Two Tales: Betrothed & Edo and Enam (2 page)

Read Two Tales: Betrothed & Edo and Enam Online

Authors: S. Y. Agnon

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Literary, #Literary Fiction, #World Literature, #Jewish

In all cases, whether Band is correct about the degree of enigma enveloping “Edo and Enam”, we the readers still need to get at the elusive essential meaning of the story, which is set in Jerusalem of the final years of the British Mandate. The nameless narrator is house-sitting for the Greifenbachs, who have left behind their tenant Dr. Ginat, usually engrossed in his philological academic work or away conducting his research on the lost language of Edo and the Enamite Hymns. The itinerant manuscript merchant, Gamzu, is married to an exotic woman Gemulah, whom he had brought back to Jerusalem from her distant home among the lost tribe of Gad, where Ginat’s mysterious languages and hymns are still spoken and sung. It is this removal from her source that leads to Gemulah’s strange sickness. If it is a reunion that sets the plot of “Betrothed” in motion, here it is severance (of person from place, Gemulah from Gad; person from person, Gemulah from both Ginat and from Gamzu) which drives the events to their tragic end. (Through the good graces of the garrulous game of gutteral

gimmel

-words the reader should have a sense of the alliterative word-play Agnon is up to in this story.) It is the triangle of Gemulah-Ginat-Gamzu which becomes the focus of the tale, most of which is told through narrative conversation. If produced for the stage, the drama would look a lot like a drawing room play, set within Greifenbach’s book-lined study. We the audience would hear of the recluse Ginat and then hear the tormented Gamzu tell the tale of Gemulah. But no Noël Coward play would this be! There is nothing droll going on in Greifenbach’s drawing room, aside perhaps from Gerda’s speculation that Ginat has magically created a women for himself up in his room. More than she could know, that, too, turns out to be more tragic than comedic, as the final scene shifts out of the drawing room and up to the rooftop.

Baruch Kurzweil identified connections between “Edo and Enam” and Agnon’s

Sefer HaMa’asim

story cycle, and its dreamlike or nightmarish surrealism. If “Betrothed” can be read as Agnon’s modern midrash on Song of Songs, Kurzweil is correct in identifying “Edo and Enam” as his take on Ecclesiastes – with its focus on themes of eros and death.

Finally, when we describe these

Two Tales

as exemplars of Agnon’s modern stories, we mean set in the “new world” of revived Jewish life in the Land of Israel, not the

Yishuv HaYashan

of Jerusalem of old, nor Galicia of Reb Yudel in

The Bridal Canopy

. But they are modern in a more essential way as well. In the end, Jacob, like so many of the Jews of the Second

Aliya

, departs for America; Gemulah – in a story that portrays tensions between source and destiny (Meshulam Tochner’s hermeneutical explanation of the title) cannot survive in the new Jerusalem when taken out of her native element. These stories, authored shortly before and immediately after the establishment of the State of Israel, raise very “modern” questions about Jewish life, and like so much of Agnon’s writing, explore the connection and disconnection between “what was and what is”, “tradition and modernity”, “there and here” – and the degree to which the two sides of each of these dyads can be bridged, if at all.

Jeffrey Saks

Editor, The S.Y. Agnon Library

The

Toby Press

Tisha B’Av 5774 (Agnon’s 126

th

birthday)

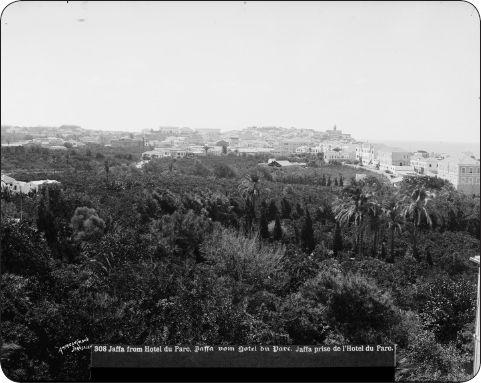

Jaffa view from Hôtel du Parc.

I

JAFFA IS THE DARLING OF THE WATERS: THE WAVES

of the Great Sea kiss her shores, a blue sky is her daily cover, she brims with every kind of people, Jews and Ishmaelites and Christians, busy at trade, at shipping and labor. But there are others in Jaffa who take no part in any of these: teachers, for instance, and such a one was Jacob Rechnitz, something of whose story we are about to tell.

When Jacob Rechnitz had completed his term of study and been crowned with a doctorate, he joined a group of travelers going up to the Holy Land. He saw the land and it was good, and those that dwelt within it, they were tranquil and serene. And he said to himself, If only I could earn my bread here, I should settle in this land. Jaffa was his dearest love, for she lay at the lips of the sea, and Rechnitz had always devoted himself to all that grows in the sea. He happened to visit a school, and that school needed a teacher of Latin and German. The authorities saw him, deliberated on him; they offered him a post as teacher, and he accepted.

Now Rechnitz was a botanist by profession and expert in the natural sciences. But as the natural sciences were already in the hands of another teacher, while the post of Latin and German was vacant, it was this post that was assigned him. For sometimes it is not the position that makes the man, but the man who makes the position, though it must also be said that Rechnitz was a suitable choice.

So Rechnitz set to work. He met his duties faithfully. He chose the right books and did not weigh his students down with tedious topics. He was never bitter with his students; never too proud with his fellow teachers, most of whom were self-taught. His students loved him, his colleagues accepted him. His students, because he treated them as friends; his colleagues, because he allowed them to treat

him

as one. And, too, his tall bearing and deep voice, his manners and his chestnut eyes that looked with affection on everyone, gained him the love of all. Not more than a month or two had passed before he had won a good name in the town. Not more than a month or two before he had become a favorite guest of fathers whose daughters had come to know him before the fathers themselves.

The fever of land speculation had already passed. The money-chasers, who had sought to profit from the soil of Israel, had gone bankrupt and cleared out. Jaffa now belonged to those who knew that this land is unlike all others; she yields herself only to those honest workers who labor with her. Some engaged in trade and some in the skills of which the land had need; others lived on the funds they had brought from abroad. Nor one nor the other asked too much of life. They left the Turk to his seat of power and sought protection in the shade of the foreign consulates, which looked on them more kindly than had the lands of their birth. The dreamers awoke from their dreams, and men of deeds began to dream dreams of a spiritual center and a land of Israel belonging to Israel. From time to time they would gather and argue about the country and its community, and send reports of their proceedings to the Council of the Lovers of Zion in Odessa. And all the while, each man was father to his sons and daughters, and husband to his wife, and friend to his friends.

Life was unexacting, very little happened. The days slipped by quietly, people were undemanding. Their needs were limited and easily satisfied. The well-to-do were content to live in small dwellings, to wear simple clothes and to eat modestly. A man would rise early in the morning, drink his glass of tea and take a few olives or some vegetables with his bread, work until lunch time and come home before dusk. By then the samovar was steaming, neighbors paid calls, tea and preserves were handed round. If some learned man were present, he would make fun of the hotel-keeper who had misunderstood a Talmudic word, and called fruit preserves “jam.” Or if a farmer were in the company, his conversation would be about the uprooting of vines and the planting of almonds, about officials and bribes. Or if a visitor from Jerusalem happened to be there, he would tell them what was going on in the City: if he were a cheerful type, he might amuse the company with a Jerusalem joke. If there were only local Jaffa folk present, they would discuss the news from abroad, even though it was already stale by the time the foreign newspapers arrived.

Jacob Rechnitz was welcome and warmly received in every house. He appreciated people’s efforts to speak German for his benefit, and pleased them in return with the smattering of Russian he had picked up. (Russian and Yiddish were still used rather than Hebrew; as for Rechnitz, he came from central Europe, where German was the common tongue.) Like most bachelors, he was glad to be brought into company; he fell in with his hosts’ ways of thinking so completely that it seemed to him that their views were indeed his own. Every now and then he would be invited to an evening meal; and afterwards, when the head of the family settled down to reading the latest journal, whether it was

Hashilo’ah

in Hebrew or

Razsvyet

in Russian, he would take a stroll with the daughters of the house. There was always light for such walks: if there were no moon, the stars would be shining; and if there were no stars, the girls’ eyes did well enough. Another young man would ask for no more than such a life; but as for Rechnitz, another world lay in his heart: love of the sea and of research into her plants. Even at the season when Jaffa’s hot air saps the marrow and the spirit of most men, he remained vigorous. From this same sea that brought profit to shipowners, carried vessels weighted with wares for merchants and yielded up fish for the fishermen; from these waters, Jacob Rechnitz drew forth his plants. Under the sea’s surface he had already discovered certain kinds of vegetation that no scientist had ever seen. He had written about them to his professor; and his professor, glad to have a capable scholar stationed in such a region, had published his reports in the Vienna periodical brought out by the Imperial and Royal Society for Botanical and Zoological Studies. Besides this, he urged his favorite pupil to persevere in his research, since no investigation into the marine plants off that coast had been undertaken so far.

Rechnitz needed no urging. He belonged to the sea as a bay belongs to its shore. Each day he would go out to take whatever the sea offered him; and if the hour was right, he would hire a fishing boat. Yehia, the Yemenite Jew who served as the school’s caretaker, would haggle for him with the Arab fishermen; and off he would sail to where, as he told himself, the earliest ancestors of man had had their dwelling. Plying his net and his iron implements, drawing up specimens of seaweed not found along the beach, his heart beat like a hunter’s at the chase. Rechnitz was never seasick; no, these mysteries beneath the waters, these marvels of creation, gave him fortitude. There they grew like gardens, like thickets, like shadowed woods among the waters, their appearance varying from the yellow of sulphur to Tyrian purple to flesh tints; they were like clear pearls, like olives, like coral, like a peacock’s feathers, clinging to the reefs and the jutting rocks. “My orchard, my vineyard,” he would say lovingly. And when he came back from the sea, he would wash his specimens in fresh water, which removes the salt that puffs them out, before laying them in a flat dish. (Anyone watching him might suppose that he was preparing a salad for himself, but he would forget his food for the sake of his plants.) Then he would take them from the dish and spread them out on sheets of thick paper; their slime was enough to make them adhere. Only a few of the world’s botanists are concerned with marine plants, and of these few Rechnitz alone was at work on the seaweed off the coast of the Land of Israel, investigating its qualities and means of growth and reproduction. Most scientists can only conduct marine research intermittently, on days when they are free from university duties; but Rechnitz was out every day of the year, in sunshine and rain, by day or by night, when the sea was warmed by the sun and when it was cold, in calm or storm, when other folk slept or when they were busy with their affairs. Had his concern been with the study and classification of plants on dry land, he would have become a celebrity, been made a member of learned societies and spent his time at discussions, meetings and conferences. But since his activities were in a sphere remote from the interests of the Jewish settlement, his name was unknown in the land and his time was his own. He carried on with his investigations and collected many plants. If he found a specimen he could not identify, he would send it abroad, hoping his teachers might know more about it. So it came about that they named a certain seaweed after him, the

Caulerpa Rechnitzia.

It was not long before he was invited to contribute an account of the larger seaweeds for Professor Horst’s famous work

Cryptogams of the Mediterranean.

II

This is how Rechnitz’s interest in his field began. When he first entered the university he chose no special subject but applied himself to all the sciences, and particularly the natural sciences, for these had drawn his heart. He already thought of himself as an eternal student, one who would never leave the walls of the academy. But one night he was reading Homer. He heard a voice like the voice of the waves, though he had never yet set eyes on the sea. He shut his book and raised his ears to listen. And the voice exploded, leaping like the sound of many waters. He stood up and looked outside. The moon hung in the middle air, between the clouds and stars; the earth was still. He went back to his book and read. Again he heard the same voice. He put down the book and lay on his bed. The voices died away, but that sea whose call he had heard spread itself out before him, endlessly, while the moon hovered over the face of the waters, cool and sweet and terrible. Next day Rechnitz felt as lost as a man whom the waves have cast up on a desolate island, and so it was for all the days that followed. He began to study less and read books about sea voyages; and all that he read only added to his longing, he might as well have drunk seawater to relieve a thirst. The next step was to cast about for a profession connected with the sea: he took up medicine, with the idea of becoming a ship’s doctor. But as soon as he entered the anatomy hall he fainted; he knew then that this could never be his calling. Once, however, Rechnitz happened to visit a friend who was doing research on seaweed. This man, who had just come back from a voyage, showed him the specimens he had brought. Rechnitz saw and was amazed at how much grows in the sea and how little we know about it all. He had scarcely parted from his friend before he realized what he was seeking.