Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig (42 page)

Read Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig Online

Authors: Oliver Matuschek

19

28th November 1931, Zweig GW Tagebücher, p 357.

20

Stefan to Alfred Zweig, undated, probably 28th November 1931. In: Briefe III, p 310 f.

21

Hinterberger 1952, p 46.

22

Ebermayer 2005, p 200.

23

Friderike to Stefan Zweig, 16th January 1932. In: Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 2006, p 252 ff.

24

Stefan to Friderike Zweig, undated, probably 13th February 1932. In: Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 2006, p 256.

25

Völkischer Beobachter 1932.

26

An die Freunde im Fremdland. In: Zweig GW Schlaflose Welt, p 42 ff.

27

Stefan Zweig to Richard Schaukal, undated, probably mid-May 1914, WSLB Vienna, HIN 224.981.

28

Stefan to Friderike Zweig, 9th March 1933. In: Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 2006, p 267 f.

29

Stefan Zweig to Karl Geigy-Hagenbach, 20th March 1933, ÖUB Basle.

30

Davies/Fichtner 2006, No 3712.

31

Stefan Zweig to Karl Geigy-Hagenbach, 2nd September 1933, ÖUB Basle.

32

Stefan Zweig to Karl Geigy-Hagenbach, 2nd September 1933, ÖUB Basle.

33

Stefan Zweig to Karl Geigy-Hagenbach, 25th October 1933, ÖUB Basle.

34

Stefan Zweig to Klaus Mann, 18th November 1933. In: Briefe IV, p 73.

35

Letter from the Association of German Booksellers to Insel Verlag, 27th November 1933, GSA Weimar, 50/12.

36

Anton Kippenberg to the Reich Ministry for Public Education and Propaganda, 3rd December 1933 [?],GSA Weimar, 50/12.

37

Zweig GW Welt von Gestern, p 440 f.

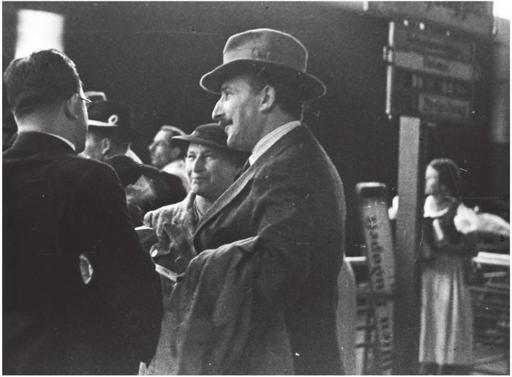

Friderike and Stefan Zweig at the main railway station in Salzburg

I’m leaving my house, of course. It’s all over now. As you know, I wanted to leave before this, but I kept on backing off so as not to send any signals. The captain should be the last one to leave the sinking ship. But this insult from these stupid policemen, this moral slap in the face, has legitimised my decision. To be honest, I welcome this insult. It has helped me make up my mind.

1

To Romain Rolland 25th February 1934

N

EEDLESS TO SAY, THE

house search in Salzburg had not been ordered by chance. When Zweig had stopped off for a few days in Vienna on his way back from London in February, he found what was effectively a civil war going on. Here as in other Austrian cities, the extreme right-wing Home Guard, which supported the government of Federal Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss, was fighting in the streets with supporters of the banned Republikanischer Schutzbund, the paramilitary wing of the Social Democratic party. Hundreds of people were killed. Against the background of these events, the attempt by conservative and anti-Semitic groups to smear Zweig with the accusation that he had helped the Schutzbund by hiding weapons in his house had achieved the desired effect. However firm Zweig’s decision to leave Salzburg had been when he arrived back in Austria, in the wake of this provocation it was irrevocable. He acted accordingly, not only asking his brother Alfred to deregister him in his former place of residence, but also instructing a solicitor to have his name removed from the register of taxpayers. He even cancelled his membership of the Goethe Society after paying his annual dues for the past year, since he planned to give up his library—as he informed his secretary. She was also given the task of destroying the entire correspondence relating to his lecture tours in Germany—all that was a closed chapter for him now.

By now Zweig was back in the flat in Portland Place, where he soon had to contend with fresh accusations. The Austrian embassy in Paris had sent a report to the Federal Chancellery in Vienna, alleging that during his last stay in Paris as well as in London Zweig had been spreading propaganda against his native country at a series of closed meetings and on other occasions. The Austrian ambassador in London, instructed

by his superiors to take immediate action to counter Zweig’s influence, could only report that there was no evidence of such activities, and that he, Zweig, had merely made a speech at a dinner hosted by the banker Rothschild at his London home in November 1933. And the speech in question did not even mention Austria. Zweig had been addressing very different problems that evening, making an urgent appeal for the organisation of extensive humanitarian aid for Jewish children in Germany. At the time he regarded this as a top-priority issue. Once the ambassador had reported back from London, the agitation in diplomatic circles appeared to diminish. But Zweig learnt of these allegations against his person and felt confirmed once again in his dark forebodings.

At least he had come up with a rather elegant solution to the problem of finding a new publisher after the break with Insel. The Viennese publisher Herbert Reichner, with whom Zweig had already collaborated, notably in the matter of the Mozart facsimile letter, agreed to take on his future works. It was comforting to know that his books would be printed here to the same high standards of design and production for which Insel Verlag was renowned. In addition he had been able to secure an editorial position with Reichner for his old friend and chess partner, Emil Fuchs, whose previous job with the Social Democratic paper

Salzburger Wacht

had disappeared when the party itself was banned. It also meant that Zweig now had his own man on the inside at the new publishing house.

The book on Erasmus of Rotterdam was Zweig’s first work to appear under the Reichner imprint after the split from Insel. Despite all the threats and restrictions, his books continued to be distributed and sold in Germany until the early months of 1936. Only then was a complete ban on sales imposed, limiting the primary market for the German-language editions of his works to Austria and Switzerland.

According to the title pages of its books, Zweig’s new publisher had offices in Vienna, Leipzig and Zurich, but in Germany and Switzerland the imprint was simply represented by commission agents; the management and other staff were all based in Vienna. In a sense ‘Stefan Zweig plc’ now had three branches too—in Salzburg, London and Vienna. To begin with it had not been easy to coordinate work in his former home, where all his records and files were kept, collaboration with his publisher in Vienna and the production of new texts in London (or wherever Zweig happened to be doing his writing). His secretary Anna Meingast continued to work in the house at Kapuzinerberg 5, and the correspondence between her and

the ‘Herr Doktor’ relating to administrative matters grew steadily more voluminous under Friderike’s watchful eye. Zweig soon became intimately acquainted with the rail journey from London to Vienna and back via Paris, Zurich and Salzburg, a route chosen to give Germany a wide berth.

Friderike had followed Stefan to London shortly before Easter 1934. For one thing she wanted to help him decorate his furnished flat. But she also seems to have harboured hopes of persuading him to return to Salzburg—which she signally failed to do. One thing was certain—if he was to carry on working in London under these fraught conditions, he would need another secretary to assist him there. So enquiries were made at Woburn House, where the aid organisation for Jewish refugees was based—was there a suitable lady candidate for this secretarial post among the immigrants from Germany? The key requirements were perfect German, written and spoken, a command of French, and of course English, as it was clear that Zweig would soon be conducting more business with British and American correspondents. Evidence suggests that the recommendation of Elisabet Charlotte Altmann for the post came through friends in Vienna. Lotte or Liselotte Altmann, as she preferred to call herself, had been born on 5th May 1908, the daughter of an ironmonger in Kattowitz, and had originally planned to study in Germany—but had not been allowed to do so because she was Jewish. She had then travelled to London, where her brother Manfred was already living with his wife Hannah and other relatives.

Friderike had carefully vetted all the applicants for the post of secretary and had been closely involved in the final decision. In her memoirs she recalls Lotte as a single woman who had just then turned twenty-six, whom she describes as

a very serious, not to say melancholy girl, who looked the very embodiment of the fate that had befallen her and so many fellow sufferers. [ … ] Physically the young secretary cut a rather frail figure, there was something about her of those timid, wilting creatures that Dostoevsky describes so vividly. But she overcame her frailty with admirable energy. She had already demonstrated her tireless diligence and her particular aptitude when we learnt that she had suffered from asthma since her childhood, and had tried assorted cures without success.

2

These sentences, written by Friderike years later, could be describing an anti-heroine to her own self—which had probably been her intention, as will become clear in the light of later events.

There is no doubt that the Zweigs’ marriage was in crisis. Friderike was only too well aware that Stefan’s decision to take a small flat in London could be the beginning of the end for their life on the Kapuzinerberg. They went down to Dorset for a few days in the country, and Friderike tried again to dissuade her husband from his decision. To no avail. A return to his former life was completely out of the question for Stefan, given the growing threats from Germany and within Austria itself, the sorry state of their marriage and the situation with Friderike’s daughters.

Many things point to the fact that Zweig was looking for a change of direction in his life, his manuscript collection being one such indicator. He had added to it very little in 1933 and 1934, even declining the purchase of a viola that had belonged to Mozart. While his future place of residence remained in doubt, he did not wish to burden himself with further acquisitions. At times he even thought about disposing of the collection. One of the few new acquisitions during this period deserves a special mention, however. In August 1933, in conditions of the strictest secrecy, Zweig bought a thirteen-page manuscript of one of Adolf Hitler’s speeches. At first glance this would seem to be an astonishing purchase; and yet, bizarrely enough, it makes perfect sense in terms of Zweig’s motivation for buying manuscripts in the past. Just as he had sought to get closer to the giants of literature and music through their manuscripts, so he was evidently now hoping to find the key to Hitler’s personality, at least in part, in the same time-honoured fashion. Zweig had had to get used to the fact that his friends and acquaintances had very little time for this quasi-mystical approach of his, even in the case of “ordinary” manuscripts. Not least for this reason he told nobody about his new acquisition in this special instance, and got the antiquarian book dealer in Berlin who had arranged the purchase, Hellmut Meyer & Ernst, to confirm in writing that he was the rightful owner of the piece.

While negotiating the purchase of the Hitler manuscript he continued to work on his

Erasmus

, a book that would have a far greater personal significance for him than any of his works had done for a long time. Shortly before completing his labours he wrote to his Italian translator, Lavinia Mazzucchetti: “

Erasmus

has been a great help to me, just as

Jeremias

was during the war. It has become a kind of ‘helper in time of need’, enabling me to clarify many things in my own mind. If one studies history a good deal in these times, one also gains a better perspective on the present; I have no intention of allowing myself to be forced into a fruitless opposition

to events of the day, or to be browbeaten by others into believing that the Jewish problem is the most important, indeed the only question in life.”

3

All the same, Zweig could not avoid speaking out constantly on this issue. His response to a survey on Jewish literature showed that his opinion on the subject remained largely unchanged—Jewish writers, he believed, should not isolate themselves from the literary mainstream, but at this particular time they were under very great moral pressure, which would amplify their sense of responsibility. Zweig expressed the hope that the quality of their books would improve, since it was not enough now to produce entertainment that sold well: writers had to engage with the issues of the day. He himself had succeeded in this with his

Erasmus

, as colleagues such as Joseph Roth and Thomas Mann had acknowledged in appreciative letters. The portrayal of the great humanist, who sees the truth but whose warnings are ignored, was a mirror image of their own situation.