Tiger Men (76 page)

‘Now Hugh,’ he said reasonably, ‘I understand your reluctance to capitalise on your VC for business purposes . . .’ No, he didn’t. ‘. . . but you can’t go to the other extreme and hide away from the fact that you’re a war hero – that’s foolish. You have a debt to the public, my boy, can’t you see that? They want their champion, Hugh. They’re proud of you, just as I am. You mustn’t deprive the people of their home-grown hero.’

Hugh had had enough by now. He stood, signalling a halt to the meeting. ‘I have made up my mind, Father. I will do no further interviews. I wish to put the war behind me.’

Reginald was angered that his son should behave in so peremptory a fashion and he rose to his feet. ‘For God’s sake, boy, what’s wrong with you?’ he snapped. ‘You could at least offer the press one simple interview. It’d take you all of ten minutes. Is that too much to ask? A photograph of you and your VC on the front page of

The Mercury

and everyone’d be happy.’

‘I couldn’t do that, I’m afraid.’

‘Why the devil not?!’

‘I don’t have the VC any more.’

‘What do you mean you don’t have it?’

‘I gave it away.’

‘You gave away your VC.’ Reginald didn’t believe him for a minute. ‘You gave it away, just like that,’ he said with a click of his fingers, ‘a Victoria Cross.’

‘Yes I did.’

He’s serious, Reginald thought. The boy was looking him straight in the eyes and he was deadly serious.

‘What’s going on, Hugh? What are you talking about? You gave it to whom? The army? Why would you give your VC back? I don’t understand.’

‘I gave it to Thomas Powell.’

‘Thomas Powell,’ Reginald repeated parrot-like. He recalled Thomas Powell, the lout from Charlotte Grove Estate who’d threatened to beat him up all those years before. ‘Why would you give your Victoria Cross to Thomas Powell?’

‘Because it rightfully belongs to his son David.’

‘What in God’s name are you talking about?’ Reginald was becoming flustered. It was all too ridiculous; this couldn’t be happening. ‘The medal belongs to you. The deeds of valour that earned the VC were yours. You performed those actions.’

‘I don’t remember performing them.’

‘That’s beside the point,’ Reginald yelled in his frustration. ‘Battle fatigue is common! Men have been known to lose their memory! Your acts were witnessed, for God’s sake! I’ve read the citation! You performed those deeds!’

‘I could not have performed them if I’d been dead though, could I, Father?’ Hugh calmly replied. ‘David Powell saved my life by forfeiting his own. The VC has gone to its rightful owner.’

It was his son’s composure that pushed Reginald over the edge. How could Hugh stand there so coolly and throw this insult in his face? Suddenly, and without warning, Reginald was consumed by the blackest rage.

‘You’ve done this to spite me, haven’t you, boy? You’ve done this to get back at me for Rupert.’

‘No Father, I have not –’

But Reginald was too far gone. His pent-up anger was unleashed, and there was no holding him back. ‘It’s all been to spite me! The O’Callaghan girl, the VC, everything! You dare to marry an Irish Catholic whore! You drag our family name through the mud! And now you give away the Victoria Cross! Dear God, how much more am I expected to take?!’ He stormed out from behind his desk, his right hand raised, his finger pointing accusingly. ‘You’re my only son, damn you! I’ve worked my whole life on your account. I’ve built an empire for you to inherit, and this is the thanks I get. I give you the world and this is how I’m rewarded!’

The finger was now jabbing the air barely inches from Hugh’s face, but Hugh made no move.

‘Ingrate!’ Reginald screamed. ‘Ingrate!’

Hugh wondered whether perhaps he should fetch help. His father’s eyes were the eyes of a madman – was he having some sort of fit? Then even as he watched he saw the eyes become confused and lose focus and he saw the trickle of blood coming from his father’s nose.

Reginald knew something was wrong. He felt a tingling in his right hand, but when he lowered it and made to grasp it with his other hand he discovered his left arm would not respond. He opened his mouth to scream further invective at his ingrate of a son, but the words that came out were no more than a drunken slur, and for some strange reason he seemed to be losing his balance.

Hugh caught his father as he fell.

The massive stroke Reginald Stanford had suffered had not killed him. It had, however, left him totally incapacitated, with no expectation of recovery. Following his treatment at the hospital, the doctor recommended he be transferred to a hospice where he could receive the constant attention a case like his required until the event of his death, but Hugh would not have it. Hugh insisted his father be brought home to Stanford House. He would employ a full-time male carer and a live-in nurse, he told the doctor.

‘Who knows, perhaps there is a vestige of consciousness remaining. Perhaps he may recognise he is in his own home, which would be of some comfort,’ Hugh said, looking down at the motionless form of his father.

‘I very much doubt that would be the case,’ the doctor replied. ‘He’s showing no such signs, and the stroke was extremely severe. Indeed, it’s amazing he survived at all. But he appears to have a very strong cardiovascular system. In fact I must warn you, Mr Stanford, providing your father does not suffer another stroke, he might well live on for years in this semi-vegetative state. At fifty-nine he’s still a comparatively young man and, according to his medical history, longevity runs in your family.’

‘Yes, indeed it does. My grandfather lived well into his nineties.’

‘Well, there you are then, certainly something to bear in mind if you’re contemplating home care.’

Reginald heard every single word they uttered.

Reginald Stanford’s mind was intact. He knew precisely what was going on. He also knew what he looked like. He saw himself in the mirror every humiliating time they carried him into the bathroom and placed him on the toilet, and then afterwards when they lifted him off and washed his backside. He was abhorrent, his body gnarled, his arms bent, his hands claw-like. His eyes stared vacantly at nothing, his mouth hung open slackly and when they fed him food dribbled down his chin. He drooled even when he wasn’t being fed. He was far more grotesque than his father had ever been.

They took him back to Stanford House several days later.

The male carer, a giant of a man called Simon, made a daily habit of carrying him downstairs and seating him by the bay windows of the larger drawing room where the sun flooded in.

It was here that Hugh, having been granted power of attorney, conducted his initial meeting with the chief executives of Stanford Colonial. Hugh considered it only right that the meeting should be conducted in the presence of his father.

Reginald listened as they talked about him, Nigel Lyttleton and his son Walter and the others, saying what a terrible thing his stroke was, glancing occasionally in his direction then quickly averting their eyes. They talked about other things too, and he learnt it was rumoured that Henry Jones was to be knighted for his services to the British war effort.

Henry Jones was to be knighted? Reginald’s mind screamed at the idea.

Sir Henry Jones? That vulgar little man? What about me? I donated an aeroplane too!

And he heard them say also that Henry intended to build a fleet of ships.

‘They’re already referring to it as “the jam fleet”,’ Nigel said, and the others laughed.

Henry Jones was to have his own fleet of ships?

But that was my dream,

the voice in Reginald’s brain screamed,

my dream

,

mine!

As they left, they once again looked in his direction pretending sympathy. ‘Poor old Reginald,’ Nigel said, but it was clear they found the sight of him repulsive.

The only one who was not repelled by his appearance was Rupert. Rupert often sat beside him, wiping away the drool with the bib that the nurse had placed around his neck.

‘Poor Father,’ he would say, stroking Reginald’s withered hand, ‘poor, poor Father.’

PILOGUE

P

ONTVILLE,

1926

‘T

here you go, Evy, tiger food.’ Caitie handed her daughter the parcel of meat scraps. ‘There’re some nice juicy bits in there – she’ll like that.’

‘Thank you.’ Six-year-old Evelyn took the parcel from her mother then turned and raced full bore out of the kitchen, only to collide with her father, who’d just come in the back door.

‘Hello, Evy.’ Hugh picked his daughter up in his arms and kissed her. ‘Where are you off to in such a hurry?’

‘To feed my tiger,’ the little girl said, waving the parcel under his nose.

‘Yes, of course you are, silly me.’ Hugh exchanged a smile with Caitie as he set the child down. ‘Off you go then.’ Evy, coppery curls bouncing, headed purposefully out the back door.

They’d been humouring her for over a month now, ever since the announcement that had followed their visit to the museum where Evie had seen a stuffed thylacine. Her mother had explained that the animal was known as a Tasmanian tiger. ‘They’re very, very rare,’ Caitie had said. ‘No-one sees tigers any more.’

The announcement had come less than one week later.

‘I have made friends with a tiger,’ Evy had said. It had been a very solemn announcement, which her parents knew must be taken seriously.

‘Really,’ Caitie said, ‘a tiger – goodness me.’

‘Yes. She lives in a little cave among the rocks up on the hill, and she has babies. I talk to her and she understands me. She’s my friend.’

‘A tiger for a friend,’ Hugh said, impressed. ‘You’re a very lucky girl.’

‘Yes, I am.’ Evy nodded. ‘That’s why we have to keep her a secret. You mustn’t tell anyone about her, particularly Uncle Rupert, because he gets too excited. Uncle Rupert would scare her and she would run away.’

‘We won’t tell Uncle Rupert,’ Hugh promised. ‘We’ll keep it our secret.’

Evy reflected for a moment. ‘You can tell Uncle Harry, though.’

‘Really,’ Caitie asked. ‘Do you think that’s wise?’

‘Yes, I do. Uncle Harry will protect her.’ Evy trusted her Uncle Harry implicitly. ‘If Uncle Harry knows my tiger is there, then he’ll keep people from going near her cave. She’s very frightened; she told me so. I’m her only friend. And even I don’t go too close. She’s warned me not to, or she’ll run away.’

‘Very well,’ Caitie said. ‘I promise we’ll tell no-one except Uncle Harry about your tiger. It will be our very special secret. And we’ll keep away from the rocks up on the hill.’

Evy had nodded, she’d been happy with that.

Following his Aunt Amy’s death at the ripe age of eighty-six, Hugh had moved his wife and newborn daughter, together with his brother, Rupert, out of the city and into the old farmhouse at Pontville, driving into town every second week for several days of business meetings on behalf of Stanford Colonial. His cousin Harry, who worked the property and chose to live alone in the nearby foreman’s cottage, had quickly become a part of the family, he and Evy developing a special relationship over the years.

Hugh and Caitie had presumed the tiger fantasy that had been born of Evy’s visit to the zoo would soon fade, but it didn’t. As time passed, Evy’s newfound friend began to play a more and more dominant part in her life.

‘I told my tiger I would bring her some food,’ she said one day. ‘I told her I would leave it outside her cave, and it was a promise, Mummy, so I can’t let her down. She said she would like that very much and she was very grateful, but I forgot to ask her what she eats.’

‘I’ll get you some meat scraps, darling,’ Caitie had said, and that had been the start of the tiger-feeding ritual.

Evy would visit the cave in the late afternoon. She would sit and chat for a while before leaving the meat.

‘My tiger loves her dinner,’ she told her parents. ‘She eats it at night. I know, because it’s always gone the next morning.’

‘There are lots of animals who might eat the meat during the night, Evy,’ Hugh said with care. He was starting to wonder whether things were perhaps getting a little out of hand.

‘No, no,’ Evy protested, ‘my tiger eats her dinner. She tells me so, and she thanks me for bringing it. She’s very polite.’

Hugh voiced his concern to Caitie. ‘Do you think we’re wrong to indulge her like this? It’s not altogether normal, surely.’

‘Of course it is, darling. Lots of children invent imaginary friends. Evy’s been an only child for quite some time now; she’s probably been lonely. She’ll forget all about her tiger when David’s bigger and they can play together.’

After five years, Hugh and Caitie’s long-awaited second child had finally arrived. Baby David was just eight months old.

Hugh stopped worrying. ‘Of course,’ he said. ‘You’re right.’ Caitie knew best. Caitie was a born mother.

The animal senses no threat from the child who visits her daily. But where there is a child there are men, and at dusk when she hunts she can see the house in the valley below. She is forever wary. As soon as her cubs are old enough she will leave this place.

She watches from her small rocky lair as the child places the meat on the ground and sits some distance away. The child talks and the sound of her voice signals no danger, for the animal has become accustomed to it.

The child leaves, and the animal waits, her sharp, black eyes trained on the meat. The meat will provide a tasty morsel for her cubs before she sets off on her hunt. But she will not leave her lair until dusk settles in.

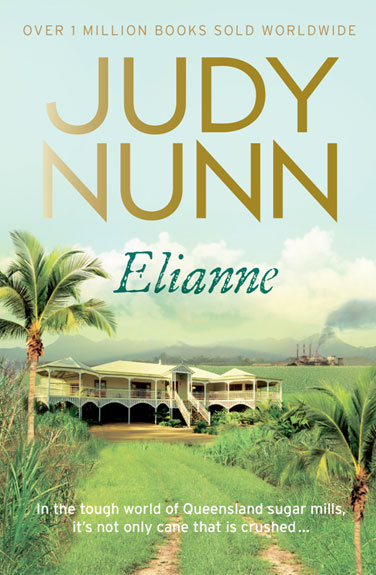

Elianne

Available November 2013