Travels into the Interior of Africa (27 page)

Read Travels into the Interior of Africa Online

Authors: Mungo Park,Anthony Sattin

June 2nd

– We departed from Seesukunda, and passed a number of villages, at none of which was the coffle permitted to stop, although we were all very much fatigued; it was four o’clock in the afternoon before we reached Baraconda, where we rested one day. Departing from Baraconda on the morning of the 4th, we reached in a few hours Medina, the capital of the king of Woolli’s dominions, from whom the reader may recollect I received a hospitable reception in the beginning of December 1795 in my journey eastward.* I immediately enquired concerning the health of my good old benefactor, and learned with great concern that he was dangerously ill. As Karfa would not allow the coffle to stop, I could not present my respects to the king in person; but I sent him word by the officer to whom we paid customs, that his prayers for my safety had not been unavailing. We continued our route until sunset, when we lodged at a small village a little to the westward of Kootakunda, and on the day following arrived at Jindey, where, eighteen months before, I had parted from my friend Dr Laidley, an interval during which I had not beheld the face of a Christian, nor once heard the delightful sound of my native language.

Being now arrived within a short distance of Pisania, from whence my journey originally commenced, and learning that my friend Karfa was not likely to meet with an immediate opportunity of selling his slaves on the Gambia, it occurred to me to suggest to him that he would find it for his interest to leave them at Jindey until a market should offer. Karfa agreed with me in this opinion, and hired, from the chief man of the town, huts for their accommodation, and a piece of land on which to employ them in raising corn and other provisions for their maintenance. With regard to himself, he declared that he would not quit me until my departure from Africa. We set out accordingly, Karfa, myself, and one of the Foulahs belonging to the coffle, early on the morning of the 9th; but although I was now approaching the end of my tedious and toilsome journey, and expected in another day to meet with countrymen and friends, I could not part, for the last time, with my unfortunate

fellow-travellers

, doomed, as I knew most of them to be, to a life of captivity and slavery, in a foreign land, without great emotion. During a wearisome peregrination of more than five hundred British miles, exposed to the burning rays of a tropical sun, these poor slaves, amidst their own infinitely greater sufferings, would commiserate mine; and frequently of their own accord, bring water to quench my thirst, and at night collect branches and leaves to prepare me a bed in the wilderness. We parted with reciprocal expressions of regret and benediction. My good wishes and prayers were all I could bestow upon them, and it afforded me some consolation to be told, that they were sensible I had no more to give.

My anxiety to get forward admitting of no delay on the road, we reached Tendacunda in the evening, and were hospitably received at the house of an aged black female called Seniora Camilla, a person who had resided many years at the English factory, and spoke our language. I was known to her before I had left the Gambia, at the outset of my journey; but my dress and figure were now so different from the usual appearance of a European, that she was very excusable in mistaking me for a Moor. When I told her my name and country, she surveyed me with great astonishment, and seemed unwilling to give credit to the testimony of her senses. She assured me that none of the traders on the Gambia ever expected to see me again; having been informed long ago, that the Moors of Ludamar had murdered me, as they had murdered Major Houghton. I enquired for my two attendants, Johnson and Demba, and learned with great sorrow that neither of them was returned. Karfa, who had never before heard people converse in English, listened to us with great attention. Everything he saw seemed wonderful. The furniture of the house, the chairs, etc, and particularly beds with curtains, were objects of his great admiration; and he asked me a thousand questions concerning the utility and necessity of different articles, to some of which I found it difficult to give satisfactory answers.

On the morning of the 10th, Mr Robert Ainsley, having learnt that I was at Tendacunda, came to meet me, and politely offered me the use of his horse. He informed me that Dr Laidley had removed all his property to a place called Kaye, a little farther down the river, and that he was then gone to Doomasansa with his vessel to purchase rice, but would return in a day or two. He therefore invited me to stay with him at Pisania until the Doctor’s return. I accepted the invitation, and being accompanied by my friend Karfa, reached Pisania about ten o’clock. Mr Ainsley’s schooner was lying at anchor before the place. This was the most surprising object which Karfa had yet seen. He could not easily comprehend the use of the masts, sails, and rigging, nor did he conceive that it was possible, by any sort of contrivance, to make so large a body move forwards by the common force of the wind. The manner of fastening together the different planks which composed the vessel, and filling up the seams so as to exclude the water, was perfectly new to him; and I found that the schooner, with her cable and anchor, kept Karfa in deep meditation the greater part of the day.

About noon, on the 12th, Dr Laidley returned from Doomasansa, and received me with great joy and satisfaction, as one risen from the dead. Finding that the wearing apparel which I had left under his care was not sold nor sent to England, I lost no time in resuming the English dress, and disrobing my chin of its venerable encumbrance. Karfa surveyed me in my British apparel with great delight, but regretted exceedingly that I had taken off my beard, the loss of which, he said, had converted me from a man into a boy. Dr Laidley readily undertook to discharge all the pecuniary engagements I had entered into since my departure from the Gambia, and took my draft upon the Association for the amount. My agreement with Karfa (as I have already related) was to pay him the value of one prime slave, for which I had given him my bill upon Dr Laidley before we departed from Kamalia; for, in case of my death on the road, I was unwilling that my benefactor should be a loser. But this good creature had continued to manifest towards me so much kindness, that I thought I made him but an inadequate recompense, when I told him that he was now to receive double the sum I had originally promised, and Dr Laidley assured him that he was ready to deliver the goods to that amount whenever he thought proper to send for them. Karfa was overpowered by this unexpected token of my gratitude, and still more so when he heard that I intended to send a handsome present to the good old schoolmaster, Fankooma, at Malacotta. He promised to carry up the goods along with his own, and Dr Laidley assured him that he would exert himself in assisting him to dispose of his slaves to the best advantage, the moment a slave vessel should arrive. These and other instances of attention and kindness shown him by Dr Laidley, were not lost upon Karfa. He would often say to me, ‘My journey has indeed been prosperous!’ But, observing the improved state of our manufactures, and our manifest superiority in the arts of civilised life, he would sometimes appear pensive, and exclaim, with an involuntary sigh,

fato fing inta feng

, ‘black men are nothing.’ At other times he would ask me, with great seriousness, what could possibly have induced me, who was no trader, to think of exploring so miserable a country as Africa? He meant by this, to signify that, after what I must have witnessed in my own country, nothing in Africa could, in his opinion, deserve a moment’s attention. I have preserved these little traits of character in this worthy Negro, not only from regard to the man, but also because they appear to me to demonstrate that he possessed a mind

above his

condition;

and to such of my readers as love to contemplate human nature in all its varieties, and to trace its progress from rudeness to refinement, I hope the account I have given of this poor African will not be unacceptable.

No European vessel had arrived at Gambia for many months previous to my return from the interior; and as the rainy season was now setting in, I persuaded Karfa to return to his people at Jindey. He parted with me on the 14th with great tenderness; but as I had little hopes of being able to quit Africa for the remainder of the year, I told him, as the fact was, that I expected to see him again before my departure. In this, however, I was luckily disappointed, and my narrative now hastens to its conclusion, for, on the 15th, the ship Charlestown, an American vessel, commanded by Mr Charles Harris, entered the river. She came for slaves, intending to touch at Goree to fill up, and to proceed from thence to South Carolina. As the European merchants on the Gambia had at this time a great many slaves on hand, they agreed with the captain to purchase the whole of his cargo, consisting chiefly of rum and tobacco, and deliver him slaves to the amount, in the course of two days. This afforded me such an opportunity of returning (though by a circuitous route) to my native country, as I thought was not to be neglected. I therefore immediately engaged my passage in this vessel for America; and having taken leave of Dr Laidley, to whose kindness I was so largely indebted, and my other friends on the river, I embarked at Kaye on the 17th day of June.

Our passage down the river was tedious and fatiguing, and the weather was so hot, moist, and unhealthy, that before our arrival at Goree, four of the seamen, the surgeon, and three of the slaves had died of fevers. At Goree we were detained for want of provisions until the beginning of October.

The number of slaves received on board this vessel, both on the Gambia and at Goree, was one hundred and thirty, of whom about twenty-five had been, I suppose, of free condition in Africa, as most of them being Bushreens, could write a little Arabic. Nine of them had become captives in the religious war between Abdulkader and Damel, mentioned in the latter part of the preceding chapter; two of the others had seen me as I passed through Bondou, and many of them had heard of me in the interior countries. My conversation with them in their native language gave them great comfort; and as the surgeon was dead, I consented to act in a medical capacity in his room for the remainder of the voyage. They had, in truth, need of every consolation in my power to bestow, not that I observed any wanton acts of cruelty practised either by the master or the seamen towards them, but the mode of confining and securing Negroes in the American slave ships (owing chiefly to the weakness of their crews), being abundantly more rigid and severe than in British vessels employed in the same traffic, made these poor creatures to suffer greatly, and a general sickness prevailed amongst them. Besides the three who died on the Gambia, and six or eight while we remained at Goree, eleven perished at sea, and many of the survivors were reduced to a very weak and emaciated condition.

In the midst of these distresses, the vessel, after having been three weeks at sea, became so extremely leaky as to require constant exertion at the pumps. It was found necessary, therefore, to take some of the ablest of the Negro men out of irons, and employ them in this labour, in which they were often worked beyond their strength. This produced a complication of miseries not easily to be described. We were, however, relieved much sooner than I expected, for the leak continuing to gain upon us, notwithstanding our utmost exertions to clear the vessel, the seamen insisted on bearing away for the West Indies, as affording the only chance of saving our lives. Accordingly after some objections on the part of the master, we directed our course for Antigua, and fortunately made that island in about thirty-five days after our departure from Goree. Yet even at this juncture we narrowly escaped destruction, for on approaching the north-west side of the island we struck on the Diamond Rock, and got into St. John’s harbour with great difficulty. The vessel was afterwards condemned as unfit for sea, and the slaves, as I have heard, were ordered to be sold for the benefit of the owners.

At this island I remained ten days, when the Chesterfield Packet, homeward bound from the Leeward Islands, touching at St John’s for the Antigua mail, I took my passage in that vessel. We sailed on the 24th of November, and after a short but tempestuous voyage, arrived at Falmouth on the 22nd of December, from whence I immediately set out for London, having been absent from England two years and seven months.

I

n 1797

, the fledgling British Museum occupied Montagu House, a lordly home surrounded by wooded gardens in what is now central London. Early on Christmas Day that year, James Dickson was alone in the gardens. Dickson, a Scottish seedsman, was so absorbed by his task that he did not hear anyone enter the side gate. So when he looked up and saw a man coming towards him through the gloom, he believed he was seeing the ghost of a man who was supposed to be deep in the heart of Africa. It was his brother-in-law, Mungo Park.

It was through Dickson that Park had met Sir Joseph Banks, a man with a unique position in British society. One of the wealthiest people in the country, and one of the best connected too, Banks had decided early in his life not to become involved directly in politics. Instead he devoted his talent and his considerable means to the pursuit of scientific interests. He had, for instance, paid a small fortune for the privilege of being the botanist to accompany Captain James Cook on his second voyage around the world. In 1771, Banks returned from the South Seas to a hero’s welcome in London – at the time he was as famous as Cook. Seven years later, he was elected president of the country’s leading scientific organisation, the Royal Society. Settled in London, Banks now enjoyed the friendship of King George III, who gave him care of the royal gardens at Kew. Banks also became adviser on scientific matters to His Majesty’s government, a

one-man

Department of Science. He was also an active member of London’s intellectual and social life, a frequenter of the dinners of a string of clubs and societies including the Royal Society Club, the Society of Dilettanti, the Society of Arts and a little-known group called the Saturday’s Club.

Nothing is known of the Saturday’s Club until nine of its dozen members met for dinner at the St Alban’s Tavern on 9 June 1788 – not a Saturday, note, but a Monday – and created the Association for the Promotion of the Discovery of the Interior Parts of Africa, the African Association for short. Banks and his friends Lord Rawdon (later Marquis of Hastings and Governor-General of India), the anti-slavery MP Henry Beaufoy and the Scottish improver Sir John Sinclair, founder of the Board of Agriculture, were among the members. The resolution they voted on that day stressed the geographical nature of their project:

That as no species of information is more ardently desired, or more generally useful, than that which improves the science of Geography; and as the vast continent of Africa, notwithstanding the efforts of the ancients, and the wishes of the moderns, is still in a great measure unexplored, the members of this Club do form themselves into an Association for promoting the discovery of the inland parts of that quarter of the world.

Which part of ‘that quarter of the world’ would they investigate first? The choice soon became obvious: since antiquity, Africa was known to have two extraordinary rivers, the Nile and the Niger. On some maps these two rivers were shown to be connected, the Niger running across the continent and joining the Nile, which then ran due north to the Mediterranean. Somewhere along the Niger, they knew, there was a great trading city called Timbuktu where gold was in such abundance that even the slaves were adorned with it.

Within two weeks of the Saturday’s Club dinner, Banks and his friends had agreed upon a plan to bisect the northern half of the continent in search of the Niger: they would send one explorer south from Tripoli in Libya and another west from the Red Sea coast of Sudan. In so doing, they were to usher in the great age of overland exploration.

Within two weeks, they had also engaged two travellers. John Ledyard was an American who had sailed on Cook’s last voyage and was intent on becoming the first person to circumnavigate the world by land. He was sent to make the east-west crossing ‘as nearly as possible in the direction of the Niger’, as it was put in his instructions, ‘with which River, and with the Towns and Countries on its borders, he shall endeavour to make himself acquainted’. Unfortunately he died in Cairo before he could even begin his journey. The other traveller was Simon Lucas, King George III’s Oriental Interpreter, who volunteered to sail to Tripoli. In one way, Lucas seemed an ideal candidate for the job. As a youth, he had been captured by pirates and sold as a slave to the emperor of Morocco, so he knew the language and mentality of the region. But he was no adventurer and lacked the temperament to travel into Africa; before he had even left the Mediterranean coast for the interior, he decided to return to London.

While their first travellers were out in the field, Banks and his colleagues on the committee of the African Association were busy collecting information on the interior from other sources, including dispatches from British consuls along the North African coast. They also tried to make contact with Moorish traders passing through London. From two of these men – Ben Ali and Shabeni – they learned a great deal about travelling conditions in the interior. Ben Ali, who had already been to Timbuktu, went further than mere words and offered to take one of the Association’s travellers into the heart of Africa. But his terms were too steep and his behaviour too bizarre: before an agreement could be reached, Ben Ali had disappeared.

The Association’s plans were now changed to reflect this

newly-acquired

knowledge: the Committee decided to approach the interior from the Gambia River. This time, they chose an Irishman, Major Daniel Houghton. Houghton had travelled in Morocco and spent several years serving at the fort on Ile de Gorée, just off the Senegalese coast (near present-day Dakar), so was well-seasoned. In October 1790, he sailed for the Gambia River, made contact with Dr Laidley, a British slave trader operating along the river, enjoyed the hospitality of the King of Wuli – who assured him he could walk to Timbuktu ‘with only a stick in my hand’ – and then set off for the interior. On 1 September 1791, he sent Laidley the following note: ‘Major Houghton’s compliments to Dr Laidley, is in good health on his way to Tombuctoo, robbed of all his goods by Fenda Bucar’s son.’ After that, silence. It was not until the African Association’s annual meeting of 1794, held at the Thatched House Tavern in Pall Mall, that the secretary, Henry Beaufoy, announced the Committee’s belief that Houghton had been murdered. Beaufoy also announced that an application had been ‘received from Mr Mungo Park to engage in the service of the Association as a Geographical Missionary’.

Park had enjoyed Sir Joseph Banks’ patronage for some years before he offered his services to the Association. Through Banks, Park had been employed as assistant surgeon on an East India Company ship sailing for Bencoolen in Sumatra and had had his paper

Eight small fishes from the coast of Sumatra

read before the fledgling Linnaean Society (another of Banks’ endeavours). In May 1794 Park had written to his brother that ‘I have … got Sir Joseph’s word that if I wish to travel he will apply to the African Association.’ As we know, he did wish to travel, Banks made the arrangements and Park had the pleasure of seeing the Niger, as he described it, ‘glittering to the morning sun, as broad as the Thames at Westminster.’

Park returned to Britain in triumph. He was the first Association traveller to reach the interior and live to tell the tale and, what’s more, he had settled one of the puzzles of African geography. He might not know where the Niger terminated, but he could confirm that it flowed to the east.

Banks lost no time in spreading the news of Park’s and the

Association’s

success. The timing was fortuitous – the war against the French was going badly, Napoleon had defeated the Austrians, the Royal Navy was close to mutiny over bad conditions and worse leadership. Things were so bad that the French had even managed to make a landing in Wales the previous year. Park’s success was a welcome diversion and the press were happy to play it up: several newspapers ran stories in the weeks after his return.

The Times

went so far as to claim that Park had made contact with a great city, twice the size of London, whose people were keen to trade with Britain.

London’s beau monde was no less welcoming to the celebrity traveller. Banks and Earl Spencer, a member of the Association and brother of the notorious socialite Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, guaranteed Park’s entry into society, and for a while the twenty-

six-year

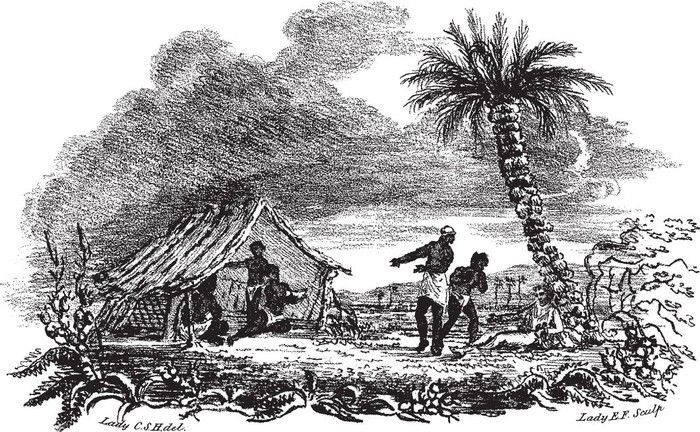

-old Scottish crofter’s son found himself the centre of attention in London’s grand houses. Such was his reputation that the Duchess of Devonshire went as far as to glorify events of the night following his arrival on the Niger in a song, which was put to music by the Italian composer G. G. Ferrari and illustrated with an engraving by the duchess’s companion (and successor) Lady Elizabeth Foster:

Song from Mr Park’s TravelsThe loud wind roar’d,

the rain fell fast,

the white man yielded to the blast:

he sat him down beneath our tree,

for weary, sad and faint was he,

and ah! no wife of mother’s care,

for him the milk or corn prepare;

for him the milk or corn prepare …

When Sir Joseph Banks had come home from his voyage round the world he was only too happy to perform in London’s salons and, no doubt, to keep his male friends entertained over the port with racier stories of his sexual exploits. But Park did not have the temperament for this sort of society.

He had grown up on the Scottish Borders – dour, demanding country – and had then trained as a doctor in Edinburgh. He had first travelled to London at the invitation of his brother-in-law Dickson, who had then brought him to the attention of Sir Joseph Banks. Banks had soon recognised Park’s strength, resourcefulness, intelligence and other qualities – Henry Beaufoy, the Association’s Secretary, called him ‘a young man of no mean talents’. To have survived the many social occasions held at Banks’ Soho Square house, Park must have had the necessary social accomplishments. But on his return from Africa, he soon began to tire of his celebrity. The backlash was inevitable. Where the Duchess of Devonshire had lavished attention on him, her friend Lady Holland now described him as having ‘neither fancy or genius, and if he does fib it is dully.’

The African Association was due to hold its annual meeting of subscribers in May, as usual, and Banks wanted an account of Park’s travels to be ready by then, along with a new map of the area. The map was to be drawn by Major James Rennell, a former East India Company Surveyor-General and now the African Association’s honorary

geographer

. Rennell had a daunting task, for although Park had been sent out with some £65 worth of scientific equipment, including a pocket sextant, a magnetic compass and a thermometer from the master-maker Edward Troughton, he was soon robbed of everything but the compass. From then on, his observations became less specific, less scientific. On several occasions he almost lost whatever notes he had been able to make, which he carried tucked inside his hat. Just before reaching safety on his way out of the interior, stripped of what little he possessed, he had had his hat returned to him presumably because his assailants believed the papers were some sort of magic juju.

The task of helping Park write up his notes fell to the Association’s new secretary, Bryan Edwards. This was to prove a controversial choice. There was no doubting Edwards’ literary talents – his History of the British West Indies was highly praised when it appeared in 1794 and earned him a Fellowship at the Royal Society. By the time of Park’s return, Edwards was an MP and the owner of a bank in Southampton. But he was also the proprietor of large Jamaican estates that relied on slave labour. New laws had made it illegal to hold people in slavery within Britain in the late 1780s, but there was no legislation against slavery or the slave trade elsewhere in the world. There was, however, a growing and increasingly vocal opposition to the trade in Britain (legislation against the slave trade was finally passed by the British parliament in 1807). Members of the African Association were at the forefront of the campaign against the trade, most obviously the leading anti-slavery campaigner William Wilberforce. But it was Bryan Edwards, the Association’s pro-slavery Secretary, who was given the task of encouraging Park in his literary endeavours and of preparing a brief account of his travels for the members. Meanwhile Banks was making other plans.

Banks’ interests literally reached around the world. Among his many activities in 1788, for instance, he had founded the African Association, overseen the first Australian settlements and campaigned for tea plants to be shipped from China to India. Lord Hobart, the Foreign Secretary, was not exaggerating when he wrote to Banks that ‘Wide as the world is, traces of you are to be found in every corner of it.’ In May 1798, Park still had the full account of his travels to write, but Banks was already planning his protégé’s next voyage, the exploration of the interior of Australia. He had already written to the Home Office suggesting they employ Park for that purpose.