Three Weeks With My Brother (16 page)

Read Three Weeks With My Brother Online

Authors: Nicholas Sparks,Micah Sparks

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography

“Hey guys! It’s great to see you! I can’t tell you how much I missed you today!”

Then, she’d visit with each of us, asking about our days. And one by one, Micah, Dana, and I would fill her in as she began cooking dinner.

She was also a giggler. My mom could laugh at anything, which naturally drew people to her. She wasn’t Pollyanna, but she seemed to realize that life had both ups and downs, and it wasn’t worth the energy to get upset about the downs, since not only were they inevitable, but they’d pass as well.

My mom also seemed to know

everyone’s

parents, and when I’d meet someone new, this new friend would frequently mention how much

their

mom liked visiting with

my

mom. This always struck me as a mystery, because my mom had no social life. Almost all her evenings and weekends were spent at home with us, and she ate lunch alone. Nor, by the way, did my parents socialize together, or even go out on what might be considered a date. In all my years growing up, I remember my parents going out to a party together only

once,

and it was downright shocking to us when they casually mentioned that they were going out for the evening. I was thirteen at the time, and after they left, Micah, Dana, and I called a powwow to discuss the extraordinary turn of events. “They’re leaving us on our own? What can they be thinking? We’re just kids!” (Never mind that we were on our own

every

day . . . but who needs logic when you’re feeling sorry for yourself?)

How, then, did people know her? It turned out that various parents of new friends were attended to by my mom at the optometrist’s office, and struck up conversations with her. But it wasn’t simply idle talk; my mom had a way of getting people to open up to her. People told her everything—she was the veritable Ann Landers of Fair Oaks, and occasionally, when I mentioned a new friend, she’d shake her head, and say something like, “It’s fine if he comes here, but you can’t go over there. I know what goes on in that house.”

Yet, my mother was—and always will be—an enigma to me. While I knew she loved me, I couldn’t help but wonder why she wouldn’t acknowledge my successes. While we kids were the center of her life, she let us run wild in dangerous places, doing dangerous things. These inconsistencies have always puzzled me, and even now, I’m at a loss to explain them. I’ve long since given up trying to understand it, but if there was anything consistent in the way she raised us, it was in her refusal to allow any of us to indulge in self-pity of any kind. She achieved this through a maddening style of argument, in which the following three statements were repeated in various sequences:

A. It’s your life + social commentary.

B. What you want and what you get are usually two entirely different things.

C. No one ever said that life was fair.

For example, an argument I had with her when I was eleven:

“I want to go out for the football team,” I said. “There’s a Pop Warner league, and all my friends are playing.”

“It’s your life,” she answered. “But I don’t want to be responsible for you hobbling around on crutches your whole life because you blew out your knee as a kid. And besides, we don’t have the money for it.”

“But I want to.”

“What you want and what you get are usually two entirely different things.”

“That’s not fair. You always say that.”

She shrugged. “No one ever said that life was fair.”

I paused, trying another approach.

“I won’t get hurt, if that’s what you’re worried about.”

She looked me over. “Someone your size? You’d definitely get hurt. I’ve seen football players. You’d be nothing more than a bug on the windshield to them. You’re too small.”

She had a point there. I was small.

“I wish I was bigger. Like my friends are.”

She put a consoling hand on my shoulder. “Oh sweetie, no one ever said life was fair.”

“I know. But still . . .”

“Just remember this, okay?” she’d offer, her voice softening with maternal affection. “It’ll help you later in life when you’re disappointed about anything. What you want and what you get are usually two entirely different things.”

“Maybe you’re right. Maybe I should try another sport.”

My mom would smile tenderly, as if finally conceding the argument. “Hey, do what you want. It’s your life.”

The older I got, the more I hated these arguments, because I lost every one of them. But still, deep down, I could never escape the feeling that my mom was probably right about most things. After all, she spoke from experience.

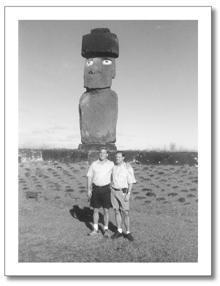

Easter Island, Chile

January 29–30

A

s we looked out the airplane window, Easter Island slowly came into view, a remote and exotic sight that only underscored how far from familiar surroundings we were.

Easter Island, like most islands in the South Pacific, was first settled by Polynesians. But because Easter Island was so far from the rest of populated Polynesia—nearly 2,200 miles from the coast of Chile, it’s the remotest inhabited island in the world—the native people developed their own unique culture, which included the carving of giant statues known as the Moai.

Of all the places listed in the original brochure, Easter Island had been the most intriguing to me. I’d read about the Moai and had longed to see and touch them ever since I was a child. Because it was so remote, I fully realized that this trip might be the only time I ever set foot on the island, and I craned my neck, looking out the window as we circled in preparation for landing.

What struck me immediately was the scarcity of trees. I suppose I’d imagined the palms and rain forests typical throughout the South Pacific, but instead the island was largely covered with grassy meadows, as if part of Kansas had been dropped into the middle of the ocean. Later, we’d find out from the archaeologists that the absence of trees partially explains the cultural history of Easter Island, but at the time I remember thinking how odd it seemed.

Another interesting thing about Easter Island is the time zone in which it is located. Because we were flying west, we would cross time zones and lose a day on our way to Australia, but it enabled us to maximize our days. If we left at ten, for instance, and flew for five hours, we might arrive only three hours after we departed, as measured by local time. But because the island is part of Chile and thus shares the Eastern Time Zone (along with New York and Miami, despite lying geographically west of California), we were told that the sun wouldn’t set until 10:45

P.M.

Dinner was served outdoors, and afterward, a few of the tour members strolled over to a seaside bluff to watch the sun go down. Waves crashed violently against the rocks, the plumes rising forty to fifty feet in the air. In the west, the sky turned pink and orange, before finally changing into the brightest red I’ve ever seen. And then an impenetrable darkness descended.

Micah and I were sitting together, watching all of this when he finally turned to me.

“I think I know what your problem is,” he said.

“What problem?”

“Why you get so stressed all the time.”

“Why do you keep talking to me about this? Here I am, enjoying my first South Pacific sunset, and you want to start probing my psyche.”

“Your problem,” he said, ignoring me, “is that you need more friends.”

“I have friends. I have a lot of friends.”

“Guy friends?”

“Yeah.”

“But do you do anything with them? Do you go out with them? Go fishing or boating or whatever it is you do down south?”

“Sometimes.”

“Sometimes, or rarely?”

I hesitated. “Okay, so I don’t do much with them. But I can’t. To have the time to go out with friends, I’d have to give up time with my family. I have too many kids to do that. And besides, most of my friends have kids, too. I’m not the only one who doesn’t have a lot of free time to just hang out.”

“You should, though. Just hang out. Not all the time, of course, but you should try to make it more regular. Like I do. I joined an indoor soccer league and we play every Thursday. Just a group of guys out there having fun. You should do something like that.”

“We don’t have an indoor soccer league. I live in a small town, remember?”

“It doesn’t have to be soccer. You can do anything. The point is that you should do something. Relationships are the most important thing in life, and friends are part of that.”

I smiled. “Why do I get the impression that you think the solution to all my problems is to be more like you?”

“Hey, if the shoe fits.” He shrugged, and I laughed.

“So you still think you have to take care of me, huh?”

“Only when I think you need it, little brother.”

“And what if I started talking to you about God, because I think you need it?”

“Go ahead,” he said. “I’ll listen.”

Above me, the sky was filled with stars clustered together in unrecognizable constellations, and the words rose up almost unexpectedly.

“God keeps his promise, and he will not allow you to be tested beyond your power to remain firm; at the same time you are put to the test, he will give you the strength to endure it, and so provide you with a way out.”

Micah glanced over at me. Despite the darkness, I could see him raise his eyebrows.

“First Corinthians,” I said. “Chapter 10.”

“Impressive.”

I shrugged. “I just always liked that verse. It reminds me of the footprints story—you know the one where God walks with man on the beach. Scenes from the man’s life flash in the sky, and during flashbacks of the most trying times of the man’s life, he sees only one set of footprints. Not because God abandoned the man in times of need . . . but because God carried the man.”

Micah was quiet for a moment. “So you don’t think he abandoned us?”

“No,” I said. “And I don’t think he wants you to abandon him either.”

The following morning, we set off to see the first of the Moai statues, which were located less than a few minutes from the hotel, just up the coast. Had we known where we’d be going, we could have seen them from our hotel room.

As we rode in the vans with the archaeologists who made their living studying them, we were informed that at one time there were roughly fourteen different tribes on the island, each with its own ruler. These rulers ordered the carving of these statues from volcanic rock—most were made to resemble said rulers—and over time, these statues grew larger and larger, as each ruler tried to impress on the people his own importance. Some of the Moai weigh up to thirty tons, and stand twelve feet high; one unfinished statue mea-sures sixty-six feet and is estimated to weigh nearly fifty tons.

Afterward, we were told about the absence of trees.

When it was first colonized, Easter Island had resembled other islands in the Pacific, but as the population expanded, trees became the most overused of all the natural resources. They were employed in construction of dwellings and for cooking fires; mature trees were used to roll the Moai across the island. In the past when Polynesians migrated, as islands became overcrowded, people would head off in their canoes in search of new territories; because Easter Island was so isolated, there was nowhere else to go. Overcrowding and overuse of the resources led to civil wars; the wars continued through generations. Through it all, trees continued to be cut down. In the end, most had been wiped out, and the natives ended up burning anything they could in order to cook, including their homes and canoes. Shore fishing became the sole source of food, but a La Niña effect is suspected to have suddenly cooled the waters around the island. It lasted two years, killing much of the ocean reef, and the fish became much less plentiful. In the end, the natives turned to cannibalism.

Over time, a few palms eventually sprouted again, but to speed the process, mature palm trees were imported from Tahiti. These trees, however, turned out to be diseased, and they not only died, but ended up killing most of the remaining palms on the island. Now, there are only a few spots where they still remain.

The first statue we saw was fascinating. So were the second and third. By the time we viewed the fourth and fifth statues, the novelty began to wear off. Though the local archaeologists assured us that each was different, to my untrained eye they all looked pretty much the same: eye sockets, long ears, nose, and mouth, all carved from lava rock.

From there, we headed to the volcano quarry, where they’d been carved. To reach it, you had to cross the island, and the distance these statues had been transported fascinated me more than the statues themselves. As we drove, I tried to imagine how many people it had taken to move a single statue, let alone hundreds.