Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (72 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

Josh:

He’s a bird, obviously. He thought he could fly.

Kevin:

Looks more like a hippo.

Josh:

He sure dropped to the field like a hippo.

If you’re like us, you haven’t enjoyed fireworks on top of the garage since prom night. But at the Prog fireworks are shot from the top of the parking structure across Eagle Avenue that is attached to the ballpark. We saw the kind that shoot flaming colored rockets into the air and the cannon-fire-with-big-boom kind. The team fires them off after the end of the National Anthem, when the Indians hit a home run, and when the Indians win.

In 2011, the Indians introduced a new hospitality room for any fan who is blogging, tweeting or otherwise using social media to comment on the game. Fans can go to this comfy luxury box and have some quiet space to fire off their ideas into Cyber Space. For a blogger, we have to think this would be about as good as it could get. After all, they spend most of their time sitting in their bathrobes working out of home offices, right?

Josh:

It’s a brave new world, my friend.

Kevin:

Burgers with cheese on the inside in Minneapolis, and now this.

Josh:

Everything’s changing so fast.

Kevin:

We’re just getting old.

Major League

made this guy one of the most famous superfans in the bigs. Sitting atop the left-field bleachers, he beats the drum to inspire Indians rallies. He has an arrangement with the team that dictates when he is free to bang away. He only hits the drum when the Tribe has runners in scoring position and he always quits well before the pitcher delivers the ball. He sits in a nice shaded spot underneath the scoreboard with his wife. His name is John Adams and he began banging away at Municipal Stadium back in August 1973. He played his three thousandth straight game in 2011.

Josh:

Take that, Cal Ripken!

Kevin:

Yeah, this Iron Man never had to move to third base!

The 1949 season saw Indians fan Charley Lupica gain national fame. With the World Champion Tribe in lowly seventh place, Lupica climbed sixty feet in the air to a perch atop the flagpole above his Cleveland deli, vowing to remain there until the Indians either clinched the AL title or were eliminated from the pennant race. His vigil saw him atop the pole for 117 days, where he missed the birth of a child but garnered national newspaper and magazine coverage. Never missing a marketing opportunity, owner Bill Veeck sent a truck to transport Lupica—still sitting atop his flagpole—to Municipal Stadium on September 25, the day the Indians were officially eliminated from the pennant race. As Lupica finally descended, a crowd of thirty-four thousand was on hand to cheer him on. Don’t ask us how he went to the bathroom during his time in the clouds. You don’t want to know.

Kevin:

I don’t suppose either of those guys gives a hoot one way or the other today.

Josh:

Yeah, they’re probably pretty much decayed by now.

Kevin:

Um, I was thinking of them playing catch together in the afterlife.

Josh:

That’s a bit more romantic, I guess.

Cyber Super-Fans

- Let’s Go Tribe

We love the fan-confidence meter.

- Wahoo Blues

A good source for trade rumors.

- www.indiansconfidential.com/

A good site for game recaps and series previews.

We Ate “Dirty Water” Dogs

Finding ourselves unable to score any tickets to a playoff game while in Cleveland several years ago, we watched the game between the Indians and Mariners with our friend and Cleveland tour guide, Mr. Dave Hayden, Esq. As soon as we walked in the door of Dave’s apartment, he had a pot of hot dogs boiling and we settled in for what would prove to be a great series.

Sports in the City

League Park Site

666 Lexington Ave.

We recommend that visitors to Cleveland pay a visit to the grounds where Nap Lajoie played. League Park Center sits at the corner of Lexington and 66th, offering youth fields and a portion of old League Park’s facade. The actual ticket booths are intact in addition to a large stretch of the left-field exterior brick wall. The old ballpark almost takes shape as you look at these structures. There are efforts under way to restore the site, but the city should get on this one fast. It would be a shame to let it deteriorate any further. League Park is definitely worth a visit and a photo for anyone who is a fan of old ballparks.

Visiting League Park reminded us that it was the setting for one of the most disputed batting titles in history. In 1910 the Chalmers Automobile Company pledged to give one of its cars to the AL batting champ, and as the season wound down, it became clear that either Ty Cobb or Nap Lajoie would be driving home in style. Cobb skipped the last two games to protect the lead he enjoyed. Nap’s last two games came in a doubleheader against the St. Louis Browns, and he took full advantage, bunting six times for hits, and ending up going eight for nine on the day, his lone blemish being an error charged on a throw to first. The bunt hits proved enough to give him the lead over Cobb.

There was a problem, however. The reason Nap bunted so often was that a rookie named Red Corriden was playing a deep third for St. Louis. After the game, Corriden said his manager Jack O’Connor told him to play back, because one of Nap’s line drives might otherwise take his head off. O’Connor was a former Cleveland Spider and teammate of Lajoie. Also, it was reported that Browns coach Harry Howell tried to bribe the official scorer with a new suit, if he were to change the error to a hit, but the scorekeeper declined.

Cobb fans and Tiger president Frank Navin were furious when the next day’s papers declared Lajoie the winner. But not everyone in Detroit was upset. Eight of Cobb’s friendly Detroit teammates sent a telegram to Lajoie congratulating him on his victory. AL president Ban Johnson conducted an investigation into the events and determined that O’Connor and Howell had done nothing wrong, but soon after they were both removed from their positions, and were never involved with baseball again.

The Sporting News

settled the dispute when it listed the official averages as Cobb .3850687 to Lajoie’s .3840947. Cobb had won anyway. But Chalmers gave cars to both players.

But wait, there’s more. In the 1980s baseball historian Paul McFarlane discovered two hits with which Cobb had been incorrectly credited during the season, giving the posthumous title to Lajoie. But Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn did not revoke Cobb’s 1910 title, thus preserving his streak of nine consecutive AL crowns.

And hold on, there’s still a little more. Today’s definitive source for baseball stats—Baseball-reference.com—lists Lajoie as the winner at .384 and Cobb as the runner-up at .383.

First Dave brought out a few beers. What a great host. Next came the salted peanuts. We all shelled away and then noticed Dave do something odd. He just threw the shells down on the hardwood floor of his own apartment.

“What are you doing?” Josh asked.

“Oh, I like a

real

ballpark atmosphere here,” came Dave’s response, not taking his eyes off the television set. So with that, we dropped our handfuls of shells onto the ground, and tee-heed, looking at one another. We still weren’t sure if Dave was kidding.

Then Dave left the room to get the dogs, which smelled just about ready to us.

A moment later, Josh was applying ketchup and onions to his, while Kevin slathered on a healthy dose of Stadium Mustard. We all bit down into the dogs at the same moment. Ah, the joys of baseball.

But we both tasted something peculiar. Not wanting to appear ungrateful, neither of us commented at first. But there was an odd flavor, not quite in the dogs, but on them. We exchanged a confused look. After ingesting so many dogs in our years of baseball travels together we were pretty expert in the ways of the hot dog. But here was something new and not altogether pleasant we were encountering.

“Dave,” Kevin finally said, “What’s with these dogs? They taste … funky.”

“That’s because they’re ‘dirty water dogs,’” said Dave, smiling from ear to ear.

“Dirty water!” shrieked Josh. “The horror!” He spit a mouthful of hot dog, bun, and ketchup onto the floor.

Even Kevin was disconcerted by this revelation. His mind raced with all kinds of definitions of dirt: disease, pesticides, nuclear waste, scurvy.

“Of course,” said Dave calmly. “The Tribe won yesterday, so I couldn’t very well change the water. It would kill the mojo.”

“Is it sanitary?” asked Josh, a bit relieved his dog hadn’t been soaking in scurvy.

“Who gives a crap? You don’t mess with a streak,” said Dave. “The real question is, how do they taste.”

Kevin looked at Josh, who was looking somewhat regretfully at his discarded dog on the floor.

“How did you come up with this little, uh, tradition?” Kevin queried.

“I used to work the concession stand at Municipal,” said Dave, “and when it came to boiling dogs, we used the same water over and over until it couldn’t be used any more. Stalagmites of grease steam collected on the ceiling above the pots, dripping back down. Now whenever the Indians win a playoff game, I use the same water to keep the wins coming.”

Dave’s interesting superstition did bring the Indians luck when we visited, as the Tribe took a two-games-to-none lead over the Mariners in the series. However, the M’s came back to win. We’re not sure if Dave’s girlfriend made him change the dirty water, or if the dirty water trick only works when the Indians are playing at home. We do know that ever since then, we don’t eat boiled hot dogs handed to us from strangers or even friends without first asking how recently their water was changed.

DETROIT TIGERS,

DETROIT TIGERS,COMERICA PARK

A Motor City Miracle

D

ETROIT

, M

ICHIGAN

170 MILES TO CLEVELAND

230 MILES (370 KILOMETERS) TO TORONTO

265 MILES TO CINCINNATI

285 MILES TO CHICAGO

A

once-proud and highly successful franchise, Detroit hit rock bottom in the 1990s. The Tigers were perpetual cellar dwellers, their once-glorious Tiger Stadium had fallen into disrepair, and even many loyal fans cringed at the thought of visiting the crime-addled streets of Tiger Town. Something had to be done.

Now, you know we’re normally purists and urge the restoration of the classic era ballparks whenever possible. And you may have noticed that we usually praise those teams that have revitalized their dilapidated urban neighborhoods with new ballpark projects. But in this case, we think Tigers ownership made the right call. While it may have been feasible to renovate the old yard or build a new one somewhere in its desolate vicinity, our visits to Tiger Stadium had convinced even us that it was time for Major League Baseball to pull up stakes and head for greener pastures elsewhere in the city. The team wisely opted to make the new ballpark part of a downtown entertainment district, with the other pro sports venues and theatres and restaurants right nearby.

Beautiful Comerica Park opened on April 11, 2000, with the Tigers beating the Mariners 5-2 on a balmy April day. Actually, it was 34 degrees. But it could have been worse; the day before it had snowed in Detroit.

At first Comerica did little to improve the team’s performance, but as a renewed interest in the Tigers mounted, attendance surged, and the men and women in the front office put their noses to the proverbial grindstone. It all culminated, of course, in 2006 when the Tigers snapped a string of twelve straight losing campaigns by going 95-67. That record was good enough for a second-place finish in the AL Central and a claim to the AL Wild Card. The Tigers went on to shock the heavily favored Yankees in the AL Division Series and then swept the A’s in the ALCS before succumbing to the Cardinals in the World Series. It was a pretty impressive run from a team that had won just seventy-one games the year before and had set the AL record for most losses in a season just a few years earlier when it went 43-119 in 2003.

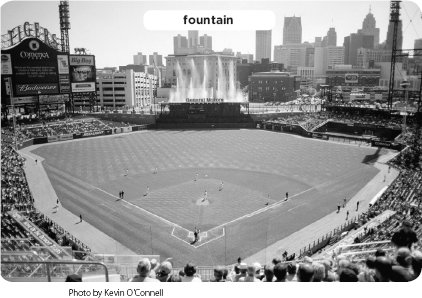

Little Caesar’s pizza maven Mike Ilitch, who has owned the Tigers since 1992 and the NHL’s Red Wings since 1982, played a leading role in Comerica’s design. And though amusement park rides, liquid fireworks, and other novelties sometimes make the stadium seem more like an ideal setting for a carnival than for a baseball game, Comerica presents a warm, festive environment for true fans too. Once you get past the kiddie rides and reach your seats, it feels almost as if you’re at an old-time park. The dirt path from the pitcher’s mound to home plate is a very nice touch as is the steel and brick construction, the center-field ivy, and the outfield view of downtown.

The 50-percent-privately-funded stadium project cost $350 million to complete, or to put it another way, Comerica cost more than a thousand times what it took to build Tiger Stadium. That venerable yard debuted as Navin Field in 1912 after having been erected for $300,000. Now that’s what we call stadium inflation!

Kevin:

But did they have a Ferris Wheel at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull?

Josh:

Well, no.

Kevin:

That must explain the difference.

Comerica’s main entrance is one of the most distinctive in baseball. For our money, it ranks right up there with the colorful plaza in Atlanta and old-timey rotunda in Queens. In Motown eighty-foot-high baseball bats flank the front gate and a massive sculpture of a tiger lurks in the courtyard. On the front of the ballpark itself, drain spouts sculpted to look like enormous tiger heads chomp down on oversized baseballs. Clearly, these are not the happy-go-lucky cartoon Tigers you knew and loved in the 1980s. These angry cats announce to all comers that their bite is as bad as their growl and they’re ready to tear the opposition to pieces.

Inside the park, the batters’ eye in center is made of mesh and covered with ivy, in an obvious tip of the cap to Wrigley Field. Up on top there’s a Chrysler logo. While usually we don’t like Corporate America making itself too prominent inside the park, in Detroit, this struck us as a nice touch. After all, this is Motown.

Kevin:

But there’s also a Toyota sign on the right-field fence.

Josh:

A sign of the times, my friend.

A walkway behind the ivy doubles as a misting tent on hot days, connecting right field and left, and allowing fans a peek—but just a peek—of the action between the vines. When a Detroit player hits a home run, liquid fireworks explode out of the vines in celebration. The water show is no match for Kauffman Stadium’s fountain, but it’s still a spectacle. If the Tigers don’t homer, don’t despair, we were treated to a postgame water show after the last out, even though the Tigers lost. But root for a hometown homer, because that way you’ll also get to see the eyes of the colorful tigers atop the scoreboard light up too.

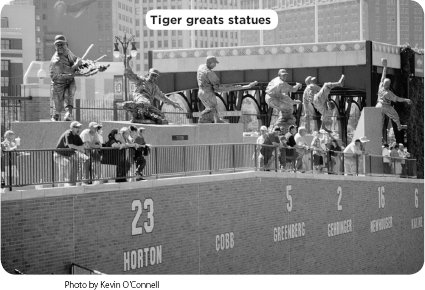

Realism collides with art on the left-field pavilion where statues depict several Tiger heroes. These include Charlie Gehringer, Hank Greenberg, Ty Cobb, Willie Horton, Al Kaline, and Hal Newhouser. A sculpture of Hall-of-Fame Tigers broadcaster Ernie Harwell, meanwhile, appears just outside the entrance to the park. The latter gentleman was so beloved in Detroit that upon his death in 2010 his body was laid in repose at Comerica Park. More than ten thousand mourners turned out to pay their last respects to the man who was the Voice of the Tigers for more than four decades.

As for the large metallic statues of the players, they are not meant to appear entirely true to life. The movement of one player’s bat whipping through the strike zone is simulated by a long blur of batlike steel. Another depicts three balls coming off a bat, and another shows turf flying in the air as a player runs. These fine works were sculpted by the husband-wife team of Omri Amrany and Julie Rotblatt-Amrany, the same Illinois artists who created the Michael Jordan statue outside Chicago’s United Center.

Kevin:

It’s always been a dream of mine to be statue-ized outside Safeco Field.

Josh:

That’s a little disturbing.

Kevin:

Just sayin’, it would be pretty cool.

Josh:

I don’t think they do that for guidebook writers.

The Detroit Tigers joined the American League as a founding member in 1901. But the franchise actually existed before the Junior Circuit did. The early Tigers were in Ban Johnson’s Western League, which evolved into the AL, and played on “the Corner,” a Detroit hardball hotbed since the early 1890s. Bennett Park stood at the intersection of Michigan and Trumbull, with elm and oak trees in-play in the outfield. The trees, which predated the American Revolution, were removed in 1900 as the Tigers prepared to join the Majors.

Tiger Stadium was originally called Navin Field to honor team president Frank Navin. It opened on April 20, 1912, the same day as Fenway Park in Boston. The Tigers capped the historic day by downing the Indians, 6-5. Like many other parks of its era, Tiger Stadium was constructed to fit into an actual city block, giving the field its quirks organically, and not as a matter of design. The distance to straightaway center field originally measured 467 feet. While the 125-foot-high center-field flagpole was technically on the field, it didn’t come into play often. In 1938 the center-field fence was brought in to 440 feet, where it would remain.

Milestone moments at Tiger Stadium included Ty Cobb’s three thousandth hit in 1921, Eddie Collins’s three thousandth in 1925, and Babe Ruth’s seven hundredth homer in 1934. Ruth’s blast cleared the right-field roof and left the yard entirely. The only All-Star Game won by the AL between 1962 and 1983 was played at Tiger Stadium

in 1971. A mammoth third-inning clout by Reggie Jackson struck a light tower above the right-center-field roof, propelling the Juniors to a 6-4 victory.

While twenty-three home runs cleared Tiger Stadium’s right-field roof, only four carried over the more distant left-field roof. The culprits: Harmon Killebrew (1962), Frank Howard (1968), Cecil Fielder (1990), and Mark McGwire (1997).

Kevin:

No light weights in that group.

Josh:

A pretty fair list of sluggers, indeed.

On September 27, 1999, Harwell delivered a touching eulogy for the ballpark before a sellout crowd shortly after the Tigers beat the Royals 8-2 in the finale. Then, with the assistance of a police motorcade and several Tigers players, home plate was driven one mile to Comerica’s construction site.

From the start, the new park “played big,” yielding homers sparingly and offering a great many triples. In 2005, the Tigers tinkered with the outfield configuration to bring in the fence in left-center from 395 feet to 370, and in center from 435 feet to 420. The move facilitated a relocation of the bullpens from right field to left-field home run territory. Even in the years since, Comerica has maintained its reputation as a pitcher’s park. But it’s not the hitter’s graveyard it once was.

The highlights of the ballpark’s first decade included playing host to the 2005 All-Star Game. On that July day, Al Kaline and Willie Horton threw out the ceremonial first pitches, and then the AL jumped out to a 7-0 lead thanks to homers by Miguel Tejada and Mark Teixeira, and a two-run single by Ichiro. The AL held on for a 7-5 win. Six years later, Comerica was the site of Jim Thome’s 599th and 600th home runs, which he hit on the night of August 15, 2011. Both long balls were of the opposite field variety, flying over the left-field fence, and they came in successive innings. In the sixth inning, the Twins’ designated hitter took Tigers’ starter Rick Porcello deep. Then, in the seventh, he became the eighth Major Leaguer to join the six-hundred-homer club with a three-run clout against reliever Daniel Schlereth.

Trivia Timeout

Chrysler:

Which Tiger holds the record for being the youngest batting champ in Major League history?

Chevy:

The famous headline “We Win!” appeared in the

Detroit Free Press

in what year?

Ford:

Name the three Tiger pitchers who have won the AL MVP award. (Hint: One won it more than once. Another won it after eclipsing the thirty-win mark. And one was a reliever.)

Look for the answers in the text.

Speaking of the Twins, they finished ahead of the Tigers in the AL Central standings by just a single game in 2006. But that didn’t stop the Tigers from advancing all the way to the World Series. As the AL Wild Card team, Detroit beat the Yankees three games to one in the Division Series and even got the chance to celebrate the clincher on the Comerica lawn. Then they moved on to face the A’s in the AL Championship Series. And not only did the Tigers win, but they registered a decisive series sweep, which they completed in the most dramatic fashion imaginable. Magglio Ordonez sealed the deal with a three-run walk-off homer in the bottom of the ninth to send the 42,967 fans at Comerica into a frenzy of delight. But in the October Classic the Tigers came up a little bit short. They and the NL champion Cardinals split the first two games, which were played in Detroit. Then the Tigers’ bats went dormant and their pitchers, oddly enough, started committing errors left and right. Tiger hurlers were charged with five miscues in the five-game series that sent them home to ruminate over what might have been. That 2006 season was an important one for Detroit, though, as it reestablished the Tigers as

a perennial force in the AL Central. The Tigers returned to the playoffs in 2011, but lost to the Rangers in a six-game ALCS. We suspect the Tigers will have plenty more opportunities to taste October champagne in the years ahead and when they do, no doubt beautiful Comerica Park will shine for the entire baseball world to see.