Treblinka Survivor: The Life and Death of Hershl Sperling (19 page)

Read Treblinka Survivor: The Life and Death of Hershl Sperling Online

Authors: Mark S. Smith

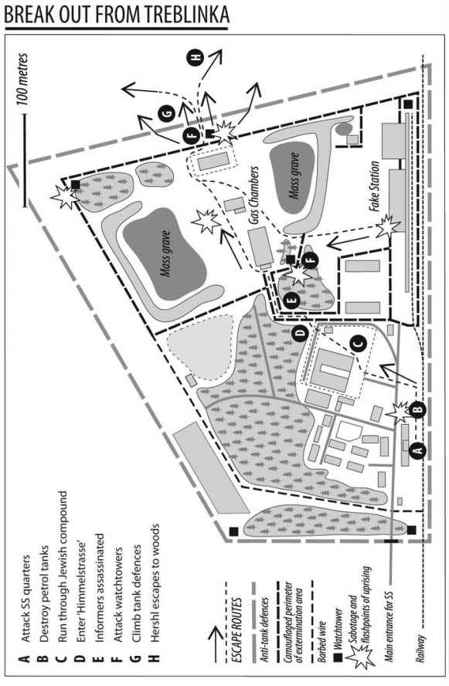

Now the potato workers, armed with grenades and rifles, moved toward their predetermined target – the SS headquarters, which were to be set ablaze. This was a crucial part of Galewski’s original plan. Several grenades were thrown, which exploded, but caused no casualties. Hershl writes: ‘A hand grenade is thrown at

Oberscharführer

Franz.’

This is a curious error, which contradicts his own earlier statement that Franz and 40 others had gone swimming – unless he is referring to Franz Stangl, the camp commander, although the rank would then be incorrect. He might also be referring to Franz Suchomel, who was indeed an

Oberscharführer

, or sergeant.

Stangl, during his interview with Sereny, recalled the advance of the potato workers.

Looking out of my window, I could see some Jews on the other side of the inner fence. They must have jumped down from the roof of the SS billets and they were shooting. I … took my pistol and ran out. By that time the guards had begun to shoot, but there were already fires all over the camp.

The largest blaze of the Treblinka uprising, however, was yet to be ignited. All the accounts of survivor-witnesses and the concurring SS accounts tell of this giant explosion. Lubraniecki and Lichtblau, both with grenades and rifles in their hands, had been ordered to take out the camp garage and the gasoline pump at the far eastern end of Kurt Seidel Strasse. Here, they discovered an armed vehicle with a mounted machine-gun parked beside the pump. Lichtblau drove and Lubraniecki fired at the Ukrainians in the watchtower and on the ground. The vehicle’s loud rumble and the wrenching sound of its gun turret turning and the rapid fire of its bullets rose above the chaos.

At some point, they turned back toward the gasoline pump and were hit by gunfire. Nonetheless, they managed to launch an assault on the pump and gasoline store, which went up in a thunderous explosion, shaking the entire camp. A pillar of fire burst into the sky. The flames spread to the SS barracks and the bakery, engulfing everything. The heat was infernal, as though a lid had been lifted from hell itself. Lubraniecki and Lichtblau died in that moment. Hershl writes:

All the telephone lines are cut; the vehicles are disabled, so that they can’t be driven; whatever petrol we can obtain is poured out and lit; the death-camp Treblinka begins to burn. Pillars of fire ascend to the sky. The SS shoot back chaotically into the fire.

Eyewitness Samuel Willenberg, in his

Revolt in Treblinka,

writes:

The Germans’ huts burned in a devil’s dance. The dry pine branches we had inserted in the fence burned as well, giving the fence the appearance of a giant dragon with tails of fire. Treblinka had become one massive blaze.

Franciszek Zabecki, who was about four kilometres away, recalls:

Observing from the railway station in Treblinka on a hot Monday 2 August 1943, at 15:45 we saw huge wreaths of smoke mixed with tongues of fire in the skies over the death camp. It was different smoke from that which we saw every day, that smoke of martyrdom. At the same time, the sound of shots and detonations grew nearer. We began to realise a revolt had broken out in the camp, that the camp had been set on fire by the Jews and that fighting was going on there.

The insurgents now fired furiously at the Germans and Ukrainians, who attacked from all sides and were shooting at the Jews through the flames. Several Ukrainians were wounded and their weapons were taken from them. At some point, an exchange of gunfire between prisoners and SS men brought down Seidel, one of only four SS men who were to die that day.

Just after the first shots and the explosions of grenades, Zialo Bloch signalled the beginning of the rebellion in the death camp. He and the others in the water-carrying team attacked their two Ukrainian guards with an axe and killed them, taking their rifles. They then threw the guards into the well. Bloch sent one of the carriers running to the barracks to call out the secret words: ‘Revolution in Berlin’.

At the same moment, near the watchtower at the far corner of the Totenlager, survivor Berek Rozjman played his part:

I was assigned to get rid of one of the Ukrainian guards in the watchtower near where I worked. The man on duty in the watchtower that day was called Mira. He was sitting in the tower dressed only in his shorts getting the sun. When he heard the first shots from the lower camp and realised there was trouble, he jumped down in his shorts. I ran up to him and said, ‘Mira, the Russians are coming.’ I took his gun away from him and he didn’t move to stop me. ‘You run,’ I said, ‘but I must have your gun.’ He ran.

The prisoners near the Totenlager barracks, armed with pitchforks and shovels, charged out of the barracks and broke through the compound gate, where they killed another Ukrainian guard and took possession of his weapon. Other prisoners broke into the guard room and removed more weapons. The prisoners at the cremation site attacked and killed their Ukrainian guard also. Bloch and others were seen firing at the watchtowers.

Within a matter of minutes, the Jews had taken complete control of the death camp area. The gas chambers were set alight, as were several wooden buildings which housed the Totenlager women’s barracks, the kitchen, the kapos’ quarters and men’s barracks. A desperate bid to escape ensued. Some of the prisoners headed for the southern fence of the camp, near the burning barracks, and cut through the barbed wire with axes. Elsewhere along the perimeter fence, prisoners threw blankets over the wire, and boards and boxes up against it, and began to flee. On their way toward the second fence, they had to cross the anti-tank rolls. Many were caught in the barbed wire and shot by Ukrainians from the towers. Witnesses have recalled how Bloch and Adesh ran from one group of prisoners to another among the flames, rousing everyone to fight and escape.

In the lower camp, some 300 prisoners were trapped in the ghetto when the flames spread from the bakery on Kurt Seidel Strasse to the roof of the ghetto kitchen and to the prisoners’ barracks, blocking the gate and the prisoners’ exit. Hershl and Rajzman, as well as several armed members of the Underground, were among this panicked group. As the flames spread over the wooden huts, the Jews surged into the courtyard. A score was settled amid the chaos. Witnesses have recalled how prisoners murdered Kuba, the notorious informant, near the ghetto workshops, as the flames climbed high into the sweltering afternoon.

A large crowd now gathered at the carpenters’ and locksmith’s workshops, whose windows backed on to the eastern edge of the ghetto fence. The prisoners used axes and hacksaws to break the iron bars on the window and now grappled through the opening. The first ones through the windows used pliers and axes to cut through the fence. They all fled toward the Totenlager. The fence of the

Himmelstrasse

was broken down and en masse they flooded into the extermination area. This terrible route, through which had passed so many innocents, now served as an escape channel. Now another score was settled. Paulinka, or Perla, the women’s kapo and a notorious informant, had betrayed at least six Jews to Küttner and was herself feared for her cruelty. The SS later found her with her head shattered on the

Himmelstrasse

.

Meanwhile, the battle raged on between the insurgents and the guards. The Underground’s idea – heroic from the start – was to pin down the SS and Ukrainian guards and allow the prisoners to escape. They were determined now – in spite of their failure to take control of the lower camp – that at least some of the prisoners would escape. Rajzman wrote: ‘They dreamed of setting fire to the whole camp and exterminating at least the cruellest engines at the price of their own lives.’

In the general confusion, the camp’s telephone line to the outside world was not cut. Nor did they manage to completely destroy the gas chambers, the only structures in the camp made of brick, and they did not eliminate the threat from all the watchtowers. The insurgents continued their assault on the Ukrainians in the watchtowers and at the SS at various positions, but their ammunition and grenades began to run out. Prisoner Rudolph Masarek, a 29-year-old from Prague, who had accompanied his wife to Theresienstadt and on to Treblinka, was seen lying on top of a roof, taking shots at the SS. He was heard calling: ‘This is for my wife and my child who never saw the world!’ His pregnant wife had been taken to the gas chambers on arrival some ten months earlier, but he was left alive to work. Those prisoners who were armed were last to make for the fences. Most were hit and died where they fell. Masarek did not survive the revolt.

Eyewitness Glazar, in his

Trap Within a Green Fence

writes: ‘He died, deliberately, for us.’ Bloch and Adesh, and many of the other armed rebels, continued firing to cover the escapees. However, they too ran out of bullets and fell where they were shot.

Those running from the lower camp now joined the prisoners fleeing in the extermination area. Others fled through the Sorting Square southward, some with pitchforks and shovels in their hands. Bullets whizzed around them and over their heads. Hershl writes: ‘The thousand or so Jews in the camp break through the fence … A frenzied activity begins.’

The prisoners scrambled wildly over the fence, many climbing over the bodies of their fellow Jews who had already fallen, now so deep that a bridge had been made over the perimeter fence complex. Dozens of prisoners jumped through the flames and into gaps in the fence. Many of them got caught up in the barbed entanglements of anti-tank rolls between the two fences and were shot by the Ukrainians. Others were killed on the second fence. At some point in the chaos, Hershl and Rajzman were separated. Miraculously, neither was hit. Survivor Rachel Auerbach wrote that she saw Galewski killing himself with poison after being surrounded, still covering the escapees by drawing the guards’ fire. Hershl writes: ‘On the other side of the fence a path leads into the woods. Heavy fire from the Ukrainians accompanies the escapees. Some are hit, but the great majority reach the woods in safety.’

By 6.00pm, about two hours after the uprising began, 400 of around 800 prisoners had been killed in the fighting, and almost 300 were killed trying to escape into the nearby forest. Around 100 got away. A few prisoners, those who were too weak or fearful, stayed behind in the camp.

SS guard Suchomel, in an interview years later, recalled:

A few days before the revolt, I advised Masarek and Glazar to break out, but I said they should do it in small groups. And they said they couldn’t do that, because if they did there would be terrible reprisals. That’s really something if you come to think of it. And they say the Jews aren’t courageous. I tell you I got to know the most extraordinary Jews.

Now the prisoners fled for their lives across the fields toward the woods. Hershl was one of a group of four who found themselves together. The machine-gun fire from the guard towers was relentless. Bloodied bodies fell all around them. Hershl writes: ‘A mad pursuit begins. The Jews divide themselves into very small groups. I am with three other people. Now there is just one command: “Forward, forward!”’

Behind them, Treblinka burned.

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

One night at my home in Scotland I awoke breathless from a terrible dream. I was in an enormous, muddy pit filled to the brim with corpses. They were mangled and twisted in all manner of unnatural positions, and they lay piled upon one another for as far as I could see in every direction. Eyes and mouths were frozen wide in terror. I was desperate to free myself but the bodies were extraordinarily heavy and I could not extricate myself. I felt trapped and started to panic, struggling desperately to free myself. Suddenly, a hand touched my shoulder and I awoke. It was my wife’s hand; I had been making noises in my sleep and woken her.

‘You were whimpering,’ she said. ‘You couldn’t seem to catch your breath. Are you okay?’

‘Shit,’ I said, wiping the sweat from my face and neck. ‘I’m going to get up for a while. I don’t think I can get back to sleep right now.’

I shuffled to the bathroom and then went to check if my children were still breathing. It had been one of those dreams. I stood for a long time watching them. I realised that Hershl was just a couple of years older than my daughter during his time in Treblinka. What would become of my child, if her mother, father and younger brother were suddenly ripped away and murdered? It was unthinkable, and I hesitated to scribble these things into my notebook later that night, as I sat at the kitchen table with a large Scotch beside me. There are children like this everywhere today, I thought – in places like Darfur, Rwanda, the Balkans and Iraq – and there have been children like this through the ages. What would become of my little girl if she were beaten and bullied to work in Treblinka with the smell of death in her nostrils and the procession of the doomed constantly before her eyes? I could not bear the thoughts any longer, but then I realised that Hershl could not bear them either.

I began to see the child he had been in the late afternoon of 2 August 1943, running from the burning death camp with a group of three other Jews, their backs against the dipping sun. They ran toward the east across a meadow in a frenzy of elation and then plunged into the darkness of the woods. Hershl carried a small sack containing diamonds and gold US dollars. Other groups of fugitives, some with clubs and axes in their hands, ran beside and in front of them. Fear and excitement drove them deeper into the forest’s depths. The pace was exhausting. They leapt over bushes and through dense thickets. They waded waist-deep through ponds and stumbled through water-logged marshland and swamps. They must get as far away from Treblinka as possible.

The next day, I turned again to Hershl’s pale green book. As elsewhere in his account, the description of the desperate escape into the forest, although eventful and rich in detail, omitted those things that had traumatised him the most. I called Sam in the hope that Hershl might have uttered some clue and that he might remember it. Sam paused before answering my question. I sensed this was a difficult subject, because it required him to remember his father’s suffering yet again. Finally, he said:

‘Something terrible happened in the forest.’

‘I knew it,’ I said. ‘I’m beginning to sense in your father’s writing when he purposefully leaves things out. Do you know what it was that happened there?’

‘There were some things my father could speak about, but he could not speak about the forest. I remember the horror on his face when he tried. That same look of horror – and it was real terror – came to him when he tried to speak about the pits and the bodies at Treblinka. He also had that same look whenever Mengele was mentioned.’

‘There are those gaps again,’ I said.

He thought for a long moment. ‘My father mentioned the forest only once that I can remember.’

‘Maybe if you can think about what triggered it, that might help,’ I suggested.

‘I remember when I was living on a kibbutz in Israel and my father came to visit for a few weeks,’ Sam said. ‘It was Yom Ha’atzmaut, Israeli Independence Day, and he wanted to stay and be part of that. I also remember he was speaking Hebrew, and I was surprised at how well he could speak it. I was a little embarrassed actually, because the way he spoke was with this funny Yiddish accent, the same way all the old people on the kibbutz used to speak.’

‘We know he had this gift for languages. It kept him alive.’

‘I have a cousin in Israel, who was then about six or seven. We were in Tel Aviv and my father was taking her out to buy her things, and at one point I think she started to remind him of his sister who had died in Treblinka.’

‘So what did he do?’

‘Well, he became very upset. I guess that brought things back, because afterwards, that night, he started remembering and speaking about things. It was then he mentioned the forest, and he had that look of horror on his face.’

‘What happened in the forest?’

He took a deep breath. ‘I need to think some more about this.’

‘Sam, I think I might have found out something about how he managed to avoid getting captured in the forest.’

‘Tell me.’

‘Well, it’s to do with Samuel Rajzman,’ I said.

‘Go on.’

‘Rajzman came from the village of Wegrow,’ I told him. ‘I don’t know why I hadn’t done it before, but I decided to look up Wegrow on a map of Poland. I discovered, to my surprise, it was less than twenty miles from Treblinka. That means he probably knew the area extremely well, and I suspect he passed that information on to Hershl. It’s speculation, of course, but it would make sense.’

‘We can be absolutely certain that wherever he went in those woods, he was guided by instructions from Rajzman,’ Sam said. ‘There was something about getting to neutral Switzerland, where they intended to meet up and wait for the end of the war.’

‘That seems a long way to go, although the choices of where they could safely wait out the war were limited. They would have to get through, let me see …’ I quickly pulled up an internet map of Europe. ‘Possibly four countries, all of them under Nazi sway, and one of them would probably be Germany itself – unless they planned to go through Austria, which was just as dangerous as Germany in those days. The truth is that there weren’t many places they could go. But then again, I suppose if Rajzman gave him this kind of information, he would try to use it.’

‘My father said again and again how Rajzman had saved his life. He was almost like a deity to him. Look, my father was a crazy character who argued with everyone, but he never argued with Rajzman. I think they had a calming effect on each other. I know Rajzman lost his wife and child in Treblinka. My father also lost his family. They were a surrogate father and son who found each other.’

‘I suspect that just after the breakout, while almost everyone else headed north and east towards Belarus and the front, Hershl headed south, in the direction of Wegrow,’ I suggested. ‘Rajzman also seems to have taken this route to the south, and he managed to hide in the forest for much of the rest of the war – although, to my knowledge, he didn’t make it to Switzerland.’

* * *

The escapees’ chances of success that day were impeded by the Küttner incident, which triggered the premature start of the uprising. This provided the SS with more daylight to hunt down the fugitives. However, their flight, as it was, was at the same time aided by two significant factors. The first was the fact that Franz Stangl, the camp commandant, had been entertaining a visitor in his quarters and they had been drinking heavily since before noon. Former Treblinka guard Franz Suchomel said:

By the time the revolt started in the afternoon, Stangl and his friend were both drunk as lords, and didn’t know which end was up. I remember seeing him stand there, just stand and look at the burning buildings.

This delayed the start of the pursuit. Although the Treblinka telephone lines were still open, Stangl did not alert the authorities in Malkinia until after the camp’s gasoline store had exploded. They also benefited from the fact that so many guards were swimming and sunning themselves at the Bug River that day. Stangl’s adjunct, Kurt Franz, contrary to what has been claimed, was not at the Bug River, at least according to Suchomel: ‘Franz was not in Treblinka that day – that was true enough – but neither was he swimming, though perhaps Stangl thought he was. In fact, he was with his tart in Ostrow.’

After Stangl raised the alarm, all garrisons from Malkinia to Siedlce were mobilised. The Malkinia fire department was also contacted to help quell the flames that were devouring the camp. Indeed, almost all the Germans in Malkinia rushed to the aid of the Treblinka authorities – the gendarmerie, the Gestapo and the railroad guards. They arrived with rifles and pistols, in cars and on a special train. A force of hundreds of men took up the pursuit of the Jews. Ukrainians combed the fields and woods on horseback with tracker dogs. The Polish police were also called in to assist the operation.

Before long, the woods echoed with the sound of galloping horses, barking dogs, gunfire and screaming. Most of the Jews continued east and north, where, if they made it that far, they would eventually have to cross the Bug River. The idea was to keep moving until they reached the front line, where they could cross into Russian territory. Minsk, the capital of Belarus had been retaken on 3 July. Ten days later, the Red Army reached the pre-war Polish border. The Belarusian forests also crawled with partisans and underground resistance fighters. However, few made it that far; most of those who went north and east were caught and murdered within the first 24 hours.

Hershl and his group went south and then west, most likely guided by instructions from Rajzman. They ran for perhaps three hours without stopping. By sundown, all the roads in the area were blocked, and dozens of houses, barns, buildings and rail cars were searched. In railway stations and villages, posters were nailed up alerting the local population to the escape of ‘fifty Jewish bandits’. Poles were warned not to hide them, because it was said they carried typhus. The posters also noted the Jews could be spotted easily by their shaved heads. A number of Poles joined the hunt; a few helped Jews with directions. Fewer still hid them. There were also cases of Poles who hid Jews then denounced them. Still other Poles joined posses. However, most did nothing and remained in their homes for fear of German violence.

Night fell. In the darkness of the forest, Hershl’s group stopped for the first time.

‘We manage to get twelve kilometres away from Treblinka.’

It was high summer and the forest buzzed with insects, which landed on their sweat-dripping faces and sucked their blood. The sweat on their bodies cooled in the night air and they trembled. Hershl was sixteen and the ashes of his mother, father and Frumet, whose beautiful red hair he knew had been shorn in those terrifying moments before her death, were behind him. The distant sound of barking dogs now began to cut through the darkness. Then came the sound of shouting – German from one direction and Ukrainian from another.

Sam called back the following day. ‘I’ve been thinking about the forest, and I’ve remembered some things,’ he said.

‘Okay,’ I said, flicking open my notebook.

‘My father told me once that he had spent a long time hiding in a tree. He told me a lot of crazy things, which at the time I thought were just plain crazy. But that night in Israel, he was saying something about another prisoner that was on the ground that he could see while he was hiding in this tree. I don’t know whether this prisoner was one of the people my father escaped with or whether he was another prisoner who had come into the forest. He was wounded in some way, and he knew my father was in the tree because he was begging him to come down and kill him before the Germans arrived. I got the impression this went on for a long time, this begging and pleading. I don’t know whether my father couldn’t kill him or if he was just too frightened to come down from the tree.’

‘That would have been utterly terrifying,’ I said.

‘It was something that haunted him,’ Sam said. ‘There was a memory of watching this man die slowly, right in front of him. And there was the guilt either about not helping him or not killing him. I don’t whether he was eventually killed by the SS or whether he died right there, below my father.’

While the posters mentioned only 50 fugitives, around 300 prisoners made it into the forest. However, less than half of them survived until the following morning. Most were captured and murdered in the forest by the pursuing forces, and local peasants murdered others for reward money. Yet the remaining 100 or so escapees, Hershl amongst them, managed to avoid the extensive dragnet.

During that first night, Hershl climbed down from the tree and rejoined the rest of the group. Perhaps they too were up trees. They continued their desperate march through the night under the protective cover of the dense woods. They were covered with dried blood, scratches and mud. The next day they hid and slept, and at nightfall continued their flight.

At night fear drives us on. By day we do not dare to move for fear of being seen. We hide in inaccessible places. We wonder whether we still have any chance of staying alive, or whether it would not be easier to take our own lives. One of us talks of hanging himself. But in the end the will to live is stronger.

By the third night, the ache in their bellies became unbearable.

We are beginning to be tormented by hunger. Being the best Polish speaker, I creep into the nearby village to get something to eat.

By now, the group must have been somewhere near Rajzman’s village of Wegrow.

Slowly, hesitatingly, indecisively, with a pounding heart, I come out of the wood and approach a peasant house standing on its own. It is about thirty kilometres from Treblinka. Raising my eyes to heaven and praying, I step onto the threshold of the house.