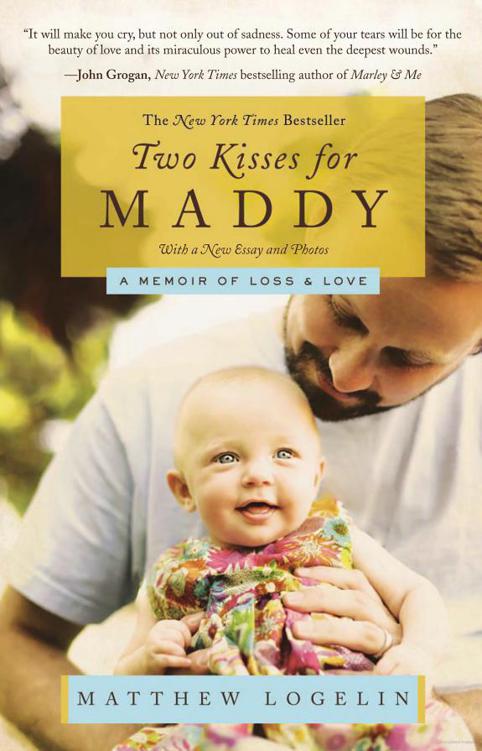

Two Kisses for Maddy: A Memoir of Loss & Love

Read Two Kisses for Maddy: A Memoir of Loss & Love Online

Authors: Matthew Logelin

Tags: #General, #Marriage, #United States, #Family & Relationships, #Personal Memoirs, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Death, #Grief, #Case Studies, #Spouses, #Mothers, #Single Fathers, #Matthew - Family, #Logelin; Matthew, #Single fathers - United States, #Logelin; Matthew - Marriage, #Matthew, #Loss (Psychology), #Matthew - Marriage, #Mothers - Death - Psychological aspects, #Single Parent, #Widowers - United States, #Bereavement, #Parenting, #Life Stages, #Logelin, #Infants & Toddlers, #Infants, #Infants - Care - United States, #Widowers, #Logelin; Matthew - Family, #Spouses - Death - Psychological aspects, #Psychological Aspects

for madeline.

I

am not a writer.

At least, I didn’t think I was. But in your hands you hold a book that I wrote.

I wish I hadn’t had a reason to write this thing. On the morning of March 25, 2008, my life was the best I ever imagined it could be; an instant later, everything would change. More on that soon, but first I want to share a couple of stories.

I’ve always been of the mind that great art can only come from a place of immense pain (mostly because I hate happy music), and that the resulting work is beautiful because it is motivated by the purest and most authentic of emotions: sadness. I’ve never believed so strongly in this axiom as I did in the two moments I’m about to describe…

September 2000. I was living in Chicago, working my way through the first year of graduate school. While reading Marx, Weber, and Durkheim for my sociological theory class, I discovered a song that, more than any other had so far, altered my perspective: “Come Pick Me Up” by Ryan Adams. It was the kind of song I wished I could write—it was sad, it was funny, and it included the word

fuck.

But I loved it mostly because it was sad. The words made me feel something I’d never felt before: hearing the swelling pain of that song made me yearn for the kind of heartache that would allow me to create something—anything—so amazing.

After listening exclusively to this song for a couple of days, I called my girlfriend to tell her about it. “I think I could probably write a song like this, but you’ve been way too good to me.” Liz and I had been dating for just over four years at that point, and we had what I considered a nearly perfect relationship. She had never caused me the kind of agony that would allow me to tap into whatever creative side may have been hiding deep within me. And as much as I wanted to write The Next Great Depressing Song, I was glad that I hadn’t had the ability—or the need—to do so.

May 2006. I was living in India for a work assignment, and half way through my stay, Liz came to visit. I took a few weeks off so we could travel the country and see things we never imagined we’d have a chance to see. I had a long list of places for us to visit, but Liz insisted we get to one site in particular: the Taj Mahal. Standing in front of one of the Seven Wonders of the World, we listened to our guide tell us the story of how it came to be. He explained that the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan had ordered its construction to fulfill a promise to his wife. Legend has it that on her deathbed—shortly after giving birth to their child—she asked her husband to build her a monument that would forever be known as the most beautiful in the world.

I rolled my eyes, wondering if the story was even true or if it was something the guides fabricated to make female tourists swoon, but Liz was feeling every word of it. She stared in awe at the mausoleum, her eyes welling with tears and her lips agape. Her sweaty hand squeezed mine tighter and tighter as our guide continued the story. When he finally finished, Liz turned to me and said, “You would never do something like this for me.”

She was right—I can’t build anything. I can barely hang a picture on the wall. But I never imagined a need to do such a thing.

As I began putting this book together, these two stories stuck in my head, and they swirled around and intertwined and coalesced while I wrote it and revised it. They were a huge spark. I hadn’t forgotten about that song, and I hadn’t forgotten about that trip, but before Liz died, I had forgotten exactly what they’d meant to me.

I know that this book is no “Come Pick Me Up” and it’s most certainly no Taj Mahal, but it is my attempt to turn my sadness into something beautiful. It is mine. Mine for Liz. And no matter what, I know that she would be proud of me.

And I guess you could say that I am a writer now. But I really wish I wasn’t.

it seemed obvious

(though probably only to us),

that we’d

spend the rest of

our lives

together.

I

met my future wife, the future mother of my child, at a gas station. It was a Tuesday in late January 1996, and we were both eighteen years old. Though we lived fewer than two miles apart, this was only the second time we had met, as we went to different high schools and ran with different crowds. But that night, when she saw me just a few feet away, Liz Goodman waved and said, “Are you Matt Long-lin?” She mispronounced my name, but it was close enough. An awkward and shy teenager lacking a lot of self-confidence, I was shocked when this beautiful blonde girl started talking to me. It was weird at first—girls like Liz didn’t talk to boys like me, so I figured she thought I worked at the gas station and she needed some help filling her tank. I responded with a confused look and sheepish “Yeah. That’s me,” and continued filling my own tank. I was instantly captivated by Liz’s gregariousness, her moxie, and, of course, her beauty. She stood at exactly four feet eleven inches tall, but carried herself like she was six feet one. Years later, she would tell me that I had impressed her by holding the door open for her when we walked into the little store to pay. I would counter with my surprise that an act as small as that could convince her to see past my unquestionably awkward looks.

We went on our first date that Friday, January 26. Three days later, standing in her parents’ driveway, Liz let the L word slip from her lips. I responded with a smile, a kiss, and an “I love you, too,” and we were both positive that this was it: we’d both found the person of our dreams. We were just a few months away from heading off to college in different states (I was staying put at St. John’s in Minnesota, while Liz was off to Scripps in California), so we became almost inseparable, wanting to make the most of the short time we had left together in the same town.

During my spring break trip to Mexico, I purchased calling cards with money that ordinarily might have been used on beer and admission to clubs, and spent almost the entire trip talking to Liz from pay phones while my friends got drunk and made out with random girls. I’m pretty sure I was the only eighteen-year-old male in Mazatlán doing this on his spring break. A month after my return from the trip, Liz was off to Spain, spending three weeks living with a host family as part of a program designed to get high school seniors out of their comfort zones and into a new environment. While there, she used her dad’s calling card to talk to me multiple times each day, running up a phone bill so enormous and so shocking that to this day her dad still remembers the amount, down to the penny. As fall approached and we prepared to head off to college, we promised each other that the distance would not come between us. Thanks to these short practice runs, we were confident that we’d be one of those rare high school couples that would make it all the way through our college years with our relationship—and sanity—intact.

In fact, the distance intensified our relationship—we had to work much harder than the couples we knew who weren’t worrying about being apart. Phone and webcam communication became integral so that we could study “together.” And no matter where we had been or how late we had been out, we exchanged e-mails nightly. During our four years in college, Liz only missed out on sending four of them compared to my six—a fact that she liked to throw in my face whenever I gave her shit about something later on. When we were able to be together in between our time apart, we truly appreciated it and showed it by walking arm-in-arm through the tree-lined sidewalks of Claremont. Liz spent the money she earned from her on-campus job along with the monthly stipend from her parents to fly me out to California every six to eight weeks. She figured that because she was paying, I should do the flying, and I knew better than to put up a fight. She did visit me enough times for us both to realize that we had more fun together in California anyway. During our summers home, we worked less than half a block apart, using our lunch breaks to make up for the time we had lost during the school year.

Our junior years, we both decided to study abroad for a semester, but knowing one would influence the other’s decision, we agreed to discuss our chosen destinations only after the applications had been submitted. Even with a literal world of choices before us, we both picked London. It was incredible to be living in the same city at the same time, without our parents. We both truly felt like we were out in the world on our own for the first time in our lives, but we didn’t spend every waking moment together for fear of seriously affecting the other’s experience. I know that sounds strange, but we believed that we should continue on as if we were in different parts of the country so that we could both fully experience our semester abroad—but now, we were a forty-five-minute tube ride apart, rather than a four-hour flight. After we finished our studies in London, Liz took off with her friends, and I with mine, to travel around Western Europe. We made a plan to meet up after two weeks, ditch our friends, and travel alone, together. Our paths converged on the island of Corsica, and that was where things changed for both of us. We’d been alone with one another before, but never for two consecutive weeks. We went from Corsica to Italy to Switzerland to Germany, learning what it was like to live happily together as adults. The trip confirmed what we already suspected: ours was a lifelong love—a love that would transcend distance, time, petty disagreements, and any relationship turmoil.

As our college careers came to an end, we were faced with the opportunity to finally live together in the same city on a permanent basis. The only question was, where would we settle? After four years in Southern California, Liz was loath to leave the place, and she took a position with a small consulting firm in downtown Los Angeles. I decided that I wasn’t ready to enter the working world quite yet and accepted a generous offer from a graduate school in Chicago, setting out to work toward a PhD in sociology.

These decisions forced us to renew our promise to not let the distance come between us. Against all odds, we had made it work for the past four years—what was a few more? Besides, thanks to her entrance into the real world of working adulthood, Liz would now be making enough money to fly me to Los Angeles more often, or herself to Chicago. Still, we were confident our relationship would last.

Some people would meet Liz and assume that she was all beauty and no brains, but nothing was further from the truth. With her job after college, she turned her sights on becoming a high-powered management consultant. She traveled the country dressed in business suits and high heels, meeting with executives from some of the largest domestic financial institutions. Within seconds of shaking their hands, she’d have them enchanted by her intelligence, poise, humor, and wit. She could astound you with her explanation of some esoteric economic theory, but she also studied the pages of

US Weekly

and

People

magazine and could tell you all about this season’s hottest clothing trends and which celebrity was sleeping with his nanny. But whether she had met you an hour earlier or you had been lifelong pals, she was your friend.

Her smile invited people into her life, and her laughter made them stay. But if you deserved it, if you crossed a line and patronized her because of her size or the fact that she was a blonde woman, she could be tough. She once told an older male colleague who patted her on the head to fuck off. When we met someone new at a party and they asked what her job was, I would pipe in: “She fires low-level employees in order to raise stock prices by five cents for multi-billion-dollar banks and insurance companies.” Always quick to correct me, she’d say, “I don’t actually fire anyone. I recommend head-count reductions and leave the firing of employees to someone else.” Four years at an all-women’s college and her time as a management consultant only intensified the spitfire attitude she’d been cultivating since birth.

I loved her for that.

After two years, Liz and I independently came to the same obvious decision: it was time to live in the same city. Though used to the distance, we no longer wanted to deal with it. When I called her one night and told her about my realization, we agreed that I would to move to Los Angeles as soon as I finished up my classes and passed my master’s exam—the PhD was put on hold.

I graduated at the end of January 2002, and less than a month later my things were packed and I was on a cross-country road trip to Los Angeles, set to move in with Liz. I arrived on her front step with a newly purchased, prized possession.

“What is that?” Liz said.

“It’s an original drawing by Wesley Willis. It’s the shoreline of Chicago and Wrigley Field.”

“Well, it’s not coming in the house.”

“What? Why not?”

“Because it’s huge and ugly. Wait. When did you buy that thing?”

I thought about lying, but I knew she’d see right through it, so I felt compelled to tell her the truth. “Uh, last week, just before I left Chicago. I wanted something to remind me of the city and I thought this was perfect.”

Shaking her head, Liz asked, “How much did you pay for it?”

She knew that I had about three dollars in my bank account and a total of sixty-seven dollars of credit left on my Visa, because she’d had to pay for my U-Haul trailer and other moving supplies. Though I’d just told the truth, I used this opportunity for a little lie that I figured would keep me out of trouble. She was pissed that I’d bought this ugly-ass drawing, and she would have been even angrier if she knew how much I’d really paid for it.

“Uh, twenty dollars.”

“You paid twenty dollars for a shitty ink drawing on a giant piece of tagboard? What the hell were you thinking?”

I have no idea why I lied. I mean, the thing actually cost me fifty dollars, so a thirty-dollar lie wasn’t going to make a difference. What I didn’t realize then was that the cost of the thing didn’t really matter. It was the fact that I’d spent money when I didn’t have any to spend, at a time when we were preparing to start our adult lives together as a couple. I was still living in the fantasy world of graduate school, where student loans were used for records and beer. I had no idea what it was like to be a financially responsible, unselfish adult.

My philosophy around that time was perfectly summed up by a T-shirt I saw on a homeless man on the street outside of our apartment during my first week in Los Angeles: The Working Man’s a Sucker. I didn’t have a car, so I’d drop Liz off downtown each morning to make some money for us, then I’d pick her up later that evening. Every day, her first question was “Did you find any interesting jobs today?” I had a new excuse each time, but I didn’t really need to tell her what she already knew: I spent my first few months in Los Angeles actively trying to not be the sucker mentioned on that shirt by hanging out with my other unemployed friends and attending tapings of

The Price Is Right

.

In June of that year, after more than a few arguments about my motivation level, and a little over three months after my daily fake job search began, one of Liz’s friends recommended me for a job at an Internet company in Pasadena. I interviewed, and in their desperation to get a warm body in front of a computer screen, they offered me the job. My grandmother was appalled when she learned I went to work in shorts and flip-flops, spent most of the week playing foosball, and that Friday afternoons were dedicated to drinking beer at my desk. If only she’d known that I was writing ads for breast enhancement supplements and penis enlargement pills…

There was no real hope of advancement at my job. It was an hourly position, and I sort of just showed up and found novel ways to occupy my time until I could clock out for the day, earning salary increases that barely kept up with yearly cost-of-living adjustments. I didn’t hate what I was doing, but I didn’t love it.

Meanwhile, Liz moved up at her company, gaining titles and invaluable experience, and making more and more money. She also spent a significant amount of time traveling on consulting assignments. Though we finally lived together, months would go by when we’d see each other only on the weekends. For many couples, this extreme amount of time apart would be a real blow to the relationship, but for us it was just par for the course. It actually made the transition to living together a lot easier—if Liz had been home full-time, she would have immediately realized just how much of a lazy slob I was and probably would have kicked me out.