To Sell Is Human: The Surprising Truth About Moving Others (25 page)

Read To Sell Is Human: The Surprising Truth About Moving Others Online

Authors: Daniel H. Pink

Tags: #Psychology, #Business

The very idea of leaders subordinating themselves to followers, of inverting the traditional pyramid, made many people uncomfortable. But Greenleaf’s philosophy excited many more. Those who embraced it learned to “do no harm,” to respond “to any problem by listening first,” and to “accept and empathize” rather than reject. Over time, companies as diverse as Starbucks, TD Industries, Southwest Airlines, and Brooks Brothers integrated Greenleaf’s ideas into their management practices. Business schools added Greenleaf to their reading lists and syllabi. Nonprofit organizations and religious institutions introduced his principles to their members.

What helped servant leadership take hold wasn’t merely that many of those who tried it found it effective. It was also that the approach gave voice to their latent beliefs about other people and their deeper aspirations for themselves. Greenleaf’s way of leading was more difficult, but it was also more transformative. As he wrote, “The best test, and the most difficult to administer, is this: Do those served grow as persons? Do they, while being served, become healthier, wiser, freer, more autonomous, more likely themselves to become servants?”

21

The time is ripe for the sales version of Greenleaf’s philosophy. Call it servant selling. It begins with the idea that those who move others aren’t manipulators but servants. They serve first and sell later. And the test—which, like Greenleaf’s, is the best and the most difficult to administer—is this: If the person you’re selling to agrees to buy, will his or her life improve? When your interaction is over, will the world be a better place than when you began?

Servant selling is the essence of moving others today. But in some sense, it has always been present in those who’ve granted sales its proper respect. For instance, Alfred Fuller, the man whose company gave Norman Hall his unlikely vocation, said that at a critical point in his own career, he realized that his work was better—in all senses of the word—when he served first and sold next. He began thinking of himself as a civic reformer, a benefactor to families, and “a crusader against unsanitary kitchens and inadequately cleaned homes.” It seemed a bit silly, he admitted. “But the successful seller must feel some commitment that his product offers mankind as much altruistic benefit as it yields the seller in money.” An effective seller isn’t a “huckster, who is just out for profit,” he said. The true “salesman is an idealist and an artist.”

22

So, too, is the true person. Among the things that distinguish our species from others is our combination of idealism and artistry—our desire both to improve the world and to provide that world with something it didn’t know it was missing. Moving others doesn’t require that we neglect these nobler aspects of our nature. Today it demands that we embrace them. It begins and ends by remembering that to sell is human.

SAMPLE CASE

Serve

Move from “upselling” to “upserving.”

One of the most detestable words in the lexicon of sales is “upselling.” You go to the sporting goods store for basic running shoes and the salesperson tries to get you to buy the priciest pair on the shelf. You purchase a camera and the guy behind the counter presses you to buy a kit that’s no good, accessories you don’t want, and an extended warranty you don’t need. Once, when ordering something online, before I was able to check out, the site pelted me with about half a dozen add-ons in which I had no interest—and when I looked at the Web address, it read http://www.nameofthecompany.com/upsell. (I quit the transaction there—and never bought anything from that operation again.)

Sadly, many traditional sales training programs still teach people to upsell. But if they were smarter, they’d banish both the concept and the word—and replace it with a far friendlier, and demonstrably more effective, alternative.

Upserve.

Upserving means doing more for the other person than he expects or you initially intended, taking the extra steps that transform a mundane interaction into a memorable experience. This simple move—from upselling to upserving—has the obvious advantage of being the right thing to do. But it also carries the hidden advantage of being extraordinarily effective.

Anytime you’re tempted to upsell someone else, stop what you’re doing and upserve instead. Don’t try to increase what they can do for you. Elevate what you can do for them.

Rethink sales commissions.

Even after reading this book, you might still believe that traditional salespeople just aren’t like the rest of us. You and I have a mix of motives, many of them high-minded—but not those folks who sell household appliances or home security systems. They’re different. They are—and here’s an adjective I hear a lot—“coin-operated.” (Slip a quarter in their slot and they’ll do a little dance. When time runs out, insert another coin or they’ll stop dancing!) That’s why we usually rely on sales commissions to motivate and compensate people in traditional sales. It’s the best—perhaps the only—way to get them to move.

But what if we’re wrong? What if we offer commissions largely because, well, we’ve always offered commissions? What if the practice has so cemented into orthodoxy that it’s ceased being an actual decision? And what if it actually stands in the way of the ability to serve?

That’s what Microchip Technology, a $6.5 billion American semiconductor company, suspected. It once paid its sales force in accordance with the industry standard—60 percent base salary, 40 percent commissions. But thirteen years ago, Microchip abolished that scheme and replaced it with a package of 90 percent base salary and 10 percent variable compensation tied to company growth. What happened? Total sales increased. The cost of sales stayed the same. Attrition dropped. And Microchip has rung up profits every quarter since—in one of the most brutally competitive industries around.

From giant multinationals like GlaxoSmithKline to small insurance companies in Oregon to software start-ups in Cambridge, England, many companies are questioning this long-established practice, implementing new strategies, and seeing great results. They’re finding that paying their sales force in other ways has many virtues. It eliminates the problem of people gaming the system for their own advantage. It promotes collaboration. (If I get paid only for what I sell, why should I help you?) It spares managers the time and burden of resolving endless compensation disputes. Most of all, it can make salespeople the agents of their customers rather than their adversaries, removing a barrier to serving them thoroughly and authentically.

Should every company forsake sales commissions? No. But simply challenging the orthodoxy can be healthy. As Microchip’s vice president of sales told me: “Salespeople are no different from engineers, architects, or accountants. Really good salespeople want to solve problems and serve customers. They want to be part of something larger than themselves.”

Recalibrate your notion of who’s doing whom a favor.

Seth Godin, the marketing guru and one of the most creative people I know, has a great way of explaining how we categorize our sales and non-sales selling transactions. We divide them, he says, into three categories.

We think, “I’m doing you a favor, bud.” Or “Hey, this guy is doing me a favor.” Or “This is a favorless transaction.”

Problems arise, Godin says, “when one party in the transaction thinks he’s doing the other guy a favor . . . but the other guy doesn’t act that way in return.”

The remedy for this is simple and it’s one we can use in our efforts to move others: “Why not always act as if the other guy is doing the favor?”

This approach connects to the quality of attunement—in particular, the finding that lowering your status can enhance your powers of perspective-taking. And it demonstrates that as with servant leadership, the wisest and most ethical way to move others is to proceed with humility and gratitude.

Try “emotionally intelligent signage.”

You probably noticed that many examples in this chapter—from the Kenyan

matatu

s to Il Canale’s pizzeria—involved signs. Signs are an integral part of our visual environment, but we often don’t employ them with sufficient sophistication.

One way to do better is with what I call “emotionally intelligent signage.” Most signs typically have two functions: They provide information to help people find their way or they announce rules. But emotionally intelligent signage goes deeper. It achieves those same ends by enlisting the principles of “make it personal” and “make it purposeful.” It tries to move others by expressing empathy with the person viewing the sign (that’s the personal part) or by triggering empathy in that person so she’ll understand the rationale behind the posted rule (that’s the purposeful part).

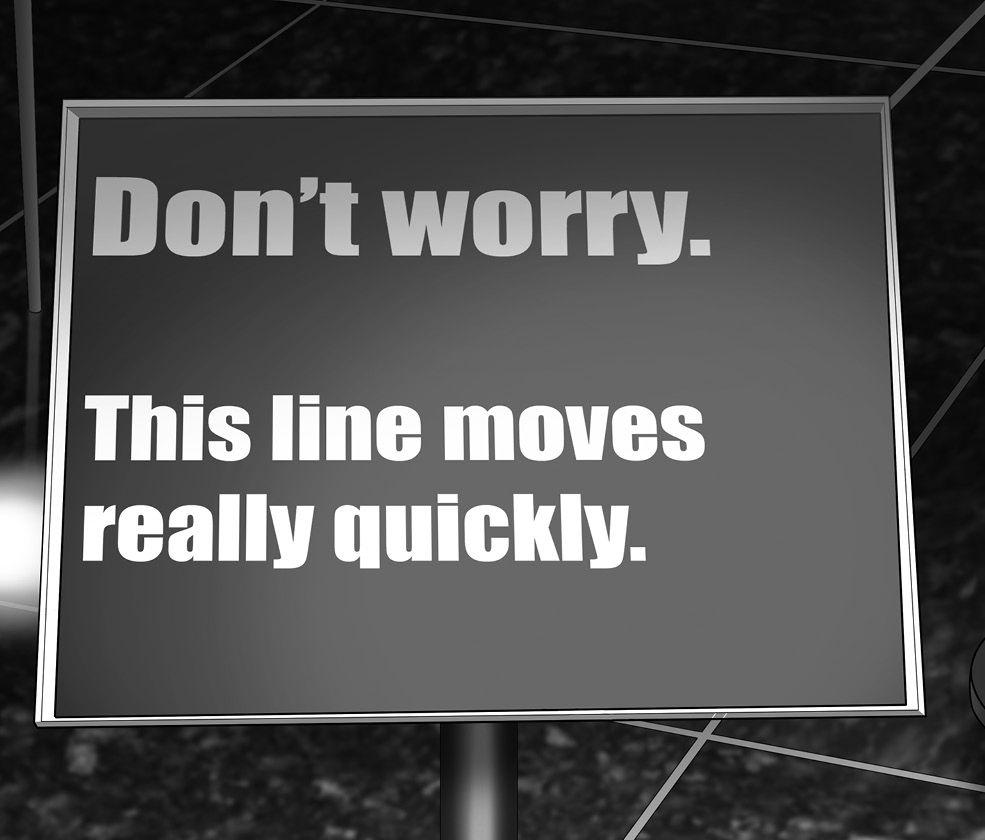

Here’s an example of the first variety. A few years ago, my family and I were visiting a museum in New York City. Shortly after we arrived, several of the smaller family members reported feeling hungry, which forced us to spend some of our limited time roaming a cafeteria looking for pudding rather than walking the museum looking at pictures. When we arrived at the eatery, the line to get food curled around a corner like an anaconda. I grimaced, thinking we’d be there forever. But moments after unscrunching my face, I saw this sign:

My cortisol level dropped. The line turned out not to be nearly as long as I feared. And I spent my short wait in a better mood. By empathizing with line-waiters—making it personal—the sign transformed the experience of being in that space.

For an example of the second variety of emotionally intelligent signs, I simply visited a neighborhood near my own in Washington, D.C. On one busy corner is a small church that sits on an enormous lawn. Many people in the area walk their dogs. And the combination of lots of dogs and a giant expanse of grass can lead to an obvious (and odorous) problem. To avert that problem, that is, to move dog-walkers to change their behavior, the church could have posted a sign that merely announced its rules. Something like this, for instance, which I’ve doctored a bit from the original:

However, the church took a different approach and posted the following sign instead:

By reminding people of the reason for the rule and trying to trigger empathy on the part of those dog-walkers—making it purposeful—the sign-makers increased the likelihood that people would behave as the sign directed.

Now your assignment: Take one of the signs you now use or see in your workplace or community and recast it so it’s more emotionally intelligent. By making it personal, or making it purposeful, you’ll make it better.

Treat everybody as you would your grandmother.

Yehonatan Turner, the Israeli radiologist who led the photo study, told

The New York Times

that the way he first dealt with the impersonal nature of his job was to imagine that every scan he looked at was his father’s.

You can borrow from his insight with this simple technique for moving others. In every encounter, imagine that the person you’re dealing with is your grandmother. This is the ultimate way to make it personal. How would you behave if the person walking into your car lot wasn’t a stranger but instead was Grandma? What changes would you make if the employee you’re about to ask to take on an unpleasant assignment wasn’t a seemingly disposable new hire but was the woman who gave birth to one of your parents? How honest and ethical would you be if the person you’re corresponding with via e-mail wasn’t a onetime collaborator but was the nice lady who still sends you birthday cards with a $5 bill tucked inside?