Train Tracks (13 page)

Authors: Michael Savage

Â

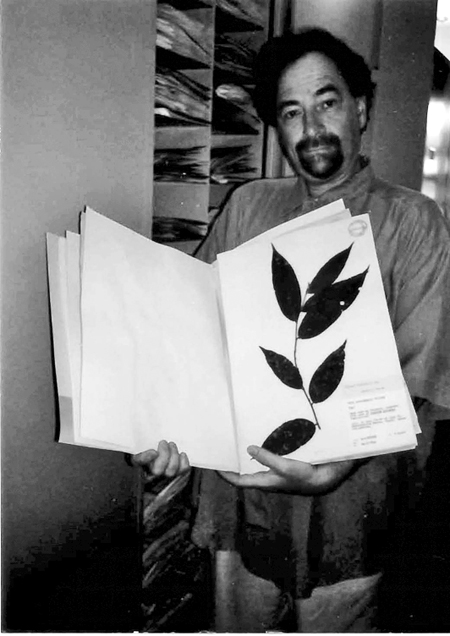

Kew Gardens, London. One of the hundreds of my

ethnobotanical specimens in the permanent collection.

J.

Weiner

Â

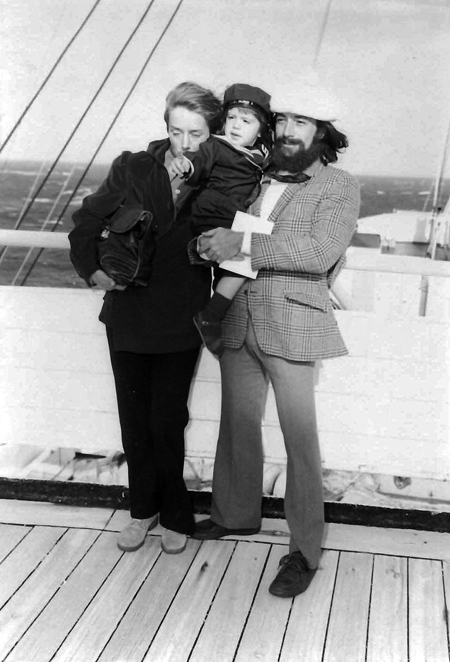

Arcadia.

Honolulu to Vancouver (1971).

Â

Father and daughter.

Â

Father and son at the gun range (1980s).

Â

Mama Savage in her little Queens kitchen where

she cooked for an army (1970s).

Â

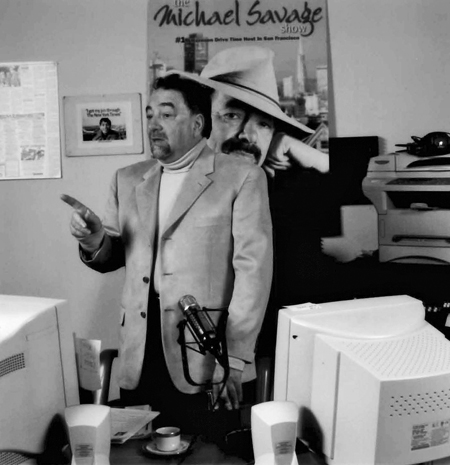

In one of my home studios (2002).

Leon Borensztein

Â

The night we all lost. Election Eve (2008).

Leon Borensztein

The Electric Blue Saddle-Stitched Pants

I

n the seventh grade, my mother bought me the most incredible pants. We didn't have a lot of money, but she knew I wanted these pants really bad. It was the “Elvis era.” Mama Savage saved and bought me a pair of electric blue saddle-stitched pants. I wore them to schoolâI thought I was Elvis himself.

On the very first day, a bigger, older kid just happened to be wearing the same pants, and naturally, we got in a scuffle. He pushed me down and my gorgeous Elvis pants were ripped in the knee. I thought it was the end of the world because these were the most expensive, beautiful pants I had ever had in my life. So, the rest of the day, I couldn't sit through the classes. Whatever the teacher said, my mind was somewhere else. My heart was pounding:

How am I going to tell my mother

?

How am I going to tell my mother?

So, I came home with the pants, hiding the rip under my coat. I said, “Ma, I ripped my pants.” She didn't get mad. She said, “Let me see them. Don't worry about it.” I said, “You're not going to tell Dad, are you?” She said, “No, don't worry about it.” So, all night long I couldn't sleep.

The next day the women were talking it over, sitting around the little table in that little house in Queens, and they were moving the crumbs around with their bread knives and talking. They decided what to do: They took the pants to a certain tailor, and the word came back: “Don't worry, Michael. The pants can be weaved.”

Now, I didn't know what “the pants can be weaved” meant. I don't think they do that anymore because clothing has become something different than it was then. We throw everything away. But I knew from that moment on that everything would be goodâand it was. The pants were weaved.

That's what a mother's for, I guess: to fix everything but a broken heart.

The Fly in the Tuna

W

hen I was a wee lad, that would be between the ages of eight or nine, my father stood up for me. Skinny, polo shirt, dungarees, spring or summer, Saturday, probably working with Dad in the little store down there on New York's Lower East Side.

He would send me for lunch out on the mean streets in order to toughen me up, because he thought I was too soft growing up in the suburbs. He insisted that I go walk alone in those horrible streets and learn how to fend for myselfâdodging the garbage, the rats, the thugs, and whatever else was in the street. It was only dangerous up to a point. It's not as dangerous as some kids face today in the average housing project, but it was a bad neighborhood in those daysâand certainly different than the “Garden of Queens,” in New York, where we were living.

So, he would send me for lunch. There was a dairy restaurant, where they had dairy only and no meat. They would serve tuna fish salads, whatever. It was filthy dirty. If you didn't want the meat from Katz's Delicatessen that was down the street, this place was a “no meat joint.” So he sent me for a tuna sandwich. I came back with the tuna sandwich, and my father opened it up and there was a fly in it. He was enraged, so he took me by the hand. He was mad that they would give this kid, his son, a sandwich with a huge fly in the middle of it. He assumed they did it on purpose. They probably did; they were spiteful.

He took me by the hand, put down his work making lamps or whatever he was putting together for the day, dragged me up the street, with his neck bulging, veins bulging, eyes bulging. He went into the dairy restaurant and screamed at the guy, “How dare you give my son a sandwich with a fly in it!” The guy said, “Let me see the sandwich.” He opens it and sees the fly in it. He says to my father, “I didn't charge him any extra. What are you yelling about? I didn't charge him for the fly.” You know, it's an old joke, but it wasn't funny.

In a way Dad was standing up for me, I guess. I think that's the one time I could say “quasi” standing up for me, because, other than thatâtruthfully, I meanâhe even took our dog Tippy's side after the dog tore my leg open, now that I think about it. It was like an Abraham-and-Isaac relationship: I think if he had the rock and knife, I wouldn't be here today. Thank God he didn't collect box cutters and that there were no large rocks in the backyard. That's all I can say.

Tough High School Geometry Teacher: Two Fingers on His Right Hand

I

had a geometry teacher in high school with only two fingers on his right hand. He was a tough guy. He was an Irishman and real tough, but a very good teacherâthe kind of teacher who made you come up to the blackboard and perform. If you didn't, he ridiculed you. He didn't curse you out, but he called you a dummy. As you stood there sweating, he might say, “Now what's the matter with you today? Is your brain not functioning?”âthat kind of thing. Believe me, you didn't want to wind up in front of that blackboard not knowing your stuff, because you didn't want to be humiliated in front of your peers.

Today, of course, they take any moron off the street, any idiot who has one eye going up, one eye going down, who can hardly speak, and they tell you he's smarter than you are. If you dare be smarter than him, you go to the back of the class. But in those days, it was very clear: If you were smart, you were smart. If you were stupid, you were dumb, and that was the end of it. No one changed anything.

He had a left hand with five fingers and a right hand with two fingers. The two fingers were stubs, but he could still put chalk on the board. When he said to you, “The midterm exams are back,” he would read out every name and every scoreâpublicly. Now, why do you think he did it? Because he understood that by doing well, you were proud of yourself and the other kids looked up to you; and, by doing poorly, you were ashamed of yourself and you would try to do better. But now, because the liberal nuts took over the schools, where they try to put perversion ahead of everything else, they have now taken dummies and tried to make them better than the “smarties.” Consequently, the schools can't even teach Johnnie how to add or readâand if Johnnie isn't smart enough and he can't focus at all, they put him on Ritalin to dope him up and turn him into a sissy and a dumbbell who can't do anything except sit in a cubicle for the rest of his life and possibly jump off a building when he's twenty-five.

Now, how Mr. W. lost his fingers is another interesting story. We all heard the rumors. It was whispered in the halls of the high school that he lost his fingersâand I'm not glorifying itâplanting a bomb for the IRA. Now, I don't know whether it was true, but it was certainly enough to make us understand not to mess around with this teacher, and we didn't. We respected him. Whether it was true or not is irrelevant. That's who we had for teachers in those days: many tough men, most of them vets from World War II.