Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (32 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

Sports in the City

Griffith Stadium

2041 Georgia Ave.

Most of the baseball history that D.C boasts belongs to the little ballpark that wanted to be a stadium, once located at Georgia Avenue. Griffith Stadium was the home of the original Washington Senators from 1911 through 1960 and the second incarnation of the Senators in 1961. It was also the home of the Negro Leagues’ Homestead Grays from 1937 through 1948, Washington Elite Giants from 1936 through 1937, Washington Black Senators in 1938, Washington Potomacs in 1924, and Washington Pilots in 1932. Even the NFL’s Washington Redskins called Griffith Stadium home from 1937 through 1960.

In essence, Griffith Stadium represented far more than simply a place where sporting events took place. It was a cultural touchstone for D.C., that also held concerts, lectures, and many other important events. Though its former grounds are now part of the Howard University Hospital campus, a plaque where the park once stood can be found on Georgia Avenue.

With just half a set of choppers on both the top and the bottom jaws (different sides) Announcer Wannabe Guy can often be found standing on his seat located below the Shirley Povich Media Center in the upper deck, holding a frayed program in hand, and shouting out his extended and improvised starting lineups and game calls at the top of his lungs. You have your bad self a good time, Announcer Wannabe Guy!

We Felt Blessed to be on the Road Again

Washington, D.C., was the first stop on our second tour of all the ballparks in the bigs. Schedules had been consulted, plans had been made, and the trip had commenced. Kevin had driven from his home in Pittsburgh and picked up Josh from his flight out of Portland, Maine. And just like that, the second baseball adventure of a lifetime had begun.

“I can’t believe we get to do this again,” Josh said, pulling his ball cap down low.

“We were lucky to be able to do it one time,” Kevin added. “Twice is ridiculous.”

And while this was true, things had changed a bit since our first hardball odyssey. We were a bit older, we had jobs and families and

real

lives now. Our lives were full of people and responsibilities that we needed to pull ourselves from to make the trip happen.

We passed through the sites of the great city—Georgetown, the Pentagon, the Washington Monument, and the Capitol building—but our hearts really started pounding when we entered the Navy Yard neighborhood. With all due respect to the great buildings and sites of our nation’s capital city, there is nothing like experiencing a new ballpark for the first time. The green of the grass, the brown of the dirt, the smell of the hot dogs and crack of the bat just seem to ring a little truer than usual. And we had nothing to do the next day but head to a new city and do it all again. Ah, heaven.

At that point Josh turned on the air conditioning.

“What are you doing?” Kevin asked.

“It’s 95 degrees out. I’m going for some AC,” Josh replied.

“Yeah, but I’m the driver,” Kevin argued. “The driver decides between AC and windows.”

Josh shook his head. “Didn’t we go over all this on the first trip?” he said. “Driver gets to decide music and cruising speed. Passenger navigates and gets control over in-car environment.”

“Yeah,” said Kevin, “It’s all coming back to me.”

Maybe it was the heat, or maybe the traffic, but we’d already started to agitate one another. Josh was trying to hold back but his frustration could not be contained.

“Do you have to keep doing that?” he finally snapped.

“Doing what?”

“Lunging the car forward, then braking to avoid hitting the car in front of us,” Josh said.

“Dude, they call it stop-and-go traffic for a reason.”

“You know I hate being called dude, dude?”

“Chill out before I leave you at the side of the road like a busted tire.”

We arrived at the ballpark early and after some more pleasant driving around, managed to find a place to park for a few hours without paying. We both readied our ballpark road tripping essentials: wallet, camera bag, and voice recorders for taking notes. It was then that Kevin noticed something strange.

“What the hell is that?” he asked Josh.

“My tape recorder,” Josh replied. “It’s the same one I used on our first trip.”

“Are you really that cheap?” Kevin chuckled. “Ever hear of an MP3 recorder?”

“Cheap has nothing to do with it,” Josh defended. “The quality of analog is much better.”

“You’re not recording the Beatles on the roof of Apple Studios, you moron. It’s the sound of your own stupid voice. How good does it need to be?”

“Well, I like it,” said Josh. “I have a good voice and it suits me.”

“It suits you?” said Kevin. “How many tapes did you bring for the trip?”

“A dozen. Why? How many MP3s can you make?”

“As many as I want,” Kevin said. “I have more than 400 hours of recording time with no need for those ridiculous little tapes. I’m surprised they even still sell those.”

“Good thing,” Josh laughed. “You were always losing your tapes anyway.”

“Haven’t lost your lame sense of humor either, I see,” Kevin said.

“And I’ll bet you still refuse to stop for directions when you’re lost,” Josh chuckled.

“As any self-respecting man would,” Kevin protested. “You still listening to that God-awful Kenny G?”

“No,” said Josh. “I mean, I never did.”

“You did. Constantly.”

“I never listened to Kenny G,” said Josh.

“Whatever,” chortled Kevin.

“Whatever yourself. It’s just … sometimes I find that music soothing and when I spend time with you … well, I tend to

need

a little soothing.”

“Starting to wonder if this trip was a good idea?” Kevin asked.

“You said it, pal.”

And as we approached the outside of Nationals Park and began to take it all in, we were comforted by the thought that for everything that had changed over the years since we first hit the road together—wives (well, one each), children, mortgages, day jobs, and all the ways that we mark time moving forward in our lives—it was good to know we would still annoy the heck out of each other, just as we always had. One thing was for sure: Our second trip around the bigs was going to be just as much fun as the first.

BALTIMORE ORIOLES,

BALTIMORE ORIOLES,ORIOLE PARK AT CAMDEN YARDS

The Ballpark That Changed Everything

B

ALTIMORE

, M

ARYLAND

40 MILES TO WASHINGTON

105 MILES TO PHILADELPHIA

190 MILES TO NEW YORK CITY

245 MILES TO PITTSBURGH

W

hen Oriole Park at Camden Yards opened in 1992, it signaled the renaissance of the American ballpark, and provided teams across the land with a blueprint for the future. A year prior, the White Sox had unveiled sterile U.S. Cellular Field, and before that the most recent additions to the big league landscape had been Rogers Centre (1989), the Metrodome (1982), the Kingdome (1977), and Olympic Stadium (1977). Notice a trend? For more than a decade, stadium designers had somehow fallen under the misimpression that fans favored arena baseball to the real thing. To put things in perspective, that’s as egregious a mistake as assuming Americans like Wiffle Ball better than real baseball. Yes, Wiffle Ball may boast more adult participants each year than actual hardball, but that’s a statistic born of necessity not our true preferences. The cold, hard reality is that most of us don’t have seventeen able-bodied friends on hand to field the two teams needed for “real” baseball whenever the spirit moves us to take a few hacks and toss a few curveballs. So we settle for as close an approximation of the “real” experience as time, able-bodied fielders, and the confines of our backyard will allow. That’s what all those fans filling the Metrodome, Kingdome, and Olympic Stadium were doing in the 1980s. What’s that, you say? The fans hardly ever filled those domes? Well then, you just made our point. Baseball had strayed from its pastoral roots before Camden Yards came along just in time. When baseball needed a throwback to remind owners, fans, and players of its glory days, Camden provided one and in so doing restored the notion that the ballpark could and should be a magical place.

The park was a hit from the very start. The O’s immediately boosted nightly attendance from the thirty thousand per game they had been attracting at Memorial Stadium to forty-five thousand. This led other teams and their owners to begin new stadium projects of their own or to infuse ones that were already on the drawing board with modifications meant to replicate Camden’s finer points. There was one not-so-tiny bump along the game’s road to recovery, though. Two years after Camden Yards opened, the owners canceled the 1994 World Series and many fans swore they’d never come back. In some cities, like Montreal and Toronto, they were true to their word. But as new ballparks opened throughout the latter half of the 1990s and early 2000s, most fans found it in their hearts to forgive the game its imperfections and showed up in droves at the new yards. Sure, all of those steroid-propelled home runs had something to do with the game’s comeback, and the fanfare surrounding Cal Ripken’s amazing streak did too, but the retro ballparks—all inspired by Camden in some way—were at the heart of the reawakening.

Without Camden, we can imagine a league unable to rebound from the atrocity of 1994. We imagine team owners and cities still enthralled with their four-tiered, multi-functional, peripheral-revenue-generating, cookie-cutter stadiums and domes. Across the league we see misguided ladies and gents, each boasting of their facility’s capability of hosting a bass fishing expo in the morning, a baseball game at night, a monster truck rally the next day, and a football game on Sunday. We see fans staying home, unmotivated to embark on hardball odysseys. We see an empty place on the bookshelf where

The Ultimate Baseball Road Trip

ought to be.

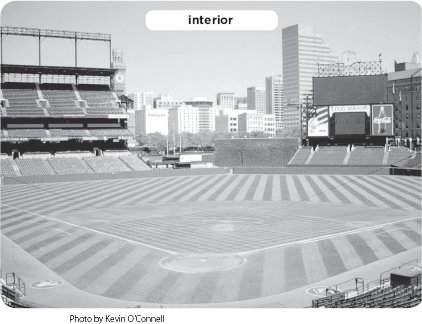

But thankfully Camden did come along. And today, with the benefit of hindsight, it is easy to see why it won a bevy of architectural awards upon its debut. It merges the charm of a classic old-time ballyard with the comfort and convenience made possible by modernity. That was its genius, which may not seem so revolutionary today, but was when it opened. In the shadows of the trademark B&O Warehouse, fans find a regal brick exterior that channels the quirks, eccentricities, and asymmetrical field dimensions of baseball’s classic era. But fans find inside the stadium, as well, nice wide aisles, spacious concourses, and great sight

lines. Not only did this park raise the bar for other MLB parks, but it did so smack dab in the middle of its city, paving the way for subsequent “urban renaissance” ballpark projects in places like Cleveland, Detroit, Pittsburgh, and Colorado.

Prior to Camden, cities built new ballparks only when their current digs started falling apart. And they built them on the outskirts of town or in the burbs where land was cheap and brand new freeway ramps could be commissioned to allow for easy-in, easy-out game-day “experiences.” After Camden, owners of structurally sound, still-functional facilities began building new and improved ballparks. And they built them downtown, where fans could turn a night at the ballpark into a

full

night in the ballpark neighborhood.

Most importantly, since Camden opened, the “cookie-cutter stadium”—as a generation of nondescript facilities would be ingloriously dubbed owing to its representative members having so few unique characteristics that it seemed as though all had been created from the same symmetrical cookie cutter or mold—has gone the way of the spitball. From Queens to St. Louis, Pittsburgh to Cincinnati, and San Diego to San Francisco, teams that once played in these multi-functional stadiums now have authentic baseball parks to call their own. Each reflects its city’s unique personality and celebrates the charm of the game’s olden days. Only the Oakland Coliseum stands out as a holdover from an era thankfully past, continuing to host the game in a stadium better suited for football.

Somewhat surprisingly, Oriole Park was designed by the same architectural firm that drafted up the prints for U.S. Cellular Field, a park that would need—and receive—several serious rounds of renovation less than a decade after its opening to bring it up to the new post-Camden par. And it still isn’t quite there. Thanks to the mulligan HOK took in Chicago and to the help it received in Baltimore from an architectural consultant named Janet Marie Smith (who would later become an HOK employee, then a Boston Red Sox employee, then an Orioles employee), HOK became the leading authority in ballpark construction. The firm, which is now known as Populous, has left its mark on yards major and minor across the country.

According to local lore, the Maryland Stadium Authority initially drafted plans for a multi-tiered stadium similar to U.S. Cellular, before Smith objected. She insisted on building a baseball-only facility that mimicked early 1900 parks like Ebbets Field, Shibe Park, and Fenway Park. Old-style features at Camden include an ivy-covered hitter’s backdrop in center field; a twenty-five-foot-high “mini-monster” in right; a low, open-aired press box; a sunroof atop the upper deck; steel-support tresses; attractive brick facades; an elegant main entranceway; and a festive plaza outside. More than that, the stadium’s orientation allowed fans in the grandstand to enjoy a sweeping view of the downtown skyline across the outfield. The highlight of this stellar view was the 288-foot-high Bromo-Seltzer tower, a Baltimore landmark that bears a face clock and ornate crown. Unfortunately, though, this charming outfield view became a victim of Camden’s success. Due to the urban revitalization the stadium prompted, a 757-room hotel popped up just north of the stadium footprint, as well as an apartment building. Since their completion in 2009, the sight lines beyond left-center haven’t been the same.

Josh:

I think I can still see the top of the tower if I stand on my seat.

Kevin:

Camden brought the neighborhood back to life. Then the neighborhood grew. Now Camden is diminished because of it.

Josh:

Say what?

Kevin:

There’s a lesson here. I just haven’t found it yet.

Josh:

Huh?

Kevin:

Why are you standing on your seat?

Camden was built for $110 million. In addition the land acquisition and preparation of the work site cost $100 million. This $210 million price tag seems paltry by today’s standards. For example, Citi Field and the new Yankee Stadium cost $850 million and $1.5 billion, respectively. Surely that’s due to two decades’ inflation and the high price of, well, everything, in New York, you may say. And to that, we reply, true, but even Minnesota’s Target Field cost $545 million. Camden was publically financed through a new instant lottery game that was approved by the Maryland legislature in 1987. All of the proceeds went toward the ballpark, which angered some Old Line State citizens who pointed out that the park was being funded by the poor, who typically play the lottery more often than well-to-do folks. This came after Maryland’s legislature had rejected previous attempts to use money from a new lottery game to improve education. When it came down to it, Maryland didn’t want to lose its baseball team the way it lost the Baltimore Colts in 1984. After the Colts left for Indianapolis in the dead of night, it took Charm City thirteen years to get back into the NFL. With the sting of that departure still festering in the local consciousness, it’s no surprise the O’s got a sweetheart stadium deal. And besides, there was no denying that Memorial Stadium had outlived its day. The multipurpose stadium, which had housed both the Orioles and Colts dating back to 1950, had accrued over the years such conspicuous nicknames as “The World’s Largest Outdoor Insane Asylum” and “The Old Gray Lady of 33rd Street.”

Kevin:

Hmm … sounds like it was time for a change.

Josh:

Can’t you just see folks standing at the water cooler: “What did you do on Sunday?” “I paid a visit to the Old Gray Lady of 33rd Street.” “I was at the Insane Asylum.”

Kevin:

Are you finished?

Josh:

I think so.

Renovations to the trademark B&O Warehouse that looms over right field took just as long to complete as the stadium construction: thirty-three months. The circa 1905 building is the longest free-standing structure on the East Coast at 1,016 feet, but it had fallen into disrepair by 1988. Nearly all of its 982 windows were broken and all eight floors were rat-infested. When workers started power-washing the brick exterior, the mortar began crumbling, so they had to clean the rest by hand, brick by brick. The building once served the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, which debuted as the first operational US rail in 1827. Today the B&O contains restaurants and shops on its lower levels and Orioles team offices upstairs. On its roof, it houses a bank of ballpark lights.

Josh:

I bet whoever built the B&O never would have guessed that one day there’d be all these glowing electric lights on its roof.

Kevin:

Or that the B&O would be the cheapest square in Monopoly.

For the ballpark’s rather lengthy name—Oriole Park at Camden Yards—we can thank two factions of state officials within the Maryland Stadium Authority. One group favored “Oriole Park,” the name of the baseball field used by Baltimore’s National League team of the 1890s, while the other preferred “Camden Yards,” in recognition of the neighborhood where the ballpark resides. And thus, in this city just forty miles from Washington, D.C., and the hallowed halls of Congress, a compromise was brokered. And then, after the ribbon-cutting ceremonies were over and the politicians had had their say, the people spoke. Fans began referring to the Orioles’ new digs as “Camden Yards,” so in common parlance that might as well be its name, even if its “official” title is lengthier.

The O’s christened Camden with a 2-0 win versus Cleveland on April 6, 1992, and went on to win ten of their first eleven contests that year, the best start in MLB history for a team opening a new park. Consider it redemption for the 1988 season when the O’s set the record for the most losses to open a season with an incredible 0-23 start.

Trivia Timeout

Egg:

After leaving the National League to join the fledgling American League in 1901, the early birds soon departed for what city?

Hatchling:

Which two former Orioles are among the four players in big league history to amass five hundred home runs and three thousand hits?

Big Bird:

Which player once hit a ball through one of the B&O Warehouse’s open windows?

Look for the answers in the text.