Trials of Passion (35 page)

Authors: Lisa Appignanesi

In the early 1900s New York's Madison Square Garden was located at Madison and 26th Street at the edge of the neighbourhood nicknamed the Tenderloin'. This was the raucous entertainment centre of America's Gilded Age. Known to Manhattan's anti-vice brigades as âSatan's Circus' or âGomorrah', the area teemed with brothels and casinos, theatres and music halls, bars, hotels and clubs. Here poverty jostled against wealth, and crime was rife. So too was corruption. Protection rackets thrived and the police fattened themselves on bribes. Indeed the area had got its name from âClubber' Williams's comment on arriving at his new police precinct in 1876: he had thus far lived on chuck steak, he said, but now he'd be having a bit of tenderloin.

There wasn't much of that for the working class of the area, and as the century turned, organized strikes and protest grew â amongst newsboys, women in the garment industry and ârapid transit' workers, to name just a few. Sometimes public protest spilled over into the Square after which the Garden was named. But with the years, that area grew increasingly affluent: Willa Cather in her

My Mortal Enemy

would evoke it as âan open-air drawing room' â one where women's virtue was ever an issue.

Built in 1890 to replace a prior sporting and entertainment complex, the new and gracious âGarden' was in the latest European Beaux Arts style. It was topped by an elegant cupola modelled on the minaret-like bell tower of the Cathedral of Seville. The style expressed the aspirations of the city's elite, those âfour hundred', as Mrs William Backhouse Astor's mythical number had it, who could receive an invitation to her Patriarch Balls on the strength of being the crème de la crème of society, not just money-grubbing, newly rich arrivistes. Luckily, ânew' was a fluid term.

At thirty-two storeys, the Garden was Manhattan's second-tallest building, and it came in at a cost of three million dollars to the financial group that backed it â one that included America's leading financiers: J. P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, W. W. Astor amongst them. The cost of such a building project today would probably be between $365 and $596 million. But this was America's Gilded Age: for the rich of that era before income tax, money accumulated unstoppably. The Garden's main auditorium seated eight thousand and had floor space for thousands more. It had a twelve-hundred-seat theatre, a larger concert hall, the city's biggest restaurant, and a roof garden-cabaret where champagne flowed and chorus girls sang.

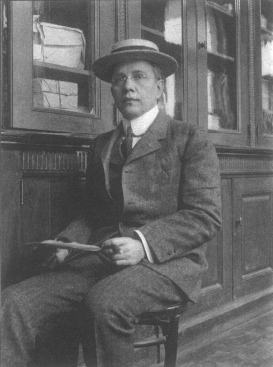

The building's architect was the time's most eminent and the most beloved of its aristocracy of wealth. The name Stanford White (1853â1906) was a byword for taste and elegance. His firm McKim, Mead & White had designed Tiffany's, the New York Herald Building modelled on the Doge's Palace in Venice, the graceful Washington Square Memorial Arch and a host of plush restaurants, public buildings, churches and amenities, not to mention opulent mansions both on Fifth Avenue and in the country. Unlike other architects of his day, White also designed interiors and sumptuous parties, such as might transform a New York restaurant into Versailles's Grand Trianon and feature lavish spectacles of music and ballet. Of course, he attended these as well.

Many of White's gracious buildings have now vanished, but two country establishments have been restored and give a flavour of the

âAmerican Renaissance' style in architecture which he helped to shape. Astor Courts, on John Jacob Astor TV's 2800-acre estate, Ferncliff, combined classical colonial with Beaux Arts to create a luxurious summer residence. It included the first indoor pool, as well as a bowling alley and shooting range. For the Vanderbilts, there was a columned limestone mansion on the banks of the Hudson River, now a historic building in which Stanford White's interiors remain largely intact.

Tall, rugged, mustachioed, his reddish hair brush-cut, his suits impeccable, White was a gentleman and an aesthete who knew Shakespeare by rote from his scholar father and was familiar with the museums of the world. He was charming and cultivated. He was also something of a voluptuary. A regular at the extravagant festivities the great hostesses of the day provided, White was a lover of the best cuisine and a collector of the most beautiful women. The cities of Europe were his regular haunts â shopping grounds for style as well as for objects to be shipped home to embellish the houses of rich clients and his own. He had a luxurious multi-gabled estate in Box Hill on Long Island, a three-hour journey away, a well connected wife, Betty Smith, and a much loved son. He also had a town house on East Twenty-first Street, a bachelor flat for private entertainment and an apartment for his own use at the very top of the Madison Square Garden.

A lift brought you up the eighty-foot tower, where White's rooms were built in horseshoe shape around the shaft. Blue and emerald- green Tiffany dragonfly sconces lit the space, their light reflected in a wall-sized gilt mirror. A moss-green tufted velvet sofa, an ebony grand piano on which a bronze Bacchante sculpture by a famous artist was poised, a rosewood table, exotic flowers, and bird-of-paradise plants brought from Florida ... All this is what met the large, waif-like eyes of fetching sixteen-year-old Evelyn Nesbit when she first entered White's sumptuous apartment in the autumn of 1901. A lauded recent addition to the chorus of the hit show

Floradora

, Evelyn was already a much sought-after artist's and photographer's model. She had been dubbed âthe most beautiful specimen of the skylight world'.

The further climb up a narrow wrought-iron spiral staircase to

reach the turreted top of the Garden's tower would have been easy for the nimble Evelyn. From here, you could have a close-up view of another nubile beauty â a shining, virginal Diana, who spun with the wind, her bow and arrow ever at the ready. She was the product of the time's most famous artist, Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The Puritan guardians of New York's virtue, led by the redoubtable and vociferous anti-vice campaigner Anthony Comstock, had protested against the statue's brazen glittering nudity. In provocative response, White and Saint-Gaudens had decked Diana in gauzy drapery. But her robes blew away within weeks, and Diana's champions proceeded to illuminate her so that she became brilliantly visible, even at night. Back when Diana had first arrived atop the tower, a

Mercury

reporter had written, The Square is now thronged with clubmen armed with field glasses ... No such figure has ever before been publicly exhibited in the United States.'

White, who was a connoisseur of the female form as well as of architectural structures, knew that this first Diana, who weighed in at 820kg of copper gilt and measured 5.5 metres in height, was too heavy to spin on the globe pedestal provided for her, and in 1893 she was replaced by a smaller, hollow version of herself â the one young Evelyn Nesbit gazed on during her visits to White. Whatever might be going on below her, Diana chastely turned with the wind here until 1925, when the building was pulled down. By that time, Stanford White was dead, murdered in the very Garden of which he was so proud by a millionaire who didn't approve of his penchant for youthful female beauty.

Evelyn Nesbit's biographer, Paula Uruburu, likens Evelyn's photogenic appeal to Marilyn Monroe's: Evelyn's, too, was a presence the camera loved and made iconic, though unlike Marilyn she was initially perhaps more fatal to the men around her than to herself. Born in 1884, she outlived Marilyn by some five years and would have liked Marilyn to play her in the 1955 film about her early life,

The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing

, rather than the chosen star, Joan Collins.

Slight, fragile, with supple childlike limbs, copious hair that in the light moved from chocolate to auburn, a full mouth, glowing dark- hazel eyes and an inherent love of dressing up, this âAmerican Eve' had, in the early 1900s, an allure that met the period's demands for naughty but nice: she was both enticingly seductive and charmingly innocent. Evelyn could be chaste shepherdess, classical nymph, ragged Gypsy or playful coquette. She could wear the clothes the newly burgeoning fashion magazines demanded, yet needed none of the day's corsetry to advertise any of many products â soap, furs, chocolates, toothpaste.

She was the âmodern Helen', a dreamy, pouting pin-up girl for the new century. Dressed, half-dressed, veiled, behatted, chaste or seductive, Evelyn graced everything from tobacco and playing cards to calendars for Prudential Life and Coca-Cola. Charles Dana Gibson, illustrator for the mass market, twisted her hair into a question mark and transformed her into âWoman: the Eternal Question'. Her face came to embody the very mystery the eternal feminine posed. Eventually, even hard-bitten journalists would wax lyrical over her ingenuous charms. These were accompanied by a sharp, unschooled intelligence, which Stanford White, a Pygmalion to her Galatea, helped to educate, extending her native American to Shakespeare.

The evening of Monday, 25 June 1906 was unseasonably hot. It drove the rich to their Long Island homes and the rest to Coney Island. The day before, a hippo in the Brooklyn Zoo had expired in the heat, but on the 25th a sea wind tempered the weather just a little. Stanford White, then fifty-two, had taken his nineteen-year-old son Laurence and a friend, both students at Harvard, to dinner at the stylish Cafe Martin, a Paris look-alike establishment which even boasted a space devoted to women without escorts. Dinner over, White had dropped the younger men at the theatre they had chosen over the opening of what was advertised as âa sparkling musical comedy' in the rooftop space of Madison Square Garden.

The roof garden was a glamorous open-air cabaret-theatre. White's tower apartment and his luminous Diana overlooked it, and provided some of its visual drama. Lights of many colours twinkled and swayed amidst luxurious potted plants. Waiters carried drinks to the tables that took up the central space, and there were rows of seats at the sides. A special table was always reserved for White, the garden's creator. He was there for only part of that evening: he had seen bits of

Mamzelle Champagne

in rehearsal and it fizzed rather less than its title and advertising. But he was interested in one of the chorus girls, a seventeen-year-old new to the city, so he returned at eleven o'clock.

Soon after, a large muffled figure, with an unseasonable long black coat over his tux and a panama pulled down over his head, approached White's table from the lift towards which he and his party had seemed to be heading just moments before. A tenor was singing the ironically appropriate âI Could Love a Million Girls':

âI've heard them say so often they could love their wives alone,

But I think that's just foolish; men must have hearts made of stone.

Now my heart is made of softer stuff; it melts at each warm glance.

A pretty girl can't look my way, without a new romance ... '

A gunshot exploded in the night air, louder than both orchestra and crooner. It was quickly followed by two more. A woman screamed. Others joined in. White slid from the table, overturning it as he fell. Glass splintered everywhere. A doctor raced through the rising tumult to find him lying in a pool of blood, his face partly annihilated and blackened with powder burns. He was palpably dead and his killer stood beside him, his pistol now turned upside down, his arms held up over his head. He had been a mere two feet away from his victim and had put a first bullet through his left eye, a second through the mouth and a third through White's left shoulder. Some reported a look of glee on his face.

The theatre manager had ordered the orchestra to resume their playing and the chorus to be brought back on, but the performers were already leaving, joining the frightened crowd in what would at any moment turn into a stampede towards the exit. Others fainted on the spot. The mother of

Mamzelle

's lyricist, having watched the audience's hostile response to her son's opening night, feared he had been the object of attack and screamed, They've shot my son!'