Tori Amos: Piece by Piece (35 page)

Read Tori Amos: Piece by Piece Online

Authors: Tori Amos,Ann Powers

John Witherspoon and I have really been able to kind of understand this one. One night it became so clear to both of us because we both had the same case of the flu. I went onstage feeling just like he did. A few hours later when I came back offstage he saw me, I saw him, and we got it. I was on fire and had sweated out the ghoulies completely and he was sneezing and shivering, doubled over. I was moving through it, because music does have the power to move things. And I was able to break through.

There is a tradition of traveling troubadours, bards and their companions, that goes back to the beginning of music and storytelling. A small group of people would make its way from encampment to encampment, through wars, through peacetimes, to sing of the news that they knew. Sometimes certain dictums prevented certain subjects from being discussed. That's why a particular set of symbols runs through art during some historical periods. Some people knew what these symbols represented, but because of the threat of being killed, iconography had to be used. This was its own language—pre-gangsta. It was part of a bard's art form, and still is.

I find that today, like the old troubadours, we pick up information on the road. If we're playing Seattle on a Friday night, what we bring to Portland the next night will contain the information we collected in Seattle. By the time we reach San Francisco, we will have added more to our palette. Even though compositionally the palette is ever changing and is at the center of my process, it's not the same as the revolving palette I use when I'm writing new works. What I do use is what I term the Road Labyrinth Palette. It's a thread that remains unbroken from show to show. The performances can connect, so that once you get to Dallas, you can pull from the London show with the snap of a finger. All the set lists are cataloged in a computer, along with the themes for each show—weird, sexual, religious-repressed shows, or hostile, political, in-reaction-to-world-events shows. From the information I've categorized, including every word of every song I've written, I can build a narrative that interconnects within the subtext. This is just an example of how threads are used to weave one night's live performance tapestry. This is what harkens back to going from campfire to campfire across Ulster—what you hear in one village you take with you to the next.

Some things are consistent in this world. The main ones for me are that a mother's love is a mother's love, romance is romance, and that a musician—be it 2005 B.C. or A.D. 2005—must play and that a road dog is a road dog is a road dog. Hopefully you will have felt this if you've toured with my crew.

CANVAS:

“Martha's Foolish Ginger”

I started writing this one years ago, when I was close to the water, on tour somewhere. I had only a seed idea of it, but it has stayed with me for a while now. On the “Lottapianos” tour during the summer of 2003,

when we were in San Francisco, I was by the Bay again. The song began to come back to me. Once I began to understand the female character I needed to embody I was able to finish this piece, but a real turning point was when I was able to see the character's boat, which she called

Martha's Foolish Ginger

, sailing out of the Bay and into the Pacific Ocean.

ANN:

Venus: the brightest planet in the universe. Venus, the goddess whom the ancient Romans first imagined as a simple, primal force governing fertility, transformed by Rome's encounter with the Greeks (who called her Aphrodite) into one of the most complex characters in the world pantheon. That Venus, the one the world remembers, is exacting and generous, innocent and manipulative, the patron of marriage who tore the world apart by leading the hero Paris and the beauty queen Helen into lethal adultery. The embodiment of physical attraction in all its chaotic power, Venus is unavoidable. She governs what the art critic Dave Hickey once called “the iconography of desire”: what strikes the soul as beautiful, no matter whether it's morally proper or politically correct.

Because she exists beyond the realm of rules, Venus can take whatever shape suits the moment in which she enters. Her name has been given to female figures as wildly different as the squat, heavy prehistoric Venus of Willendorf; the gorgeous, armless Greek ideal known as

Venus de Milo;

the Renaissance wraith Sandro Botticelli painted in his

Birth of Venus;

the “Venus Hottentot,” an African woman exhibited as a freak to a racist British public in the early 1800s; the Venus flytrap, the sexy southern plant that snaps up its prey in its “jaws;” Blonde Venus, the Hollywood version embodied by Marlene Dietrich and Marilyn Monroe; and even Sailor Venus, a Japanese anime character who flutters the hearts of today's teenage boys. Far from pure, Venus leads us into the thicket of social prejudices, historic assumptions, and personal fascinations where desire grows, seemingly beyond governance.

In a world where few can agree on the power of the gods, popular culture is where the desire Venus personifies finds a home. Images saturate our consciousness, ceaselessly emanating from movie, television, and computer screens, billboards, and magazines. Beauty, always an asset for artists, is now an unavoidable subject. The challenging task is to take control of one's own beauty, to decide

what it can be, rather than just giving in to the whims of the fashion industry and other marketing forces.

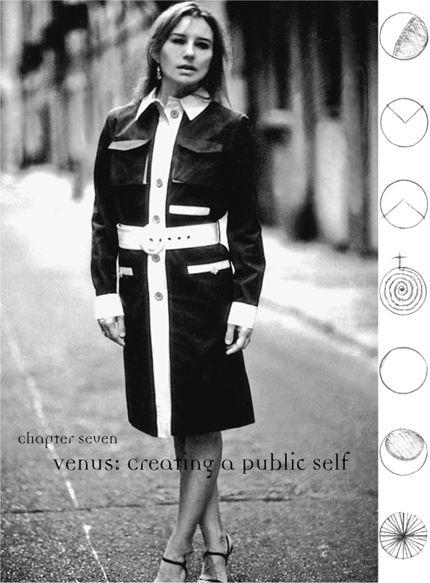

Tori Amos has fought to claim her own sense of beauty over the course of her career. A musician first, and always a feminist, she has sought ways to capture desire without becoming its object. What she wears, how she poses for a photograph, the light she emits when she smiles: these gestures are not insignificant. She has come to learn the importance of taking care with even the small details of a public image, as she's spent two decades coming to terms with Venus's whimsical command.

[TORI:

First I'd like to say that I believe that every person creates a public image, which I address in the second part of this chapter. Because Ann had a very clear vision about wanting to talk about a performer's public self, I wanted to give her “the floor;” I guess, more accurately, I wanted to give her “the pages” to express her view of a performer's public self. Since she has had to interview the likes of hundreds of my kind and kindred, musician/performers, I felt she has a valid perspective on a performer's public self. After all, she has certainly seen more than I have. The first half of this chapter resulted from the ongoing conversation between us; the second half is my considered response to what we discussed.]

Every performer has to create a public image, and if you're a woman, you can't pretend it's a matter of small importance to your career. Try slouching around in your gym clothes and the record label will be after you, the press will consider it either a statement or a mistake, even your fans will think you've lost your touch. I had a few choices when I started to find my way as Tori Amos. I could have done what many artists do now, taking

whatever was offered from the fashion industry representatives who put those gowns on the award show runways, and in music videos, and on album covers. Or I could take charge of my image as another aspect of my art. For me, the choice was easy. But the implementation of this has naturally been a challenge.

If you're going to put out art that's sonically fresh, why wouldn't you be open to art that's visually fresh? I do consider the designers who make the clothes I wear to be artists. Still, it takes a lot of time and effort. And money. But everybody shops, whether you're a performer or a student or a secretary. It's just a matter of putting the time aside, the money, and surrounding yourself with visual artists whose sense of style fits you like a good pair of stretch jeans. I work with a team for whom fashion is a full-time thing. My advisers on matters of style—Mark dubbed them “the Glam Squad” a few years ago—know things I could never know. I live the musical life, I'm a musician mom, this is all I do. I write songs every day. Nobody will hear most of them. Nobody will see 90 percent of the things my crew suggests I wear. But it's a flow we create.

We take pictures of every performance and appearance so I'll know where we were that day and how much exposure any given piece has had. I'm only taking so many wardrobe cases with me whenever I travel, so I have to make choices. I let only my own stylist buy things, because she knows what we've done. When she's on another continent she liaises with Chelsea, and after all these years that works well, too.

One thing is a necessity—good shoes. Designers and stylists lend clothes all the time, but I don't like to borrow shoes. Because I'm playing, and I'll wreck them. So I have to buy them, and they are not cheap. I need many different kinds of shoes—a certain kind for playing live, a different kind for television appearances (they can't be too low), and then some for just kicking around. If I've worn a pair on a nationally broadcast show, I

can't wear them again for a similar show. It's a big part of playing, the right shoes. I reassure my hands of that all the time.

Sometimes the musician side of me rebels against the fashion side of the pop music world and I just want to wear jeans and sweatshirts, the way I did before I made records, the way many male musicians still do most of the time. When I get into that space, I start buying lots and lots of visual art books. I need an entry point back into the visual side of my work. There was a period, in the late 1990s, when I became really tired of the fashionista phenomenon. Designers, brand makers, and models had been taking over the house like cockroaches. You know when you see a house and it's covered in a kind of tent because it's being fumigated? Around that time, I needed to be fashiongated. I did go back to jeans and a T-shirt—though they were always the right jeans and T-shirt, the ones that made a statement, however quiet. It's very hard to figure out the balance.

If you don't keep pulling in from the visual artists who are making pieces you can wear, then what happens is you stop relating to people in some way. Obviously, for a composer the content has to be at the center, but I don't think you can let either slide. After you've been in it for a while your image can become humdrum. Yet many female musicians develop the opposite tendency, even those who are legitimate composers or virtuosos. Too much energy has been put on the image and not enough on the content. Enough already …

The people who are performers first, like Madonna, have this sussed, and we can learn from them. They're thinking about the look and the video

before

the content, and their music often originates in direct connection with their image. Madonna's sound was made for the dance floor when she epitomized the New York club kid; it got a bit closer to rock when she started presenting herself that way, connected with R&B when

her image became softer again, went New Age techno when she got into spirituality, and so on. Fashion has become a part of the musical exploration and experience. Missy Elliott has done a similar thing; so has Gwen Stefani. Their image is essential and extremely tight. If they get it wrong, critics castigate them for it—they are known for their style.

Sometimes artists get overconfident about their content, and that's their downfall. But musicians can make the opposite mistake. I'm including myself here, too, so let's be clear. They put on an image without thinking of how it relates to their music and forget that live performance is also visual. If they are uncomfortable with this side of things, sometimes they go out there trying to make a joke of it all. Sometimes you wish these guys would just try pushing a “Krusty the Clown” image, because at least that would be funny. You can't run away from visual expression. You can't hide behind the “I'm all about the content” line forever. You may get away with that for one record, if you're hot. But style will choose you if you don't choose it. And it takes even more energy to have a nonstyle, because you have to work very hard to be the paradox of what's in fashion. If you can pull this off—this “all about the content” look—then you could become known as an anti–fashion victim.