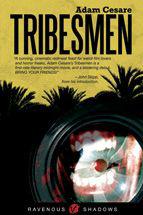

Tribesmen

Authors: Adam Cesare

Praise for

Tribesmen:

“

Tribesmen

is a gory and clever homage to those Italian cannibal flicks that we all love so dearly, but without the real-life animal cruelty! Highly recommended.”

–Jeff Strand, author of

Pressure

and

Wolf Hunt

.

“Sometimes everything goes wrong, in the best possible way. Think

Snuff

and

Cannibal Holocaust

meeting at a midnight movie. And then give one of them a camera, the other a knife.”

– Stephen Graham Jones, author of

It Came from Del Rio

and

Demon Theory

“The best new writer I’ve read in years. Wonderfully lean prose and edge-of-your-seat thrills. Drop everything else and start reading

Tribesmen

.”

–Nate Kenyon, author of

Sparrow Rock

and

Starcraft Ghost: Spectres

Content

Dedication

For anyone who’s ever been brave enough to pick up a camera in an attempt to make art...even if you didn’t succeed.

Acknowledgements

The two people most responsible for this book are my loving and supportive parents. If you’re going to blame anyone, blame them for not deterring their kooky son’s interest in horror.

Also of chief importance is John Skipp, writer and editor extraordinaire. Skipp took a chance on me, made this book the best it could possibly be, and I hope that one day I’ll be able to repay him.

On the homefront I’d like to thank my lovely girlfriend Jen, along with my best buddies and occasional-beta-readers Josh, Kyle and Phil.

Thanks also to my friends in the publishing industry. Nate Kenyon for being so generous with his time and expertise, Dallas and Kristy for the advice and book recommendations, and Christine and Dylan at

Paracinema

for their support of my film criticism.

Finally, warmest thanks to Debbie Rochon for the inspiration. Some say scream queen, I say

star

.

A LOVE LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

Dear Reader –

WELCOME TO RAVENOUS SHADOWS: a new line of frequently-savage, always-provocative genre fiction, dedicated to the proposition that short, powerful novels and novellas can pack as much punch, personality, and plot as books three times their size.

For example, take

this

crazy motherfucker!

Back in the distant 1980s, a slew of Italian jungle-based exploitation films with titles like

Cannibal Holocaust

and

Make Them Die Slowly

gobbled grindhouse marquees and international attention, often trumpeting in their advertising campaigns precisely

how many countries they’d been banned in

. Indeed, director Ruggero Deodato was dragged to court to prove that his actors had not been slaughtered in his hyper-realistic

mise-en-scene

. (Real animals died, which helped confuse the issue. And the fx were frankly astonishingly convincing.) The actors, unkilled, got Deodato off the hook.

If only the characters in this book were so lucky.

Now, decades later, a work of fiction finally expertly captures and

transcends

the insanity of those pictures and those times. A cunning, cinematic redmeat feast for weird film lovers and horror freaks, Adam Cesare’s

Tribesmen

is a first-rate literary midnight movie, and a blistering debut. BRING YOUR FRIENDS!

Then please feel free to check out the rest of the madness here at Ravenous Shadows, where the cool shit has just

begun

to hit the fan.

Yer horror-lovin’ pal,

John Skipp

Editor-In-Chief

1/22/2012

Prologue

THE ISLAND

The strangers had returned.

Both the rafts and their passengers were small white dots on the morning horizon. Oroto paid them little attention and tightened his grip on the thatched mesh of the fishing net. His son Vatu stood further up the shore, paying no attention to what he was doing. His dark eyes were fixed out over the ocean, watching the pale men approach.

“Pick up your end! Stop staring at the boats and help me,” Oroto barked, surprised at his own impatience with the boy. Every time they visited, Oroto’s son was fascinated by the men and their peculiar rafts. Vatu’s excitement would have to be curbed: this month over half of the village’s crop had already failed. Fishing was the only way Oroto was going to be able to feed his family. His son could waste time later.

Besides the fact that their skin was the color of sand, their hair that of dead grass and their language unintelligible, there was nothing particularly novel about the men. The travelers were permitted to come ashore the island a few times a season to trade. Without a common language, the men were forced to gesture for what they wanted. The pale men’s sign-language amused Vatu (and even some of the more ‘mature’ villagers) as they offered chickens and other less-than-useful trinkets in exchange for a place to sleep for the night.

Before the sun would rise the next morning, the men would be gone, embarking on the next step of whatever journey it was that they were making. Oroto didn’t particularly care who they were or where they were headed, as long as they paid his people for the privilege to stop.

On behalf of the islanders, Oroto and his family were voted the brokers of these deals. Oroto was always glad to take the chickens, and his mother would then divide the rest of the take amongst the tribe. No one ever complained about the arrangement. The people of the island respected age, and there was no islander older than Oroto’s mother. None of the islanders seemed to care much whether strangers bedded down on their meager piece of land for the night, as long as they weren’t carousing or bringing their white devil gods with them off of their boats.

“Where are the chicken cages?” Vatu asked. He squinted against the light to make out the approaching visitors, shading his eyes with one of his small black hands.

“Maybe this time they will bring us fish,” Oroto said, softening his chastisement. “We’re going to need them, too, because I have a lazy son who catches nothing but sunshine and questions.”

Vatu gave a short giggle before he went silent and returned to casting out the fishing net. The boy had caught a glimpse of his father’s serious expression, and one stern look was all that Oroto needed to use.

The pale men were taking their time. They were not rowing yet, but instead allowed the ebb of the tide to pull them closer to the island. This was odd, but even more abnormal still was the large number of rafts they had arrived with today. Five hollowed-out crafts with three to four passengers each.

“The bones,” a voice called from the end of the beach.

Oroto turned towards the jungle to see his mother running out of the clearing. Puffs of sand flew up as she trudged down the upper part of the beach as fast as her gnarled legs could carry her.

Oroto let go of the fishing net and ran up the beach to meet his mother. As he closed the distance he yelled back to Vatu. He had to make sure that the boy brought in the rest of the fish.

His mother collapsed to her knees before he could reach her. Her small body was wracked with sobs as she writhed, clawing at the sand. Oroto placed one strong hand on her back, feeling the bumps of her spine as they jumped up and down with her cries.

“What bones?” Oroto asked, but he knew exactly what the old woman had meant. She had been up to her magic again. She used an odd collection of chicken bones and broken boar’s tusks to look into the future. Or so she claimed.

She had collected the bones over her long lifetime, tossing them up into the air and making notes in the sand as to how they fell. With these bones she read the fortunes of the girls in the village. Normally, she used the practice to see who would be married and who would soon be pregnant: she was more of the village matchmaker than she was a psychic. The bones had never made her this upset.

“What is it mother? What did you see?” Oroto helped her to her feet and glanced back to see Vatu hurrying to gather up the net and the few small fish inside it.

Beyond the boy, he could now just make out the faces on the men in the first raft. Their faces were red, not the usual tannish-white. Also the men were rowing now, apparently no longer content to coast into shore.

“Call Vatu in to us,” she said, and then she screamed out to the boy herself before Oroto had the chance: “Leave that, run up here!” Vatu looked at his grandmother, puzzlement etched into his face, then back to his father.

Oroto was hesitant to wave the boy in. Vatu held the net firmly in his grasp, reluctant to drop it before Oroto told him to do so. It would be a shame to waste the fish on the orders of a superstitious old woman.

“Please call him in,” his mother said, squeezing Oroto’s hand in hers. Oroto could feel the dry folds of her old skin, and her earnestness made his decision for him.

“Hurry up, boy,” Oroto said, glancing beyond his son again, looking at the fast-approaching boatfuls of white men.

Then Oroto saw it. Blood. It was blood turning the white men red. They were covered in it from head to belly.

He then noticed that the lead man in the second raft was not a man at all, but instead a skinned corpse, propped up like a masthead. The corpse’s skin was flayed, stretched across the back of the second raft and drying in the morning sun.

The men at the front raft were rowing with supernatural speed now. Seafoam frothed up from the ends of their oars and a fine mist enveloped the bow of their little craft. Behind them, the other four boats were following suit. There were never more than two rafts of white men at a time, but now there were five.

Vatu gathered up the net in both hands, juggling the two or three fish trying to flap their way to freedom. Oroto urged him on, and he dropped the net, beginning to run from the churning surf. Despite Vatu’s constant insistence that he was nearly a man, the boy still had the ungainly waddling gait of a child.

His son was oblivious to the men that, a few minutes prior, he could not take his eyes off.

The men in the rafts were maybe twenty meters from shore when the first of them jumped off the side of his vessel. The big, bearded man splashed into the water. It was shallow enough to stand, and the line of the crystal blue water came up to the middle of his bloodied chest. The spot where he hit the waves immediately exploded into a cloud of burnished red.