Tracking Bodhidharma (6 page)

Read Tracking Bodhidharma Online

Authors: Andy Ferguson

As we ride, Yaozhi talks to me about other key differences between Japanese and Chinese Buddhism. In particular, many Japanese Buddhist monks marry and have children. Japanese government reforms carried out during the late 1800s directed that Buddhist monks could marry (in part to make the country stronger in an age of imperial conquest), and ultimately this practice was widely adopted by heretofore celibate monks in that country. Japanese monks could not only marry but might even own temples as personal property. Through selling religious

services on the venue of these properties, they derived personal income. So by allowing monks to marry, own property, and earn money, the line between Buddhist monks and lay people became blurred. Through this blurring of a clear distinction between the life of a Buddhist monk and a lay person, the status of the clergy was naturally degraded, its sacred legitimacy placed in doubt. Thus the word

priest

was adopted to describe them and help differentiate their spiritual status from that of the lay community.

services on the venue of these properties, they derived personal income. So by allowing monks to marry, own property, and earn money, the line between Buddhist monks and lay people became blurred. Through this blurring of a clear distinction between the life of a Buddhist monk and a lay person, the status of the clergy was naturally degraded, its sacred legitimacy placed in doubt. Thus the word

priest

was adopted to describe them and help differentiate their spiritual status from that of the lay community.

In the course of our conversation, Yaozhi says that the differences between Japanese and Chinese Buddhism became embarrassingly apparent during the late 1980s when certain Chinese monks went to live in Japan. Yaozhi says, with a slight grin,“One person went and three came back.” In other words, some Chinese monks traveled to Japan to live and practice their religion and returned to China with a wife and child.

Yaozhi tells me that the Chinese Buddhist Association then spoke to these issues by stating that “Japanese Buddhism is Japanese Buddhism, and Chinese Buddhism is Chinese Buddhism.” In other words, a clear demarcation would be made between practices in Japan and China, and China would adhere to its own tradition of demanding that “home-leavers” remain celibate.

While I was studying and sitting at San Francisco Zen Center during much of the 1990s, I didn't give a lot of thought to the differences between Japanese and Chinese Zen. If anything, I simply thought that the way the practice is done in Japan and the West is more modern and nonsexist than the traditional way in China. I think my views coincided with new prevailing social mores that came from the '60s, and seemed to be a proper and “modern” perspective.

But my perspective on this question began to change when I visited Chinese Zen temples in earnest during the 1990s. On my second or third visit to a temple where a famous ancient Zen master named Zhaozhou (Japanese name Joshu, 778â897) once lived and taught, the issue came to the fore.

At the time of my visit, the abbot of the temple was a monk named Jinghui (“Pure Wisdom”), a prominent teacher now widely known in China. The temple's head monk, whose position was immediately under Jinghui in the temple's administration, was named Minghai (“Bright Sea”). Bright Sea was immensely welcoming and helpful each time I

came to the monastery to visit. He is the same individual who set up my meeting with Yaozhi.

came to the monastery to visit. He is the same individual who set up my meeting with Yaozhi.

It was during one such visit to the monastery that Bright Sea invited me to give a talk to a class of Buddhist monks there. I asked him what he wanted me to talk about, and he said it would be good if I spoke about the development of Zen Buddhism in America. I reflected on this a moment, then told him I didn't really consider myself qualified to speak on this topic, since I was only somewhat familiar with only one Zen Center in the United States (San Francisco) and knew about others only through reading or occasional visits to a few places. Bright Sea assured me that what I knew would be enough for the talk.

In the end, the talk went badly. I told the sixty or seventy young monks assembled in the monastery classroom about various Zen centers in the United States, the names of their teachers, and how they mostly originated from lines of Japanese Zen teachers. I talked of what I knew about Shunryu Suzuki, the founder of San Francisco Zen Center, plus a Kamakura-based Japanese lineage derived from the Japanese teacher Yamada Roshi, and a few other Japanese teachers like Taizan Maezumi of Los Angeles. But I sensed as I gave the talk that my knowledge of the subject matter was entirely insufficient and I was definitely not connecting with the audience. The monks sat quietly with blank looks on their faces, and when I asked for questions, almost nothing was forthcoming.

When I finished speaking, Bright Sea thanked me and I returned to my guestroom in the monastery. I lay on my bed there, wondering about the deeply unsatisfactory feeling I carried away from my first attempt to communicate with a big group of Chinese monks. There was a knock on the door. I opened it to find a little monk standing there, looking at me rather timidly. He asked if he could ask a question. I said of course he could, and then he said, “Is it true that in America monks get married?” I was taken aback by the question, and it took me a few moments to realize its import, but then I managed to mumble something about how monks in America usually married persons of the opposite sex who were also monks or at least interested in Buddhism. This answer simply stumbled out of my mouth in an attempt to fill the void that the monk had exposed. When I told this story to someone later, they said the monk had simply pointed out the eight-hundred-pound gorilla in the classroom where I gave the lecture, as I had abjectly failed to notice it.

Our SUV is traveling in a nice shopping area. Yaozhi is explaining some points about how the Buddhist religion is surviving today, in the wake of the Cultural Revolution. He says that that event, although a tragedy for China on virtually every level, nonetheless provided Buddhism in China with one thing of value. For centuries, from the time of the Western Jin dynasty (265â316 CE) until the rule of Emperor Shun Zhi in the Qing dynasty (died 1661), monks in China were required to pass stringent examinations in order to enter the Buddhist orders. They needed to commit to memory long passages of Buddhist scriptures, plus they were required to understand and speak in an informed fashion on points of doctrine. Emperor Shun Zhi ended the examination system in a bid to have more people enter the Buddhist orders. The result, says Yaozhi, actually harmed Buddhism greatly. Without standards of knowledge, standards of conduct also declined, and improper behavior or practices reared their heads. After Japanese Buddhism underwent fundamental changes during the Meiji era in the late 1800s, changes that allowed monks to marry, inherit property, and so on, such phenomena started to spread and take root in China as well. I remember that some of the things Yaozhi is talking about were described in a book I read on pre-1949 Buddhist practices in China. The Cultural Revolution, says Yaozhi, caused harm to China, but it also had a certain beneficial effect. It allowed the Buddhist community there a chance to purify and reinvent itself, to reestablish stricter standards of conduct for its home-leaving monks. Yaozhi says this has been positive, as Buddhism has become ever more popular in China. Today, the need for Buddhism to provide a moral compass for society is recognized even by the nominally atheistic government. Accepting and following the traditional Buddhist precepts, the guidelines for moral behavior, is now seen as contributing to the rebirth of a “spiritual society.”

Suddenly, a large

paifang

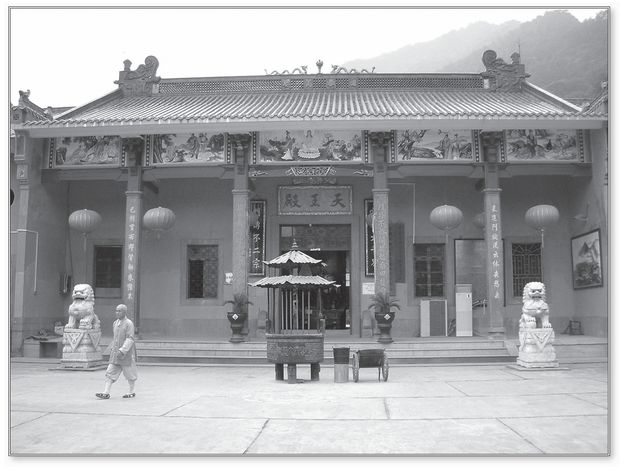

(an ornamental gate like the one where Bodhidharma came ashore) indicates we've arrived at Grand Buddha Temple, one of the five great Buddhist temples of Guangzhou. We exit the car on the traffic street and walk up a lane leading to the first hall of the temple. What greets us is typical of what one finds when entering a Zen temple in China, and is called the Heavenly Kings Hall.

paifang

(an ornamental gate like the one where Bodhidharma came ashore) indicates we've arrived at Grand Buddha Temple, one of the five great Buddhist temples of Guangzhou. We exit the car on the traffic street and walk up a lane leading to the first hall of the temple. What greets us is typical of what one finds when entering a Zen temple in China, and is called the Heavenly Kings Hall.

4. The Layout of a Traditional Chinese Temple

ZEN MASTERS OF OLD often talked in a manner that seems, at first blush, like a riddle. Take for example this old story about a Zen master named Linxi (pronounced

Lin-see

):

Lin-see

):

A monk asked Zen Master Linxi, “What is the essence of your teaching?”

The master said, “Mountains and rivers.”

The monk then asked, “Who lives among these mountains and rivers?”

The master said, “Behind the Buddha Hall. In front of the temple gates!”

This story doesn't make any sense unless you are familiar with some basic ideas of Zen Buddhism and also familiar with the typical layout of old Zen temples. The arrangement of the buildings in those temples, oddly, provides a basic lesson in Zen Buddhist psychology. The positions of the main halls and gates have special significance, and their symbolism is enhanced by the placement of the Buddhist icons and statues, or lack of such items, inside the halls.

To understand this we need to step back for a moment and look at a little of the philosophical background of Zen Buddhism. Different Indian Buddhist traditions influenced the growth of Zen in China, but the Yogacara school of Indian Buddhism was a key contributor to the Zen world view. A fundamental idea in Yogacara (I'll call adherents of Yogacara the “Yogis”) philosophy was called the Three Natures

(San Xing).

These “natures” were three different ways of looking at human perception, the way the mind observes the world.

(San Xing).

These “natures” were three different ways of looking at human perception, the way the mind observes the world.

There was one other school of Buddhist philosophy that had a big influence on Buddhism during Bodhidharma's time. That school was called the Madhyamaka school, and it emphasized the idea of “emptiness.” I'll call people who emphasized this idea the

“Empties” from now on, because we'll see their influence come up again in Zen and Buddhist discussions. The point to remember is that there were Yogis (people emphasizing “mind” as their essential idea) and “Empties” (people emphasizing “emptiness” as the essential idea) in the Buddhist tradition of Bodhidharma's age.

“Empties” from now on, because we'll see their influence come up again in Zen and Buddhist discussions. The point to remember is that there were Yogis (people emphasizing “mind” as their essential idea) and “Empties” (people emphasizing “emptiness” as the essential idea) in the Buddhist tradition of Bodhidharma's age.

Â

FIGURE 6. Heavenly Kings Hall at Yun Men Temple, Guangzhou Province.

Bodhidharma's famous teaching (at least it is credited to him) instructed people to observe the “nature of the human mind,” and this idea dovetails nicely with the Three Natures teaching. So what are the Three Natures that correspond to Zen temple architecture? We'll take a quick walk through an old Zen temple to make this clear.

THE FRONT HALL OF HEAVENLY KINGS: THE “NATURE” OF SELF AND OTHERThe main front hall of Zen temples, called the Heavenly Kings Hall, is a representation of the “first nature” of consciousness (for anyone who cares, the Sanskrit term for this “nature” is

parikalpita

). The hall contains an arrangement of statues of certain deities toward whom Chinese

people often prayed (and still do) to receive benefits and blessings. The “Heavenly Kings” referred to in the name of the hall are four mythical deities that guard the “four continents” of the world, as believed and taught in the ancient Upanishad tradition of India. Each statue of a heavenly king occupies one of the four quadrants of the hall. At the center of the hall, facing you as you come in the front door, there is typically a statue of the big fat happy Buddha widely recognized in both East and West. Even if you've never visited a Chinese temple you've seen this happy fat Buddha, named Maitreya (in Japan, this Buddha is called “Hotei”), in East Asian restaurants or your local garden supply where he's often sold as a yard ornament. For centuries, Chinese people have prayed to the deities in this hall for blessings and assistance. The “nature” of people's relationships with these deities is that of “self and other.” This can be understood as “I'm here and there's a deity over there that I'm praying to, and I want some blessing to come from him.” This “self” and “other” relationship characterizes normal human thinking about the world and how we see it. This sort of thinking also typifies usual religious belief and practice.

parikalpita

). The hall contains an arrangement of statues of certain deities toward whom Chinese

people often prayed (and still do) to receive benefits and blessings. The “Heavenly Kings” referred to in the name of the hall are four mythical deities that guard the “four continents” of the world, as believed and taught in the ancient Upanishad tradition of India. Each statue of a heavenly king occupies one of the four quadrants of the hall. At the center of the hall, facing you as you come in the front door, there is typically a statue of the big fat happy Buddha widely recognized in both East and West. Even if you've never visited a Chinese temple you've seen this happy fat Buddha, named Maitreya (in Japan, this Buddha is called “Hotei”), in East Asian restaurants or your local garden supply where he's often sold as a yard ornament. For centuries, Chinese people have prayed to the deities in this hall for blessings and assistance. The “nature” of people's relationships with these deities is that of “self and other.” This can be understood as “I'm here and there's a deity over there that I'm praying to, and I want some blessing to come from him.” This “self” and “other” relationship characterizes normal human thinking about the world and how we see it. This sort of thinking also typifies usual religious belief and practice.

Â

FIGURE 7. Heavenly Kings Hall Typical Layout.

The second main hall of a traditional Zen temple, which corresponds to the second of the Three Natures, is the “Buddha Hall.” The “nature” associated with this hall can be translated as “Dependent Co-arising Nature” (Sanskrit:

paratantra

). Note that

para

means “supreme” and

tantra

originally meant “to weave,” which we may understand by extension to mean “intertwining,” a word with obvious links to the tantric

sexual practices of some other traditions. In this hall we find “Dependent Co-arising” to be Buddhism's view of the ultimate “intertwining.” Here, visitors typically find one to three statues of different types of Buddhas, plus other statues of Buddha's disciples as well as bodhisattvas. The latter, unique to East Asian Mahayana (“Great Vehicle”) Buddhism, are honored as compassionate deities that appear in the world to relieve suffering. Typically, in ancient times and today, at the very center of the Buddha Hall sits a statue of the historical Buddha, also named Shakyamuni (“Wise One of the Shakya Clan”), who lived in India in 500 BCE or so. “Dependent Co-arising,” the second “nature” of the Three Natures, is the idea that consciousness is a unitary experience that is divided by the brain into “self” and “other.” Although there is no division of the sensations in the five senses, due to our biological evolution and adaption, the brain naturally separates the sights, smells, and other sensations of our senses, as either part of the “self” that is thought to exist in our body, or “other,” things that are outside of us. Naturally, our biological evolution demanded that we recognize what needed to be preserved and protected so procreation could happen. The teaching here is that the division between the “self” and “other” is, despite our attachment to it, a fiction created by our brain. At this point I won't go into all the ramifications or a detailed explanation of this. Traditionally, Zen regards meditation as the main way for people to see and understand this “nature,” the mind.

paratantra

). Note that

para

means “supreme” and

tantra

originally meant “to weave,” which we may understand by extension to mean “intertwining,” a word with obvious links to the tantric

sexual practices of some other traditions. In this hall we find “Dependent Co-arising” to be Buddhism's view of the ultimate “intertwining.” Here, visitors typically find one to three statues of different types of Buddhas, plus other statues of Buddha's disciples as well as bodhisattvas. The latter, unique to East Asian Mahayana (“Great Vehicle”) Buddhism, are honored as compassionate deities that appear in the world to relieve suffering. Typically, in ancient times and today, at the very center of the Buddha Hall sits a statue of the historical Buddha, also named Shakyamuni (“Wise One of the Shakya Clan”), who lived in India in 500 BCE or so. “Dependent Co-arising,” the second “nature” of the Three Natures, is the idea that consciousness is a unitary experience that is divided by the brain into “self” and “other.” Although there is no division of the sensations in the five senses, due to our biological evolution and adaption, the brain naturally separates the sights, smells, and other sensations of our senses, as either part of the “self” that is thought to exist in our body, or “other,” things that are outside of us. Naturally, our biological evolution demanded that we recognize what needed to be preserved and protected so procreation could happen. The teaching here is that the division between the “self” and “other” is, despite our attachment to it, a fiction created by our brain. At this point I won't go into all the ramifications or a detailed explanation of this. Traditionally, Zen regards meditation as the main way for people to see and understand this “nature,” the mind.

Other books

Soulfire by Juliette Cross

Unlocked by Karen Kingsbury

Something Magic This Way Comes by Sarah A. Hoyt

Piranha Assignment by Austin Camacho

Daughters of Spain by Plaidy, Jean, 6.95

The Survivors of the Chancellor by Jules Verne

Legenda Maris by Tanith Lee

The Valentine Wedding Dress by Sherryl Woods

The Occupation of Emerald City: The Worker by Brosky, Ken

The Mum-Minder by Jacqueline Wilson