Titanic (16 page)

Authors: Deborah Hopkinson

First class passenger Emily Ryerson and her three children were also waiting to get into Lifeboat 4 from A Deck.

“There was a rough sort of steps constructed to get up to the window,” she remembered. “My boy, Jack, was with me. An officer at the window said, ‘That boy can’t go.’”

Emily Ryerson must have felt her heart pound in disbelief. Her husband stepped forward and said in a firm voice, “‘Of course, that boy goes with his mother; he is only 13.’”

“So they let him pass,” remembered Emily. “They also said, ‘No more boys.’ I turned and kissed my husband, and as we left he and the other men I knew — Mr. Thayer, Mr. Widener, and others — were all standing there together very quietly.”

The water had kept on rising. After Emily Ryerson got into a lifeboat, she looked back up at the

Titanic

. It seemed to her that the Boat Deck was probably no more than twenty feet above the water.

As more boats left, Archibald Gracie and his friend James Clinch Smith began to call out frantically, looking for more women. “‘Are there any more women? Are there any more women?’”

Colonel Gracie could now feel that the

Titanic

was listing heavily to port. The deck was on a slant, and it felt, thought Archibald Gracie, as if the ship was about to topple over.

And then all the regular lifeboats on the port side were gone.

“‘All passengers to the starboard side,’” Gracie heard Lightoller command.

It seemed to Colonel Gracie that “the final crisis had come.”

For a long time, third class passenger Ole Abelseth and his companions had waited for instructions on the Poop Deck. Finally someone came and called for women to go up. Ole explained, “We stayed a little while longer, and then they said, ‘Everybody.’ I do not know who that was, but I think it was some of the officers that said it. . . .”

But to their surprise, most of the lifeboats were gone.

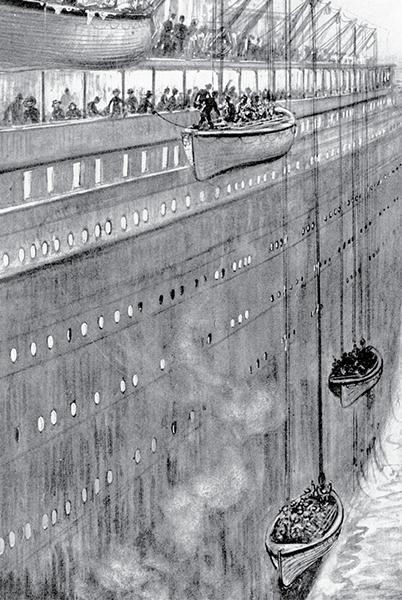

“We went up. We went over to the port side of the ship, and there were just one or two boats on the port side . . . We were standing there looking at them lowering this boat,” said Ole.

“We could see them, some of the crew helping take the ladies in their arms and throwing them into the lifeboats. We saw them lower this boat, and there were no more boats on the port side. So we walked over to the starboard side of the ship, and just as we were standing there, one of the officers came up and he said just as he walked by, ‘Are there any sailors here?’”

Ole was torn: Unlike his friends and relatives, he understood English. He had experience at sea. He could easily have spoken up. And it might be his only chance to live. What should he do? In the end, loyalty to his companions won out.

“I did not say anything . . .” Ole reflected. “I would have gone, but my brother-in-law and my cousin said, in the Norwegian language, as we were speaking Norwegian: ‘Let us stay here together.’”

And so Ole and his relatives stayed in place. And as he stood in the confusion on deck, he happened to over–hear an extraordinary conversation between two of his fellow passengers.

“Just a little ways from us I saw there was an old couple standing there on the deck, and I heard this man say to the lady, ‘Go into the lifeboat and get saved.’

“He put his hand on her shoulder and I think he said: ‘Please get into the lifeboat and get saved.’

“She replied: ‘No; let me stay with you.’

“I could not say who it was,” said Ole later, “but I saw that he was an old man.”

Ole Abelseth’s experience was typical of many third class passengers. Some made their way to the Boat Deck on their own. Others got as far as the main staircase on D Deck, where they were told to wait for further instructions. Some groups of women and children were escorted to the boats, but the men were kept back. Third class passengers did not know their way around the ship, and there was no clear path from the third class area to the Boat Deck. There were also gates separating the areas.

Twenty-one-year-old Daniel Buckley, on his way to New York from Ireland to try to make some money, described one man’s efforts to get through a little gate at the top of the stairs leading to the first class deck. “There was one steerage passenger there, and he was getting up the steps, and just as he was going in a little gate a fellow came along and chucked him down; threw him down into the steerage place . . .”

The seaman had also apparently locked the gate, though it hadn’t been locked before. Angered, the passenger who’d been thrown down broke the lock and went after the sailor. “He said if he could get hold of him he would throw him into the ocean.”

Meanwhile, the lifeboats were being lowered — some not filled to capacity. Why not? At first many women didn’t want to get in. Some crew members seemed to think that the boats would also be filled from decks below; others assumed that the lifeboats would stay nearby and wait for further instructions, or return for more people.

And, as researcher David G. Brown points out, people were simply not called to the boats in any clear way. The first women and children who went out into the cold night air were helped into boats immediately. But many more stayed inside, in public rooms, waiting for instructions.

There was no organized plan to fill the boats or make sure third class passengers could find their way to the lifeboats. In fact, there were no organized plans at all.

Thirty-one-year-old steward John Hart was assigned to almost sixty third class passengers, mostly women and children, down on E Deck. Right after the collision he’d helped passengers into their bulky cork life belts, though some, he said, seemed reluctant to wear them and just wanted to stay in their cabins.

Many passengers did not really understand the danger. After all, Hart himself had begun by reassuring them that nothing was seriously wrong. The reason, he said, was “to keep them quiet.” Language was also a barrier for a number of immigrant families.

For a while, everyone just waited for instructions. At about 12:30 a.m., the word had come down to Hart and other stewards to bring women and children up to the Boat Deck. It took Hart some time to organize a group. Hart testified that he escorted about thirty women and children to Lifeboat 8, but researchers question this as no third class passengers were rescued in this boat.

It would have been hard for these passengers to find the way on their own into parts of the ship where they had never been. As Walter Lord notes in

A Night to Remember

: “It was a long trip — up the broad stairs to the Third Class lounge on C deck . . . across the open well deck . . . by the Second Class library and into First Class quarters. Then down the long corridor by the surgeon’s office, the private saloon for the maids and valets of first class passengers, finally up the grand stairway to the Boat Deck.” No wonder third class passengers needed a guide.

After escorting his first group to the boats, John Hart returned and organized about twenty-five people. He noticed two other stewards also leading groups of third class passengers to the boats.

But once again, the trip took time — time to gather a group of women and children together, time to separate them from men (Hart’s orders were to not bring men), and time to get everyone moving along.

By the time Hart got to the Boat Deck with his second group of women and children, he could see only one regular lifeboat available on the starboard side.

“I took them to the only boat that was left then, boat No. 15,” Hart told investigators.

As he helped the passengers in, First Officer Murdoch stared at him and asked, “‘What are you?’

“I said, ‘One of the crew. I have just brought these people up.’

“He said, ‘Go ahead; get into the boat with them.’”

At 1:40 a.m., John Hart climbed into Lifeboat 15 (the boat that almost landed on top of Lawrence Beesley and others on its way down). Even if he had tried, he wouldn’t have had time for another trip.

Although stewards like John Hart did their best, more third class passengers perished than in any other class. They were located farther away from the lifeboats. They were accustomed — by regulations and practice — to stay in their own areas and wait for instructions. Also, unlike first and second class passengers, men in third class were not allowed to escort their wives to the boats, encourage them to get in, or see them safely off. For passengers who did not speak English, trying to understand what was happening was even harder.

Someone had opened the gate leading to the first class deck area for third class women at around 1:30 a.m. By 2 a.m., men were allowed up too. Third class passengers began to surge onto the upper decks.

But by two in the morning on the

Titanic

, it was already too late.