Tutankhamen (18 page)

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Inscriptions show that some of Tutankhamen's

shabtis

were dedicated by the courtiers Maya and Nakhtmin, who presumably wished to be associated for eternity with their newly divine king. This is not unusual; the tomb of Yuya and Thuya included an elaborate throne or chair dedicated by their most prominent granddaughter, Princess Sitamen. However, we have no idea how the system worked.

shabtis

were dedicated by the courtiers Maya and Nakhtmin, who presumably wished to be associated for eternity with their newly divine king. This is not unusual; the tomb of Yuya and Thuya included an elaborate throne or chair dedicated by their most prominent granddaughter, Princess Sitamen. However, we have no idea how the system worked.

Given our own association of flowers with funerals, it is tempting to imagine Tutankhamen's funerary wreaths being donated by well-wishers, although this is probably an assumption too far. The Egyptians, like us, associated flowers with funerals, and several of the rewrapped royal mummies were provided with garlands by their restorers. Tutankhamen had flowers incorporated within his coffins: a wreath adorning the uraeus of the second coffin, a pectoral garland lying on the chest of the second coffin and a floral collar lying on the third coffin. None of these were well preserved â like the bandages, they had become hard and brittle â but Percy Newberry was able to determine that they were flowers which bloomed from the middle of March to the end of April.

18

Assuming that Tutankhamen spent the

usual seventy days in the embalming house, this would suggest that he died in January or February.

18

Assuming that Tutankhamen spent the

usual seventy days in the embalming house, this would suggest that he died in January or February.

Not all of Tutankhamen's grave goods were new: some had clearly been used â presumably by him â and some bore the earlier form of his name, Tutankhaten, rather than Tutankhamen, indicating that they were made within the first few years of his reign. Along with the childhood clothing there were earrings, which, during the 18th Dynasty, were worn by children and women but not by adult men. The rather large piercings in Tutankhamen's empty ears were presumably the legacy of a childhood spent wearing wide ear studs.

19

Perhaps the most personal item of all was the empty box whose label Carter translates as âThe King's side lock (?) as a boy'; the side-lock being the long plait of hair worn by children on the side of their otherwise bald heads.

20

It is tempting to speculate that these items were included in the tomb for sentimental reasons: many people find it immensely comforting to have their own property around them at times of stress. Alternatively, it may simply be that all items discarded by a king â including his hair â were routinely saved for inclusion in his burial.

19

Perhaps the most personal item of all was the empty box whose label Carter translates as âThe King's side lock (?) as a boy'; the side-lock being the long plait of hair worn by children on the side of their otherwise bald heads.

20

It is tempting to speculate that these items were included in the tomb for sentimental reasons: many people find it immensely comforting to have their own property around them at times of stress. Alternatively, it may simply be that all items discarded by a king â including his hair â were routinely saved for inclusion in his burial.

Sentimental attachment may also explain the presence of what Carter categorised as âheirlooms': artefacts inscribed with the names of deceased royal family members, including Tuthmosis III, Amenhotep III, Tiy, Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Meritaten and âNeferneferuaten'. It is not always clear whether these are genuine heirlooms, or simply old artefacts somehow acquired and re-used by Tutankhamen. What are we to make, for example, of faience bangles, recovered from the Annexe, inscribed with the names of Akhenaten and Neferneferuaten? That Tutankhamen did âborrow' from others is made clear by those pieces of jewellery whose cartouches have been altered to give Tutankhamen's name. Other pieces â such as the pectoral ornament displaying a beetle (kheper) pushing the sun disc (re), which forms a rebus reading âNeb-kheperu-re' (Tutankhamen) â were clearly made for him.

Â

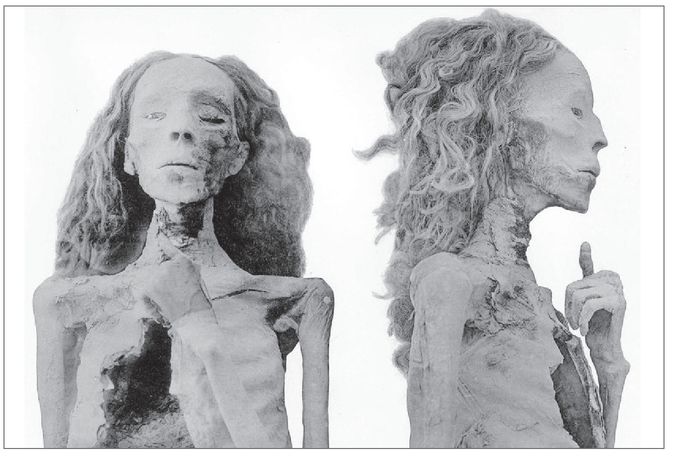

10. The âElder Lady' discovered in the Amenhotep II cache of royal mummies and believed by many to be Tiy, consort of Amenhotep III and mother of Akhenaten.

The most intriguing of the âheirlooms' was discovered in the Treasury. At first sight it was nothing spectacular: a small, wooden anthropoid coffin which had been coated in resin, bound with linen strips and sealed with the necropolis seal. Inside this, however, was a second coffin, and inside this second coffin a third coffin plus, wrapped in a piece of linen, a solid gold statuette of a squatting king wearing the blue crown. This figure, which was designed to be worn as a pendant, has been identified on stylistic grounds as either Amenhotep III or Tutankhamen himself. Within the third coffin was a fourth miniature coffin, anointed and sealed, which bore the name and titles of Tiy, consort of Amenhotep III, and inside this coffin was a plait of hair, carefully folded in a linen cloth. Scientific analysis indicated that this hair matched the still abundant hair on the head of the âElder Lady' (KV 35EL), one of the three unwrapped mummies discovered in a side chamber of the tomb of Amenhotep II:

â¦a small, middle-aged woman with long, brown, wavy, lustrous hair, parted in the centre and falling down both sides of the head on to the shoulders. Its ends are converted into numerous apparently natural curls. Her teeth are well-worn but otherwise healthy. The sternum is completely ankylosed. She has no grey hair. She has small pointed features. The right arm is placed vertically-extended at the side and the palm of the hand is placed flat upon the right thigh. The left hand was tightly clenched, but with the thumb fully extended; it is placed in front of the manubrium sterni, the forearm being sharply flexed at the brachium.

21

21

For a time it was unquestioningly accepted that the Elder Lady must be Tiy, even though, at apparently no more than forty years of age, she was perhaps less elderly than might have been expected. However, doubts then started to arise over the accuracy of the analytical technique and this, along with the somewhat late realisation that a name on a box cannot by itself prove the ownership or origin of anything within that box, meant that the identity of the Elder Lady was not as cut and dried as was once supposed.

22

In 2010 scientists working for the Egyptian Antiquities Service under the leadership of Dr Zahi Hawass used genetic analysis to identify KV 35EL as the grandmother of Tutankhamen and the daughter of Yuya and Thuya: an identification which has been generally accepted.

23

22

In 2010 scientists working for the Egyptian Antiquities Service under the leadership of Dr Zahi Hawass used genetic analysis to identify KV 35EL as the grandmother of Tutankhamen and the daughter of Yuya and Thuya: an identification which has been generally accepted.

23

No amount of sentimental attachment can sensibly explain why a significant number of Tutankhamen's most intimate grave goods â his middle coffin, mummy bands, canopic chest and miniature canopic coffins â were originally made for someone else. Their re-use is made obvious by their style â the facial features resemble neither Tutankhamen's death mask nor his innermost and outermost coffins, but do

resemble the coffin found in KV 55 â and by their inscriptions, which betray signs of alteration. Style makes it equally obvious that this equipment belongs to the late Amarna period. These are not the long-lost grave goods of the pyramid kings, they are grave goods prepared for a person or people known to Tutankhamen: a member of his family. Most experts now accept that they were originally made for âNeferneferuaten', an enigmatic individual or individuals of unknown gender who has been variously equated with Nefertiti, her eldest daughter Meritamen and Tutankhamen's immediate predecessor, Smenkhkare.

resemble the coffin found in KV 55 â and by their inscriptions, which betray signs of alteration. Style makes it equally obvious that this equipment belongs to the late Amarna period. These are not the long-lost grave goods of the pyramid kings, they are grave goods prepared for a person or people known to Tutankhamen: a member of his family. Most experts now accept that they were originally made for âNeferneferuaten', an enigmatic individual or individuals of unknown gender who has been variously equated with Nefertiti, her eldest daughter Meritamen and Tutankhamen's immediate predecessor, Smenkhkare.

These were essential items. A king might be interred without food, clothing or childhood memorabilia, but would need his coffin and his canopic jars to help him achieve a full rebirth. Why then did Neferneferuaten not need this equipment? It may simply be that these were unwanted spares, unused by Neferneferuaten and subsequently retrieved from the royal workshop. But it seems far more likely that Tutankhamen, or those who buried him, âborrowed' them either directly from Neferneferuaten's own tomb or more indirectly from KV 55, which, as we have already seen, contained a series of items gleaned from various Amarna burials. KV 55 confirms that Tutankhamen was not squeamish about re-opening tombs, moving mummies and recycling funerary artefacts. Indeed, the evidence provided by the two royal caches, although somewhat later in date, suggests that reusing the grave goods of the ancestors was a standard, if not well-advertised, procedure. This would certainly explain why tomb robbery was ranked among the most serious of Egyptian crimes, punishable by an unpleasant death by impaling. Not only were tomb robbers denying the dead their chance of eternal life, they were stealing valuable state assets.

We may guess how Tutankhamen acquired Neferneferuaten's goods. Why he needed them is a different matter. We might have expected that all Tutankhamen's coffins and canopic equipment were

made early in his reign and stored in a place of safety â the royal workshop perhaps, or his memorial temple â until required. Tutankhamen, however, was not a typical king. Might his craftsmen have waited until their king reached maturity, uncertain not only about his eventual size but also about his eventual religious beliefs? Could this delay explain why he lacked essential items? Or could it simply be that he could not afford a full set of grave goods? Alternatively, was Ay responsible? Tutankhamen may have planned his own burial, but there was nothing that he could do to ensure that his plans were implemented. In the absence of a son who might be presumed to have a father's best interest at heart, he was dependent on Ay's goodwill. Contrary to much published fiction, there is no evidence to suggest that Ay was in any way Tutankhamen's enemy. However, Ay was an elderly man who might reasonably have feared dying before his own royal funerary preparations were complete. Usurping Tutankhamen's grave goods, and substituting items taken from the handy KV 55 cache, may well have seemed a prudent idea.

made early in his reign and stored in a place of safety â the royal workshop perhaps, or his memorial temple â until required. Tutankhamen, however, was not a typical king. Might his craftsmen have waited until their king reached maturity, uncertain not only about his eventual size but also about his eventual religious beliefs? Could this delay explain why he lacked essential items? Or could it simply be that he could not afford a full set of grave goods? Alternatively, was Ay responsible? Tutankhamen may have planned his own burial, but there was nothing that he could do to ensure that his plans were implemented. In the absence of a son who might be presumed to have a father's best interest at heart, he was dependent on Ay's goodwill. Contrary to much published fiction, there is no evidence to suggest that Ay was in any way Tutankhamen's enemy. However, Ay was an elderly man who might reasonably have feared dying before his own royal funerary preparations were complete. Usurping Tutankhamen's grave goods, and substituting items taken from the handy KV 55 cache, may well have seemed a prudent idea.

Tutankhamen's sarcophagus was in far from pristine condition when he was interred. It wasn't even one piece; the body was carved from a single block of yellow quartzite, while the sloping lid was carved from red granite which had been painted yellow in a crude attempt to match the base. The lid was decorated with a winged sun disc at the head end, and three vertical lines of hieroglyphic funerary text. The base, which also bore hieroglyphic texts, was protected by four funerary goddesses carved in raised relief, one at each corner. Isis (north-west), Nephthys (south-west), Serket (south-east) and Neith (north-east) stood with their winged arms outstretched so that they completely encircle the sarcophagus, embracing and protecting Tutankhamen. Their role as the four female guardians of the dead was an ancient one, already well

established by the Old Kingdom. However, it is clear that the base has undergone extensive alteration, and that the four goddesses originally had human arms rather than feathered wings. This suggests that they were conceived as mortals, possibly queens, and that they only became divine following the change in official religious beliefs in the earlier part of Tutankhamen's reign. A parallel may be drawn with Akhenaten's badly damaged sarcophagus, fragments of which have been recovered from the royal tomb at Amarna. Akhenaten's mythless religion denied the existence of the traditional deities, and his sarcophagus was protected by four images of his consort, Nefertiti, standing at its corners. Nefertiti's status in this context is debatable; is she protecting her husband's coffin in her role as a dutiful wife, or is she a living goddess? Either way, this parallel suggests that Tutankhamen's sarcophagus, if indeed it was originally intended for him, might have borne four protective images of his consort, Ankhesenamen.

24

established by the Old Kingdom. However, it is clear that the base has undergone extensive alteration, and that the four goddesses originally had human arms rather than feathered wings. This suggests that they were conceived as mortals, possibly queens, and that they only became divine following the change in official religious beliefs in the earlier part of Tutankhamen's reign. A parallel may be drawn with Akhenaten's badly damaged sarcophagus, fragments of which have been recovered from the royal tomb at Amarna. Akhenaten's mythless religion denied the existence of the traditional deities, and his sarcophagus was protected by four images of his consort, Nefertiti, standing at its corners. Nefertiti's status in this context is debatable; is she protecting her husband's coffin in her role as a dutiful wife, or is she a living goddess? Either way, this parallel suggests that Tutankhamen's sarcophagus, if indeed it was originally intended for him, might have borne four protective images of his consort, Ankhesenamen.

24

Texts and illustrations from Thebes and Amarna confirm that Ankhesenamen, formerly known as Ankhesenpaaten, was the third of the six surviving daughters born to Akhenaten and his consort Nefertiti. At Amarna she appeared regularly as a little girl in âinformal' family groups with her parents and sisters. Here, like all the princesses, she had a curious, elongated, egg-shaped head; the egg being a potent symbol of creation which served to link Akhenaten's semi-divine family with his god. As she was born before the end of Akhenaten's Year 7, and probably a year or two before that, Ankhesenamen would have been approximately six years older than Tutankhamen. Assuming that they married as he became king, he is likely to have been eight years old; she would have been fourteen.

Other books

The Unnamable by Samuel beckett

Flying to Nowhere: A Tale by Fuller, John

Queen of Jastain by Kary Rader

The Sacrifice Stone by Elizabeth Harris

His Royal Pleasure by Leanne Banks

Descendant by Eva Truesdale

Stealing Snow by Danielle Paige