope there were no cows, no alders leaning over lazy streams, no snakes to catch in the grass.

Except for the Brooks Range to the south, the tundra was so flat and empty I could see the curve of the earth as it stretched toward the Arctic Ocean. Caribou and musk ox grazed these lands rather than cattle, but I saw no sign of them. Here the smell of manure was as disconcerting as if one of the bearded scientists had suddenly spoken to me in my mother’s voice.

Seeing where the smell originated intensified my unease. As we walked, a crevice appeared a few yards ahead. The top layer was like a green skin protecting the permafrost below. Now, a few weeks into summer, the skin had cracked open, exposing mud and shards of ice. Dinosaur dung, mastodon manure, and other organic materials that had been trapped in the frozen ground for thousands of years were suddenly exposed to the relentless Arctic sun. The result was just like leaving a freezer door ajar so the food melts and rots. What I smelled was probably hydrogen sulfide gas released from the tundra. Even more disconcerting was what I couldn’t smell: the methane and carbon dioxide rising from the melting permafrost into the atmosphere, adding to the layer of gases that cause global warming.

Poised at the edge of the fresh crevice, I could hear a trickle of water coming from the ground below. The ice was melting into a rank river, like the muddy brook I played in as a child, carving a streambed through half a mile of tundra. What had been frozen was now flowing freely to the sea, ready to add to already rising waters.

Over the past several years I had interviewed scientists about climate change and studied their projections. I knew how high the oceans had already risen. I’d seen the shrinking glaciers. But when I saw the tundra cracks of global warming, what I’d known intellectually punched me in the gut. We have opened a door that will be difficult to close again, because it has set off a cycle of its own. Now, whenever I bring home a bag of manure to fertilize my garden, I’m not comforted by childhood memories but alarmed by the whiff of global warming.

Kristan Hutchison

has worked as a reporter and editor for over twenty years, most of that time in Alaska.