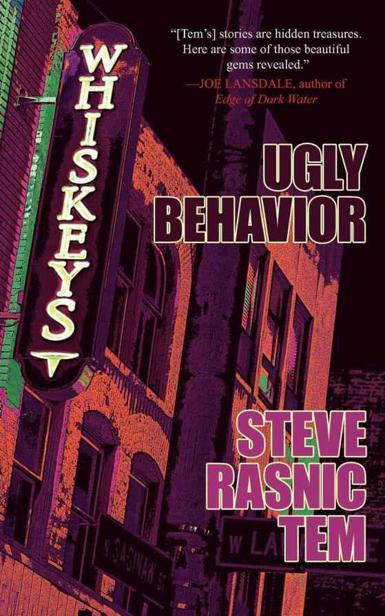

Ugly Behavior

Authors: Steve Rasnic Tem

Ugly Behavior

Steve

Rasnic

Tem

2 PM: The Real Estate Agent Arrives

Introduction

I’m not particularly known as a writer of violent stories. But

ugly stories, tales about the terrible things we do to ourselves and to each

other, have always accounted for a portion of my work. (And of course there are

those who believe all tales of crime and horror—whether supernatural or

not—are by definition “ugly” and do not care to read about these things.

A collection such as

Ugly Behavior

would not be for them.) Both for those readers who appreciate this sort of thing,

and for readers who would prefer not to encounter this other mode of mine, I’ve

put all these ugly stories together into one box. It’s that box under your bed,

pushed all the way back against the wall, the one that takes some effort to get

to, the one your momma doesn’t know about (or at least, the one you like to

think she doesn’t know about).

As ubiquitous as that age-old reader’s question, “Where do you get

your ideas?” is that question specifically put to crime and horror writers,

“Why do you want to write of such things?” or perhaps more to the point, “Why

would you want to tell such an ugly story?”

In my case people often say, “But you look so peaceful… you seem

so optimistic.” People see this as a contradiction. In truth, I am an optimist.

I believe wonderful things can come out of the most terrible events. I also

believe life is hard enough for most people and we have no business making it

even harder if that can be avoided. I believe we have a duty to each other to

be as kind as possible. And I want my kids and grandkids to surround themselves

with good and kind people.

I also believe the world is full of predators and the vilest kinds

of monsters. People are capable of the ugliest behavior. For me, to ignore

these things is to ignore the deadly snake in the room. We need to know what

we’re up against, so that we can really appreciate what it means to “behave

honorably.”

The other thing that sets these stories apart from the majority of

my work is that no fantasy elements are involved. The terrors here are the

daylight terrors of human interaction.

At times transcendence and transgression appear to be unexpectedly

close neighbors. Most of us, I think, crave some sort of transcendence. We want

to move from where we are in our lives to a better place. But when we cannot

achieve that, some of us will choose transgression. Of course sometimes

transgressing societal norms may be the only way to achieve some kind of social

evolution. But we cannot always tell the difference between that positive

action and its destructive counterpart. We become so eager to escape the limits

of everyday life we are just satisfied that there’s been any kind of movement

at all.

—Steve

Rasnic

Tem, 2010

In the backyard, after the family moved away: blue chipped food

bowl, worn-out dog collar, torn little boy shorts, Dinosaur T-shirt,

rope, rusty can, child’s mask lined with sand. In the corner the

faint outline of a grave, dog leash lying like half a set of parentheses.

Then you remember. The family had no pets.

My father used to say he loved the southwest because here it’s

obviously the landscape that matters and not the people. People who try to

compete with their buildings, their roads, and their works are all just too

pitiable, as if they were desperate for God’s attention. “In the process they

came damn near to ruining this country,” he’d say. “I mean, look at Phoenix.”

Never mind that I liked Phoenix; both as child and daughter my opinion on the

matter didn’t count. If my brother had lived past the age of six his opinion

might have had more weight, but I honestly doubt it, even though I’ve held onto

the notion now and then as a convenient source of resentment.

Once or twice a year my father would drive me up to the Grand

Canyon just to put me in touch with something “beyond man’s power to alter.” To

me the Canyon was just this great big hole in the ground, but I knew better

than to say that to my dad. Dad said he was glad he was a painter and not an

architect in the face of such awe-inspiring vistas. This landscape, he said,

required an artist already in sympathy with that world where human concerns

were irrelevant.

My father was the

perfect artist for that landscape. He had a “problem” with human beings, was

the way he put it. Not a fear, exactly, but an obvious unease. Not exactly a

hatred, or at least not a hatred he would admit to, but a profound distrust. If

you look closely at his most famous painting, “Saguaro Night,” you can see

signs. Row after row of blackened saguaro lean forward as if marching toward a

distant wrinkle of mountains. The sky behind and above all this is deep, inky,

unfathomable. The painting seems simple enough at first glance, but then you

start thinking why are the cacti so black? Has there been a fire? I always

thought they looked as if they were suffering. Maybe they’re not cacti after

all? My father didn’t paint them realistically, exactly, but in a style he

called tormented expressionism. The lines are tortured, the shapes distressed,

the colors despairing. No one really “likes” the painting, although it has

fetched incredible prices over the last few years. I’ve heard that the last two

owners couldn’t bear to hang it in their homes. I’m told that once an old

woman, a concentration camp survivor, burst into tears upon seeing it in a

traveling exhibition of my father’s work.

One cactus is not black—that small one in the background, on

the edge of the right upper quadrant, a shimmering red-orange laid in with a

few quick strokes, hardly formed, really. But so compelling. Some people say

that’s where the other cacti are leaning toward, their cactus deity. I’m not so

sure about that, but I do know that’s where the eye goes.

So my father’s primary artistic inspiration was a distrust of

human beings. Like any good daughter, I became his opposite. My weakness as an

artist, and as a human being, is that I’ve trusted and loved people too much.

My paintings, and my relationships, have been overwrought, sentimentalized,

unrealistic affairs. Critics have pointed out superficial resemblances in our

work, always to my detriment. Certainly I learned my technique from him, but

I’ve always taken it too far—I lack his iron discipline. And we’re both

attracted, at least initially, to drunks and addicts. But after a year or so of

passionate involvement, my father always leaves his unfortunate choices behind.

He was with my mother a record two years, two months. I usually stay with my

lovers until they ruin me.

And yet, strangely enough, for all this I always knew that my

father both appreciated and loved me. I was always the only one.

My father had lived by himself on a small ranch outside Tucson for

over twenty years when I came to stay with him the last few years of his life.

I was running from yet another bad relationship. I suppose because this one had

been so particularly bad, I ran to my father. Dad’s relationships, also, had

always been spectacularly bad. But he survived them, even thrived on these

dramatic break-ups. He always appeared more content afterwards, and his

paintings only improved. I decided this was yet another area where I could

learn from his technique.

“So this young man, do you suppose he’ll be following you here?”

“God, I hope not.”

“There is no god, sweetheart,” he corrected me quietly, matter-of-factly,

as had always been his way. I had been watching him paint—he didn’t mind;

he said he’d just pretend I was yet another saguaro cactus—and I wondered

at what he was working on. All his paintings those last few years started the

same—he painted the blacks first, the endless sky, the mirroring ground.

Much later more specific objects would appear, as if he’d shone a flashlight on

them, or rubbed the night away just enough to reveal them. The beginning he

made that day would evolve into the painting which became known as “Saguaro

Night.”

“Sometimes I forget, Daddy.” He didn’t say anything, but I could

see his cheeks lifting slightly. I knew he was smiling, just a little. He was

very lean, and the first signs of his illness were just beginning to show. His

muscles moved with no secrecy beneath his skin.

“When you were little you asked me to paint a picture of God for

you,” he said. “I suppose if I stopped this painting right about now…” He added

another brush of darkness to the canvas. “I guess I’d just about have him.”

On impulse I hugged him from behind. I shocked

myself—usually I didn’t dare touch him while he was working—but he

didn’t pull away, and I didn’t feel him stiffen at all. He just kept adding

more of that endless night sky to the painting.

The summer was passing uneventfully. The days were beyond hot, and

although he kept several ancient fans around, he refused to have anything to do

with air conditioning. I didn’t paint anything, even though he had set aside

studio space for me in an annex to his own work room. I could feel his intense

disapproval, but he never said anything. I couldn’t imagine working in such

heat, worse than anything I’ve ever experienced, but he was at it eight hours a

day, seven days a week. After dusk he would fix us both some dinner—he

never permitted me to cook—and afterwards he would sit in a rotting old

chair on the edge of the desert twenty or so yards from the house, just

watching the night sky that existed, I think, both outside and inside his head.

He wasn’t exactly unfriendly about it—he often invited me to join him,

but I always declined. This was his, and besides, there was only one chair out

there.

We never saw anyone except for a couple of old cowboys who came by

now and then to do repairs to the house or the fences, and the boy from the

local grocery in his battered green pickup. Each time I’d open the door to let

the boy in with the supplies I’d be amazed at how wet he was, and how he seemed

just a bit smaller than the last time, as if his brown skin were shrinking

around him like the sheath over a fried sausage link. I stayed inside on days

like that—the newspapers the grocery boy brought each time (just for me,

of course), talked about windshields on parked cars exploding from the heat. I

wrote lots of letters during that summer to old friends and boyfriends, but I

didn’t mail any of them. The letters were all alike, and like my father’s

paintings: all about the heat and the sky, and the dark that came without

street lamps to lighten it.

But sometimes I’d start writing about the dark and the sky, and

something from the newspaper would slip into the letter, almost without my

noticing it. I suppose that shouldn’t have been too surprising, since all there

was to write about was the dark, the heat, and the sky, and whatever I read in

the newspaper.

A lot of terrible things happened that summer, according to the

papers (I had no reason to doubt them, but I’d never felt so isolated from

other people’s news as I did then so it was a little like reading about these

events in a novel). Four girls, ten to eighteen, had been raped, strangled, and

left out in the desert where the animals found them before their families did.

A father had locked himself in the house with his three kids and then set fire

to the place, while the mother sat wailing and screaming helplessly outside. A

shoplifter had been chased from a downtown store where three cowboys caught

him, beat him, then threw him out in front of a moving truck. The usual run of

traffic accidents, bad enough in and of themselves, but then there was that

especially hot Wednesday afternoon that a long distance truck driver “went

strange” and plowed down the highway hitting everything and everyone he could.

The final death toll on that one was twenty-eight, with a dozen more

permanently disabled.