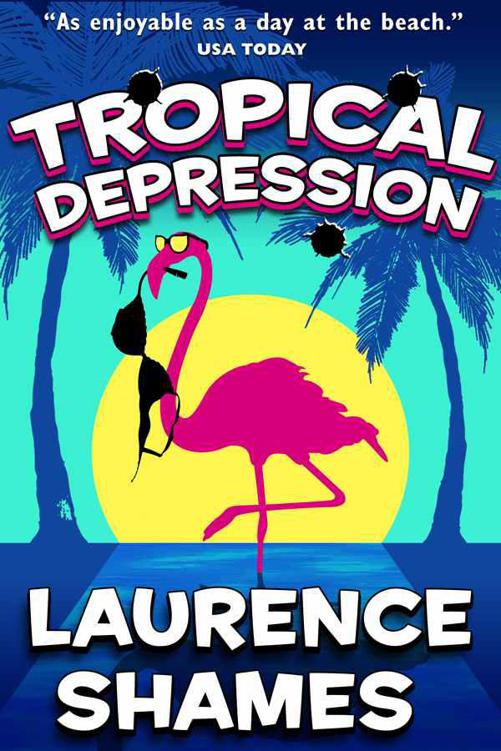

Tropical Depression

Read Tropical Depression Online

Authors: Laurence Shames

PRAISE FOR TROPICAL DEPRESSION

"Tropical Depression flies high."

—The New York Times

"As tasty as a mango sundae." —

New York Daily News

"It's hilarious."—

Playboy

"Another winner for Shames."—

Booklist

"Key West is another country. And Shames is its pop storyteller nonpareil."—

Newark Star Ledger

"Nothing short of hilarious."—

Pittsburgh Tribune-Review

"Funny, cleverly written, and a delightful read. A day at the beach."—

Syracuse Herald American

"Tropical Depression is Shames at his finest. If you can't do Florida this week, this is the next best thing."—

Detroit Free Press

Tropical Depression

By

Laurence Shames

Copyright ©1996 Laurence Shames

Smashwords Edition, License Notes

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be resold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to Smashwords.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

For Marilyn, my wife—

absolutely, indisputably, once and for all, the best

In the writing of this book I have been

immeasurably helped by a brilliant editor,

a stellar agent, and vice versa. Hearty

thanks to Brian DeFiore and Stuart

Krichevsky, the kinds of allies that every

writer dreams of having some day.

1

When Murray Zemelman, a.k.a. the Bra King, started up his car that morning, he had no clear idea whether he would go to work as usual, or sit there with the engine idling and the garage door tightly shut until he died. He was depressed, had been for several months. His mind had shriveled around its core of gloom like a drying apricot around its pit, and he saw no third alternative.

So he sat. He looked calmly through his windshield at the gardening tools put up for the winter, the rakes and saws hung exactingly on Peg-Board, his worthless second wife's golf bag suspended at a coquettish angle by its strap. The motor of his Lexus softly purred, nearly odorless exhaust turned bluish white in the chilly air. He breathed normally and told himself he wasn't choosing suicide, wasn't choosing anything. He was just sitting, numb, immobilized, gripped by an indifference so unruffled as to be easily mistaken for a state of grace.

Then, in a heartbeat, he was no longer indifferent. Anything but. Maybe it was just a final squirt of panic before the long oblivion. Maybe the Prozac, as dubious as vitamins in its effect these last few weeks, had suddenly kicked in.

Murray said aloud, "Schmuck! Schmuck, you fuckin' nuts?"

He reached for his zapper, flashed it at the garage door's electric eye. The wooden panels stretched, then started rolling upward, but not quite fast enough for Murray in his newfound rage to live. He threw the gearshift into reverse and stomped on the accelerator. Tires screeched on cold cement, the trunk caught the bottom of the lifting door. Varnished cedar splintered; champagne-colored paint scraped off the car; snaggled boards clawed at its metal roof. The bent garage door rose almost to the top of its track, then jammed, the mechanism whirred and whined like a Mixmaster bogged in icing.

Murray Zemelman, gasping and sweating on his driveway, opened his window and sucked greedily at the freezing air with its smells of pine and snow. He coughed, gave a dry and showy retch, mopped his clammy forehead. A shudder made him squirm against the leather seat, and when the long spasm had passed, he felt mysteriously light, unburdened. New. He felt as though a pinching iron helmet had been taken from his head and a grainy gray diffusing film swept clean from his eyes. He blinked against the sidearm brightness of a January sunrise; in his refreshed vision, the glare became a glow that caressed objects and displayed them proudly, like a spotlight that was everywhere at once.

Amazed, Murray looked at his house, looked at it as if he'd never seen it before. It was a nice house, a grand house even—big stone chimney, portico with columns—and in his sudden clarity he was able to acknowledge, not with sorrow but ecstasy, that he hated it. Yes! He hated every goddamn tile and dimmer switch and shingle. This was not the house's fault, he understood; but nor was it his. He'd worked his whole life to have a house like this; he'd paid through the nose to own it. By God, he was allowed to hate it. To hate the plaid-pants town of Short Hills, New Jersey, where it stood. To hate the dopey high-end gewgaws that cluttered up the living room. To hate the stupidly chosen second wife curled in bland, smug, already-fading beauty on her own side of the giant bed.

He hated all of it, and in the wake of the nasty and forbidden joy of admitting that, came a realization as buoyant as the feeling of flying in a dream: He didn't have to be there.

He didn't have to be there; he didn't have to go to work; he didn't have to kill himself. He remembered with surprise and awe that the world was big, and for the first time in what seemed like forever, he had a fresh idea.

He wheeled out of his driveway, burned rubber around a sooty snowbank, and headed for the Parkway south.

*****

He drove all day, he drove all night, giddy and relentless in his quest for warmth and ease and differentness.

At nine-thirty the next morning, he was draped across his steering wheel, dozing lightly in yellow sunshine cut into strips by the tendrils of a palm frond. His back ached, his jowls drooped, his hips and knees were locked in the shape of the seat, but he'd outdistanced 1-95, barrelled to the final mile of U.S. 1. He'd made it to Key West.

By first light he'd found a real estate office called Paradise Properties. He'd parked his scratched-up Lexus at a bent meter and then contentedly passed out.

He was awakened now by a light tapping on his windshield.

He looked up to see a slightly built young man in blue-lensed sunglasses. The young man made his hands into a megaphone. "Looking for a place?"

"How'd ya know?" said Murray, rolling down the window.

"Jersey plates," the young man said, more softly. "Ya got a tie on. And, no offense, you're very pale." He held out a hand. "Joey Goldman. Come in when you're ready, we're putting up coffee."

Murray yawned, climbed out of the car, tried to stretch but nothing stretched. He saw yellow flowers, flowers on a living tree in January. He sucked air that smelled of salt and iodine, air the same temperature as his face. He smiled tentatively, then dragged himself into the office.

Joey Goldman, at his desk now, regarded him. Joey had lived in Key West half a decade. He knew that almost everyone who came there, came there on vacation—and there was nothing duller in the world than a person on vacation. Some came to snorkel and drink. Others came to drink and fish. Some came to chase sex while drinking. Others just drank. But one visitor in a thousand, Joey had observed, probably more like one in ten thousand, was not a tourist but a refugee. Sometimes it was refugee as in fugitive. Sometimes it was refugee from a monster spouse or lover, or from a northern life that had finally hit the wall. Joey looked at the new arrival's houndlike bloodshot eyes, his kinky graying wild hair, his rumpled shirt and posture that somehow seemed exhausted and frenetic all at once. He decided that maybe the frazzled fellow was not there on vacation.

"So, Mr.—"

"Zemelman. Murray Zemelman."

"Some coffee, Mr. Zemelman?"

Murray nodded his thanks and an assistant brought over a cup for him.

Joey said, "What can I do for you?"

Murray held his java in both hands and gave a little slurp. "Place on the ocean."

"Onnee ocean," Joey said, "that'd have to be a condo. No rental houses onnee ocean."

"Condo's fine."

Joey cleared his throat. "What price range—"

"Someplace nice."

"You know the town?"

"Not well," said Murray. "I was here once, twelve, maybe fifteen years ago."

"Ah," said Joey.

"With my first wife," the Bra King volunteered.

"Ah. Well—"

"And yesterday I was thinking," Murray rambled. "I don't mean thinking like

trying

to think, I mean the thought just came to me, out of the blue, that maybe it was the last time I really had fun."

Joey riffled through his boxful of listings.

"The crazy things ya remember," Murray went on. "This old Spanish guy, big hairy birthmark on his cheek, like four feet tall. Had a big block of ice on a cart. Shaved it by hand, with a whaddycallit, a plane. Put it in a paper cone with mango syrup. Franny loved it. Cost fifteen cents."

Joey pulled out an index card. "You know where Smathers Beach is, Mr. Zemelman?"

Murray blinked himself back to the present. "By the airport, no?"

"Up that way," said Joey. "There's a condo there, the Paradiso."

" 'S'nice?"

"Very nice. Coupla former mayors live there. State senator lives there when he's not up at the capital."

Murray yawned.

"There's a penthouse available," Joey went on.

"Penthouse?" Murray said. "Like thirty stories up?"

"Like three stories up. We're not talkin' Miami. It's a little pricey—"

"On the ocean?"

"Across the road. We're not talkin' Boca. Three bedrooms. Three baths. Master suite has Jacuzzi—"

"Okay," Murray said.

"Okay what?

"Okay I'll take it."

"You don't wanna see it first?" said Joey.

Murray shrugged dismissively and reached into a pocket for his checkbook. "Company check okay?"

"Fine," said Joey. "It's five thousand a month and they'll want a month's security."

"I'll take three months for now," said Murray, and he wrote a check for twenty grand.

Joey took it and examined it briefly, discreetly. The company name rang a bell. "Hey, wait a second," he said. "BeautyBreast, Inc. Murray Zemelman. I thought you looked familiar. The guy that does the ads, right? Late at night. Wit' the crown. The Bra King crown. Always wit' the women in their bras."

"My bras," Murray corrected softly.

"Dancin' with 'em," Joey remembered. "Bowling, playing volleyball—"

Murray nodded modestly.

"My favorite?" Joey said. "The opera one, the one where all these women in their bras got spears and shields, and you come down, what're you wearin', a bathrobe, somethin?—"

"Toga," said the Bra King. "I didn't know they aired down here."

"Me, I'm from New Yawk," said Joey. "Everybody here, they're from somewhere else." He opened a desk drawer, pawed his way through many sets of keys. "The Bra King," he muttered, "whaddya know .. . Okay, this is them. The square key, it's for the downstairs lock. The round one's for the penthouse. There's three buildings, like in a U around the pool. You want West. Got it?"

Murray took the keys and nodded.

Joey shook his hand, stole a final look at him, almost spoke, but realized it would be indiscreet to ask if they touched his hair up for TV.

Maybe it was Prozac, maybe it was glee. Was there a difference? Did it matter?

It didn't matter to Murray. Gleefully, he drove through the narrow streets of Old Town, his brain awash in juices that tickled, enzymes that made hair triggers of each synapse. Everything delighted him: bawdy clusters of coconuts dangling under skirts of fronds; purple bougainvillea that swallowed up white fences; the breath-damp air whizzing over his furry arm as it rested on the window frame. He wound his way to A-1A and clucked with pleasure at the sunshot green of the ocean, the green-tinged bottom of a distant cloud. By the time he found the Paradiso condo, his chest was tight, the unaccustomed elation strained his heart like unprepared-for exercise.

Still, his step was blithe as he moved to what he thought was the West Building of the complex and opened up the downstairs door. He got in the elevator, reveling in the naked lightness of traveling with nothing whatsoever, starting a new life without so much as a familiar coffee mug from the old. He rode to the third floor, went the wrong way down the corridor, then wheeled and found the penthouse. By a mix of filtered sunlight and flickering fluorescent, he tried his key in the door. It didn't work.

He withdrew it, tried it upside down. He went back to the first way. He finessed, he jiggled. He was stooped over the lock, one hand on the key and the other on the doorknob, when the door was suddenly, violently yanked open, pulling the Bra King halfway into someone else's unit.

Bewildered, guilty, feeling like a burglar in a dream, Murray Zemelman looked meekly up. He saw an Indian. A very angry Indian who was wearing a chamois vest with fringes and jabbing a thick finger back toward someone Murray couldn't see.