Titanic (10 page)

Authors: Deborah Hopkinson

Murdoch tried his best. He had so little time.

The seconds ticked by. Thirty-seven seconds in all.

They were not enough.

(Preceding image)

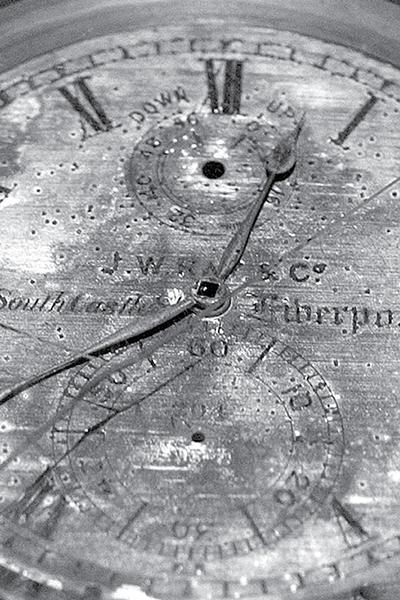

A chronometer from the bridge of the

Titanic

, which was raised from the wreck of the ship.

“It was not a loud crash; it was felt almost as much as heard. . . . I sat up in bed and looked out of the nearest port. I saw an iceberg only a few feet away, apparently racing aft at high speed and crumbling as it went. I knew right away what that meant.”

— Henry Harper, first class passenger

11:40 p.m. Collision!

Quartermaster Alfred Olliver was walking onto the bridge when he heard a “long, grinding sound.”

In the crow’s nest, the iceberg seemed like “a great, big mass” to lookout Frederick Fleet. Beside him, Reginald Lee watched it approach through the haze, all dark with only a “white fringe” along the top. As the iceberg passed he saw that the back of it appeared white.

Captain Smith was on the bridge in a flash. He got Murdoch’s report and together they used the regular and emergency telegraph to send an ALL STOP signal to the engine room.

At the moment of impact, fireman George Beauchamp, down below in Boiler Room 6, was startled by a noise like thunder. He’d just heard stoker Fred Barrett shout, “Shut the dampers!” Closing the dampers on the furnaces was part of the process of stopping the engines.

Cold ocean water began leaking in from gashes in the hull about two feet above the deck. Seconds later, Fred Barrett and second engineer James Hesketh raced out of Boiler Room 6, back toward Boiler Room 5. The watertight door between the two boiler rooms, which Murdoch had closed from the bridge, slammed down shut behind them. George Beauchamp continued to work — for perhaps as long as twenty minutes — before he and other firemen scrambled up an escape ladder to get out of the steam-filled room, with water still pouring in.

At 11:41 p.m. the

Titanic

’s engines stopped for the first time.

Captain Smith and Murdoch walked back along the starboard side of the bridge to try to catch a glimpse of the iceberg as it receded in the distance. Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall tagged along, but he couldn’t spot the berg.

Captain Smith sent Boxhall off to do a quick inspection. Boxhall hurried down to the third class passenger accommodations forward on F Deck, looking for damage.

Awakened by the collision, White Star Line managing director J. Bruce Ismay didn’t stop to dress. Throwing a coat over his pajamas, he made his way to the bridge right away to talk to Captain Smith. The two stood together for several minutes, but no one heard what they said.

Then, at 11:47 p.m., Captain Smith ordered the engines to start up “half ahead.”

It’s not certain what he had in mind. He didn’t have damage reports in yet. So why start moving again? Some people think he and Ismay may have discussed heading for Halifax, Nova Scotia, which was closer than New York. Maybe the two men hoped the ship could somehow limp into harbor safely. But that was not to be.

Meanwhile, Boxhall returned with good news. He’d seen “no damage whatever . . .” Captain Smith must have been relieved — at least for a few minutes. But it was a large ship and he needed more information. Boxhall testified later that the captain sent him off again, this time to find the carpenter to check, or “sound,” the ship.

In the Marconi room, Harold Bride, the

Titanic

’s junior wireless operator, had just woken up. He wasn’t aware of the commotion or even the collision itself. “I didn’t even feel the shock . . .” Bride said. “There was no jolt whatever.”

Bride was trying to convince senior operator Jack Phillips to get some rest when Captain Smith stuck his head into the wireless cabin. Bride remembered it this way:

“‘We’ve struck an iceberg,’ the Captain said, ‘and I’m having an inspection made to tell what it has done for us. You better get ready to send out a call for assistance. But don’t send it until I tell you.’”

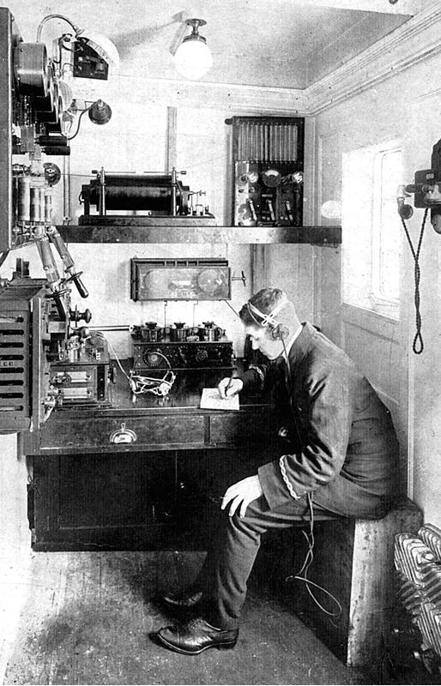

(Preceding image)

Marconi wireless operators on board ships of the time worked long hours transmitting messages from passengers to friends and family onshore.

Captain Smith soon found out that Boxhall’s report was too good to be true. Boxhall had gone only to F Deck: But the damage was in the lowest level of the ship, where the cargo holds and boiler rooms were located.

Sent to find the carpenter, Boxhall ran into him at A Deck, “absolutely out of breath.” Carpenter John Hutchinson was already hurrying to the bridge to report bad news: The ship was making water fast. Boxhall also met a mail clerk hurrying to the bridge to tell the captain that the mail hold was filling with seawater.

Six minutes earlier, Captain Smith had ordered the engines half ahead.

Now, at 11:53 p.m., he couldn’t ignore the serious reports he was getting. He gave the command for ALL STOP.

Then it was time to investigate for himself.

While Captain Smith was trying frantically to find out just how badly the ship was damaged, many on board were barely aware that anything was wrong.

When the ship struck the iceberg, Lawrence Beesley was in his cabin, curled up with a book. At first the only thing he was aware of was “an extra heave” of the engines. “Nothing more than that — no sound of a crash or of anything else,” he said, “no sense of shock, no jar that felt like one heavy body meeting another. . . .”

Lawrence went back to reading. Then the engines stopped.

Now that made him curious. He wondered if the ship had dropped a propeller. Since this was his first time at sea, Lawrence was interested in everything that went on. Why not go exploring? He threw a dressing gown over his pajamas and pulled on his shoes.

In the corridor he spotted a steward and asked why the ship had stopped. The answer the steward gave him was similar to what many passengers first heard: “‘I don’t suppose it is anything much.’”

Lawrence wasn’t worried either at this point. How could anything really be wrong with the massive, magnificent ship on such a clear, still night? In fact, he began to feel a bit foolish roaming around the ship in his dressing gown. He didn’t see anyone else at first, and it

was

awfully cold.

Still, curiosity got the better of him and he kept on with his wanderings, making his way up to the Boat Deck. Outside, the bitter cold cut him like a knife.

Once again, nothing seemed to be wrong. It was cold and clear — no iceberg or other ship in sight. Beesley went down to the first class smoke room on A Deck, where some fellow passengers had an answer for him: Yes, they’d seen an iceberg go by. But, no, they certainly weren’t taking

that

very seriously.

“‘I expect the iceberg has scratched off some of her new paint,’ said one, ‘and the captain doesn’t like to go on until she is painted up again.’”

The joking continued. Another man held out his glass of whiskey and laughed, “‘Just run along the deck and see if any ice has come aboard: I would like some for this.’”

Then Lawrence noticed that the ship had started again, “moving very slowly through the water with a little white line of foam on either side. I think we were all glad to see this: it seemed better than standing still.”

Reassured that they were once again on their way, the young teacher turned to go back to his cabin, book, and warm bed. After all, it must be some minor problem; nothing to worry about. But as he headed down the stairs to his cabin he saw something that made him stop in his tracks: The ship seemed just slightly tilted lower toward the bow, or front end.

He began walking down the steps, a little more worried now. It was hard to describe, but something was definitely wrong. He had “a curious sense of something out of balance and not being able to put one’s feet down in the right place.”

Lawrence went back to his cabin and his book. It wouldn’t be for long.

On the bridge, Captain Smith stopped at the Marconi room on his way to inspect the ship to order the wireless operators to send the international call for assistance: CQD.