Tranquility

Authors: Attila Bartis

Attila Bartis

Translated from the Hungarian by Imre Goldstein

archipelago books

English translation © 2008 Imre Goldstein

Originally published as

A nyugalom

by MagvetÅ, 2001 Budapest

Copyright © 2001 Bartis Attila

First Archipelago Books Edition, 2008

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced

or retransmitted in any form without prior

written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bartis, Attila.

[A nyugalom. English.]

Tranquility / by Attila Bartis ; translated from the Hungarian by Imre Goldstein.

p. ; cm.

ISBN

978-0-9800330-0-7

I. Goldshtain, Imri, 1938â II. Title.

PH

3213.

B

2976

N

9413 2008

894â².51134 â dc22Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 2008015344

Archipelago Books

232 Third St. #

A

111

Brooklyn,

NY

11215

www.archipelagobooks.org

Distributed by Consortium Book Sales and Distribution

www.cbsd.com

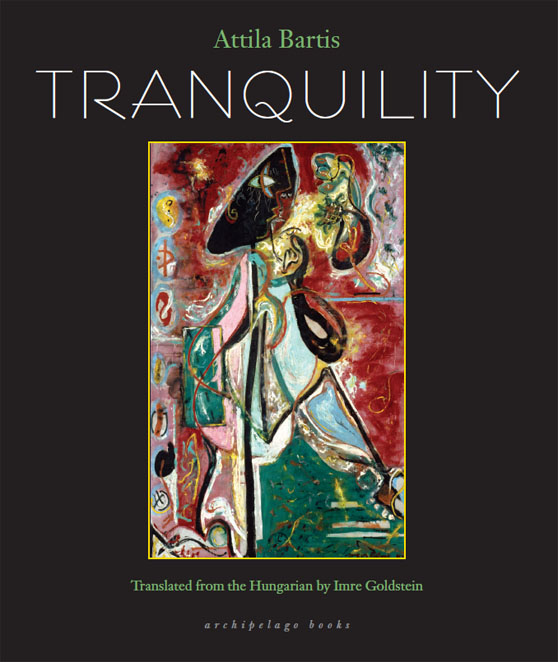

Cover Art: Jackson Pollack,

The Moon Woman

, 1942

Oil on canvas, 69 Ã 43 inches (175.2 Ã 109.3 cm)

inches (175.2 Ã 109.3 cm)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Peggy Guggenheim Collection, 1976

76.2553.141

This publication was made possible with support from Lannan Foundation, The National Endowment for the Arts, and the New York State Council for the Arts, a state agency. The work also received support from the Hungarian Book Foundation.

Contents

the

funeral was at eleven in the morning on Saturday, though I would have liked to have waited a few more days, in case Eszter showed up, but they wouldn't continue with the refrigeration, not even for extra payment. The woman in the office quoted some new regulation and then asked why not cremate the body; it would be cheaper and much more practical since I could pick a time convenient for everybody in the family, to which I replied that I would not incinerate my mother, let the funeral be on Saturday, and I paid in advance for the three days of storage; she gave me a receipt, entered casket number 704-Saturday-Kerepesi-cemetery into the delivery log, and then put some papers before me, showing with a ballpoint pen where to sign.

.   .   .

When the woman suggested cremation, I did waver for a moment because I remembered my mother's hysterical poses, “Look, that's how they sit up, all of them,” she would say, holding on to the chair by her bedside and showing

me how corpses sat up in the oven; a few months earlier she had seen a documentary on the subject and since then she would mention it almost every morning, and I'd say to her, don't worry Mother, you won't be cremated, and be careful you'll spill your tea; but in a few days she'd start all over again, that cremation was ungodly, and I knew she was afraid there would be no resurrection for cremated people, and that was really something, considering she had never in her damned life had anything to do with God. Lately she had demanded I swear she wouldn't wind up in a crematorium; she forbade me to burn her, to which I replied that I'd swear to nothing and since, luckily, she was still ambulatory, she should go to the notary's office and get a paper saying it was forbidden to burn her; that shut her up, because for fifteen years she'd been too scared to leave the apartment.

.   .   .

In short, for a moment I tried to visualize Mother sitting up in the oven, without holding on to a chair, but then I thought of Eszter, who might still come back, because I would have liked her to see the withered body, the nails bitten to the quick on the knobby fingers with the seven souvenir rings â from the Juliet of the Year souvenir ring through the Friends of Poetry souvenir ring all the way to the Moscow Festival souvenir ring â from which the gilding had long peeled off and, depending on whether they were made of copper or aluminum, stained the fingers green or black. I wanted Eszter to see the sticky straw-blonde hair on which the dye would become smeared more and more unevenly every year, and through which the ashen hue of the head's skin would glow dimly; and the breasts, made firm and taut again by rigor mortis, but which, way back then, after barely a month and a half of breast-feeding, she smeared with salt lest the nipples become elongated; but most of all I would have liked Eszter to see the dead countenance, the countenance that was in no way different from the live

one and whose bluish glimmer, as of Saturday morning, would begin to light up the grave that had been waiting empty for fifteen years â all because her eyes could not be shut.

.   .   .

There was no need for an obituary because for a decade and a half she had had no acquaintances, and I didn't want anybody, except Eszter, to come to the cemetery. I hate death notices; there were about thirty of them in Mother's desk drawer. They forgot to remove her name from a few mailing lists and the mailman brought one even the year before last, which she kept reading for days, “Poor little Winkler, how cleverly he portrayed Harpagon; isn't life just awful, even to great actors like him, and there are no exceptions? Terrible. Simply terrible. Don't forget Son, today Winkler, tomorrow you. In this, there are no exceptions.”

Sometimes she would take all the death notices out of her drawer and lay them out on her desktop as if playing solitaire. They were oily from frequent handling, like the cards of fortune-telling Gypsy women, but these notices were far more communicative about the exact time and the circumstances of death and things like with tragic suddenness and after-prolonged illness. For hours, Mother would keep arranging the black-margined notices in chronological order or by the age of the deceased, or she would group them according to religious affiliation, while sipping her mint tea.

.   .   .

On average, Protestants live six fewer years than we do. That is not by chance. These things are not a matter of chance, Son, she said.

You're probably right, Mother, but I must work, I said, and she returned to her room and continued to figure who would live longer.

.   .   .

The previous Sunday I had traveled to the countryside for a reading engagement. I accepted these invitations not so much for the money as for a change of surroundings. I did the shopping and cooked the food for Mother, and then locked the door on her from the outside; even after I turned the key for the second time, I heard her when are you coming back?

Soon, Mother, tomorrow evening the latest, the soup is in the fridge, don't forget to heat it up, and turn off the TV for the night, I said again, this time only to the double-locked door reinforced with a crossbar, and she responded by engaging the security chains, which she did not without reason, from her point of view; just as from her point of view it made sense that she had her own fire extinguisher, a large variety of disinfectants, and a Wertheim safe; from her point of view it made sense that she had me open her mail for weeks after she had seen on TV what was left of a prime minister or a mayor when they opened their own letters.

Nothing but shreds, Son, they showed the shreds around the desks, she said, and hastened to the safety of the toilet, as if entrusting me with opening the envelopes only because she had to pee. And then one night she rapped on my door, stopped at the threshold â she'd never walk into my room when I was at home â and went into her spiel of you want to kill me with this cigarette smoke, and I told her I'd air out the place soon, Mother, but she kept standing in the doorway.

What's bothering you, Mother? I asked.

You know very well what's bothering me. Don't read my letters. This is my life, my own life, which is none of your business, d'you understand? And I said all right, from now on I won't open them, but now please go to bed, it's three o'clock in the morning; and in the last few months I haven't written her any more letters.

.   .   .

I walked to the railway station, barely a thirty-minute leisurely stroll, which I needed. I'd always take a walk before going anywhere; even going to the store I'd first do a round in the Museum Garden or just around the block, while preparing myself for sentences that do not end in the word

mother

. But this is not quite accurate. Not merely for different sentences, I had to prepare for different gestures as well as for a different way of breathing. The first few minutes were always like some kind of no-man's-land, because for fifteen years it was between her when are you coming back and where have-you been that the seasons changed, the Danube overflowed, and a shameful empire fell apart. Everything happened from when are you coming back to where have you been: brokers of the soul established religions, chartered accountants rewrote the Revelation of Saint John, tornadoes were named after female singers, earthquakes after politicians, fifteen Nobel Peace Prizes found their laureates and as many old women managed to escape in a small boat from the last leper colony in the world. Between a single when are you coming back and where have you been three new welfare laws and three hundred satellites began to function; in Asia three languages were declared defunct and in Chile three thousand political prisoners were eliminated with the help of a collapsing mine. Between when are you coming back and where have you been the nearby all-night supermarket went bankrupt, and a cheating tax collector roamed our neighborhood; the former mailman went blind from smuggled vodka made of methyl alcohol, and a burst water main, like a geyser, spewed up all its muck. But it was also between these two questions that our concierge kicked the fetus out of his own daughter's belly, because fourteen-year-old EmÅke said she loved the gym teacher with all her heart and wanted no abortion. Her father

delivered the first kick when my mother asked when are you coming back, and by the time I got home from being with Eszter and lied that I had been to a concert, EmÅke was already through her first operation.