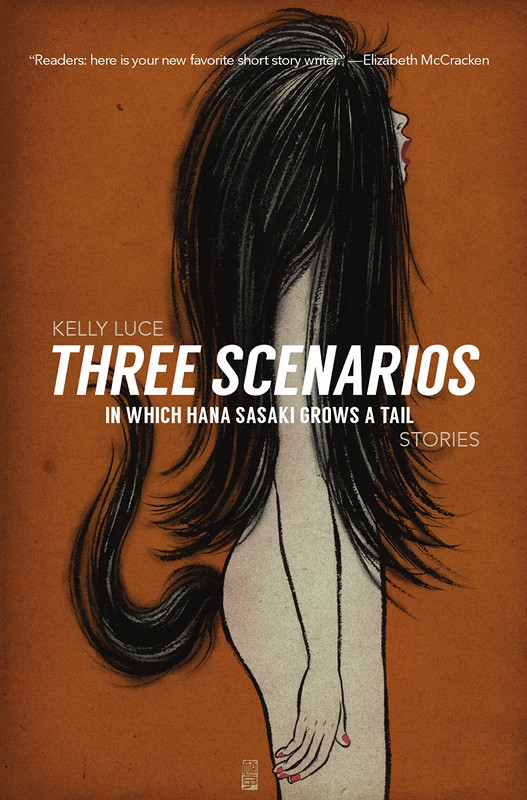

Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail

Read Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail Online

Authors: Kelly Luce

Tags: #Fiction, #Anthology

| Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail | |

| Kelly Luce | |

| A Strange Object (2013) | |

| Tags: | Fiction, Anthology |

HANA SASAKI GROWS A TAIL

The stories in this collection have appeared in slightly different form in the following journals:

“Ms. Yamada’s Toaster” in

Tampa Review

and

Storyville,

“The Blue Demon of Ikumi” in

Salamander,

“Reunion” in the

Kenyon Review,

“Rooey” in the

Literary Review,

“Pioneers” in

Kyoto Journal

(under the title “A Sort of Deadline”), “Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail” in

Shenandoah

, “Wisher” in the

Southern Review

, “Ash” in the

Gettysburg Review

, “Cram Island” in

Kartika Review

, and “Amorometer” in

Crazyhorse

.

“Ms. Yamada’s Toaster” was also featured in the anthology

Tomo: Friendship through Fiction

(Stone Bridge Press, 2012).

Published by

A Strange Object

© 2013 Kelly Luce. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews.

ISBN: 978-0-9892759-0-3

Cover illustration by Yuko Shimizu

Cover design by Eric Amling

Book design by Amber Morena

For my mom

Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail

鰯の頭も信心から

(Iwashi no kashira mo shinjin kara.)

Belief delivers power to even the sardine’s head.

秋茄子は嫁に食わすな

(Akinasu wa yome ni kuwasuna.)

Don’t let your daughter-in-law eat your autumn eggplants.

\

\\\\\\\\\

AT THE TIME, MY UNCLE OWNED

the liquor store and I delivered bottles for him on Mondays, then went back on Fridays and picked up the empties. In this way I got to know the whole town. Pretty much everyone did business with my uncle at one point or another.

Even though I was only fourteen, he let me drive his delivery truck. The hills in town were too steep for a bike; plus, I had to carry around all those bottles.

Old Kumo lived in a shack behind the temple and was brown and furrowed like an old piece of fruit. We kids called him Hoshi-sumomo-san, Mr. Prune, though I never knew whether this referred to his appearance or his diet.

It was from Old Kumo that I first heard about Ms. Yamada’s toaster and how it could predict the way a person’s going to die. I was setting the bottles on his mossy concrete step when he appeared in the doorway and said in a voice as wrinkled as his face, “Son, today I learned how I’m gonna go.”

I had finished with the bottles and stood there, unsure of what to say. I looked up at him because, even though it’s rude to look your elders right in the eye like that, it seemed to be what he wanted.

He told me Ms. Yamada had a toaster that when you put in a piece of bread, it came out with a kanji character toasted on it. That character indicated how you’d die.

“What was your word, sir?”

“Sleep. Isn’t that a hoot? Now I can finally live in peace.” He waved as he shuffled back inside, a bottle of sake clutched in his left hand.

I DIDN’T TELL ANYONE AT HOME

what Old Kumo had said. My parents were too busy—that was the year they opened the udon restaurant—and my sister had just gotten a boyfriend and never hung around after school anymore. Plus, I had a feeling no one would care. Mine was a family of skeptics. We didn’t observe any superstitious holidays, bean-throwing day or Tanabata or anything like that; all we celebrated was New Year’s and that’s because you get to feast for three days straight.

I picked up Old Kumo’s empties on Friday and brought him two extra bottles of sake, which he’d special-ordered

that week. On Monday he was dead. Died in his sleep of natural causes.

Apparently Old Kumo had told a lot of people about Ms. Yamada’s toaster and its prediction for him, though, because once he died, everyone in town was talking about it. Ms. Yamada had always been a little weird. She confirmed everything: the toaster had predicted her husband’s death last year when it popped out a piece of bread that read “heart” three days before he had a coronary, and after that it had foretold her mother-in-law’s fatal pneumonia. A gift from God, she told the crowd gathered around her at the market. She held the toaster under one arm, its plug swinging beneath it like a tail. When asked if she’d gotten a death-predicting piece of toast herself, she said she had.

“Well?”

Hers had read “cancer.” It was quiet for a while after that.

MS. YAMADA WAS JUST LIKE

any other lady you’d see around town except for one thing—she was a real religious nut. Years before the toaster, she’d knocked on our door a couple times, offering her “help.” I remember thinking it was kind of nice—weird, but nice—but after she’d gone my mom would roll her eyes and go back to her TV drama. Anyway, that was back when I was little. By the time the toaster came around, Ms. Yamada didn’t knock in our neighborhood anymore.

Her house was at the edge of town, partway up a huge,

terraced hill with bamboo at the top. For a widow living alone, she had a pretty big standing order at my uncle’s store—eight tall one-liter bottles of beer. That was more than a liter a day! She who smelled so sweet it hurt your nose, like overripe peaches, and spoke very properly and always wore something with lace on the collar—how could

she

go through that much beer?

I thought of her at her impeccable kitchen table, pouring the beer into a glass and waiting patiently for it to settle, then taking the tiniest sip. I pictured her melting at the first drop of bitter liquid in her throat, her creamy makeup running down her neck, pooling between her breasts and in her belly button, and the starch on her collar drooping until her whole body oozed into a peach-scented puddle of foam.

THE TOASTER BECAME A SENSATION.

Some people thought it was a trick she was using to try and convert people, while others believed in the toaster’s power but disagreed about what ought to be done with it. Some wanted to enshrine the toaster and worship it like a Shinto deity. Others thought she should sell it to the government.

But the thing people argued about most was whether or not it was right to use the toaster’s powers, to become One Who Knew. Soon the town divided itself between Knows and Didn’t-Want-To-Knows. Each group, of course, claimed the moral high ground—there was no room for compromise. Conflicting opinions on the topic spoiled countless friendships and were even named in the

Satos’ divorce proceedings as evidence of irreconcilable differences.

Ms. Yamada didn’t get involved in the politics of it. She let anyone use the toaster. She believed it was a gift from God that should not go to waste. Every day there was a line out her door of people, soft pieces of white bread in hand, hoping to find out in what fashion they would meet Death.

But some of the Didn’t-Want-To-Knows were upset. One man, a retired professor from Keio University who everyone just called “Mr. Doc,” went so far as to stand at Ms. Yamada’s open door and protest. He was there talking quietly and intently to a young mother and her toddler on the front steps when I came the next Friday to pick up Ms. Yamada’s empties. They paid no attention to me as I stepped past and set the bottles in the entranceway. I could hear someone crying in the kitchen.

On the way out I passed the mother and child, who were walking toward the road with Mr. Doc. I guess he’d convinced her not to go in. I kept my head down, but as I passed he called to me.

“Keisuke.”

I turned, stunned he knew my name.

“Are you planning to find out?”

I shrugged. It seemed like an awfully big thing to know. Plus I kind of liked thinking that maybe I’d never die, like by the time I got old they’d have invented a cure for everything.

“I’m fighting a losing battle,” he said. “You just can’t protect people from themselves.”

I bowed and walked quickly back to the truck. On the drive down I passed four groups of people climbing the hill to Ms. Yamada’s house. I wondered if Mr. Doc would be able to stop all of them.

BY MONDAY EVERY HOUSE I VISITED

buzzed with talk of the toaster. Ms. Kawabata was predicted to die by fire—the same as Ms. Shinjo. Both were librarians. Extra fire extinguishers were purchased for the older wooden library building, and a state-of-the-art sprinkler system was installed.

A newlywed couple canceled their honeymoon flight to Hawaii because both of their pieces of toast had popped up bearing the character “air.”

At dinnertime my parents and sister talked about how nuts everyone was, but I kept quiet. I didn’t necessarily believe in the toaster, but I was at least willing to be convinced, maybe.

The news reached all over the prefecture. The line spilled out Ms. Yamada’s door and down the steps. News vans crowded the narrow street so that I had to drive fifty meters away to park.

Mr. Doc held forth on the front stoop. “Don’t let curiosity pollute your mind!” he bellowed at the line, which was full of unfamiliar faces. A few college-age kids stood with him, holding signs and chanting, “Knowledge of death sullies the will to live!” The crowd ignored them and was silent, as if in line to receive a blessing. I stepped through the mob with the beer, excusing myself and sneaking

peeks at the faces. Some people seemed lost in thought, staring up at the bamboo grove beyond the house, while others whispered nervously to one another.

“Hey, no cuts, buddy,” someone said as I passed. I held up the crate of beer and almost said, “Delivery,” but then I thought that maybe Ms. Yamada didn’t want these people to know she’d ordered all this beer, so I turned back.