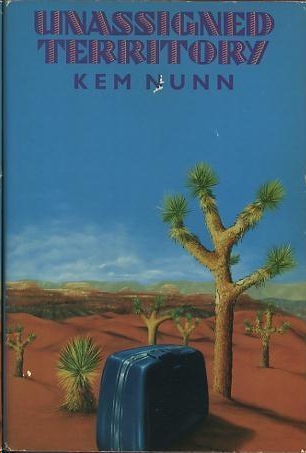

Unassigned Territory

Read Unassigned Territory Online

Authors: Kem Nunn

Tags: #Dark, #Gothic, #Fantasy, #Bram Stoker Award, #Mystery, #Western, #Religious

For Kathryn

I would like to thank Kimberly Kellington and Wayne Wilson, whose lyrics have managed to find their way into this text, and, especially, Robert Frizz Fuller, certainly, as Kerouac once said of Cassidy: an expert in subjects not yet identified, and without whose music the world would clearly be poorer.

When I was driving through El Paso

That’s when my car ran out of gaso

Robert Frizz Fuller/R.F.F.

Texas Tango

O

badiah Wheeler returned the receiver to its cradle and exhaled. He took one half of the small yellow tablet Bug House had dissected for him from the coffee table and popped it into his mouth, washed it down with a shot of Old Quaker, and followed that with a long pull from a can of Colt 45. Something to steady the nerves.

“So what now?” Bug House wanted to know.

“We wait.”

“They asked you enough questions.”

“Tell me. I think they’re checking your card.”

Bug House retrieved his credit card and driver’s license from the floor near Obadiah’s foot. “They think I’m you,” he said.

Obadiah nodded. Bug House seemed to find this amusing. Obadiah took another swallow of the Quaker and closed his eyes against the burn. “You think that was enough?” he asked, nodding toward the remainder of the tablet.

Bug House nodded. “You don’t want to sleep through it all, do you?” Obadiah thought this over; the prospect was not unattractive. He watched Bug House remove his glasses, pull a handkerchief from his pants, and wipe his brow. The flesh of Bug House’s face looked pink and damp. Bug House was not a well man.

When the phone rang it was much louder than Obadiah had expected and he jumped at the sound of it. He took one more swallow of the malt liquor and picked up the receiver. It was a woman this time. The woman was certainly less businesslike than the man he had spoken to earlier. “Hello, Richard,” the woman said. “Hello,” Obadiah answered, hoping to sound cool. The woman’s voice was soft and warm, like a wind out of the desert—the kind of voice he had expected in the beginning, he supposed. She made him repeat some of what he’d said to the man so that he guessed she was checking his story, but somehow the quality of her voice made it so he didn’t mind. “You’re a veteran?” she asked.

“Yes.”

“Disabled?”

“A back injury.” It was what Bug House had told him to say. “It’s better that way,” he had said. “Women don’t like it if you tell them you’re a lunatic.”

“And what kind of girl would you like, Richard?” There were young girls, older girls, black girls, and white girls, and oriental girls. Obadiah placed an order for something in white, young but not too young. Faced with such a decision he felt that he should be more specific in some exotic way—black and nothing short of six feet. But his imagination seemed to fail and he found himself sweating in the heat of the room, his own hopelessly square voice reverberating in his ears. A twelve-year-old oriental, perhaps, but he was too late and the woman was talking to him once again. “Well, I’m sure that you will be pleased, Richard,” and something in her voice made him feel that he had been right after all. “All our girls are very loving and warm,” the woman added. “They wear high heels and nylons.” Obadiah, not sure about how to respond, said nothing. “A girl will call you shortly, for directions. Good night, Richard.”

Obadiah said good night and gave the thumbs-up sign to Bug House, who had begun to fluff cushions on the small sofa, cushions Obadiah was certain had not been fluffed in many years. The room filled with dust. Obadiah stood up, swaying slightly, and walked to the window. He stared into the dead end of Thomas Street below him, watching an Olympia sign flicker in the window of Heart’s lounge. He looked north, through the red and white hoops of the neon billiard balls above Kempner’s, toward that place where an emaciated neon greyhound ran in the night, electric-blue legs stretched out before the blackness of invisible mountains, and a familiar loneliness tore at his heart.

Somewhere in the darkness behind him the phone was ringing once more. When he answered, there was another woman on the line. But the magic was gone. It was clearly a voice in which the breath of the desert did not live. “Where you at?” the voice wanted to know. Obadiah was some time in replying. The room seemed to be melting slowly around him—yellow icing running in the night. “The Pomona Hotel?” His words came back to him in the form of a question, followed by silence and a faint mechanical hum. “Ten minutes,” the voice said.

Once again Obadiah replaced the receiver, gave it another one, two, with the Quaker and Colt 45. Bug House stood sweating before him, dressed in a filthy pair of tan cords, a yellow and white baseball shirt. The shirt did not fit well and allowed Bug House’s stomach to hang out above his beltline. Obadiah himself was dressed in a pair of gray slacks, a pale blue dress shirt, and dark blazer. His mother had picked the clothes out for him at a fairly expensive men’s store. He’d worn a tie as well, a wide blue-and-burgundy affair that was now mashed into the side pocket of the blazer. He was dressed this way because he had just come from conducting a class in public speaking. The class lasted an hour. Each week there were five speakers and each speaker presented a talk on a biblical subject. It was Obadiah’s job to assign the subjects, then to critique the presentations. There were about a hundred people enrolled—what amounted to most of the congregation. The younger children often needed help in preparing their assignments, as did a few of the black brothers who did not read well. On this particular night, Obadiah had actually prepared all five of the presentations himself. He tilted his head back on the couch and fingered the tie in his pocket—a nervous gesture Bug House apparently seized upon as a subtle hint directed toward his own appearance, for he turned abruptly to regard himself in a small rectangular mirror hung at an absurd angle from one wall. “Guess I could change,” he said, moving away and speaking in a voice which seemed louder than necessary.

Obadiah, his eyes closed, could hear him a moment later at the closet, banging doors and rattling hangers. Bug House had names for all of his outfits. “What will it be?” he asked. “Doc Potty? G.I. Joe?” He settled on the Pomona Kimono—a silken black affair with large red flowers. “The casual look,” he said, standing near the foot of the bed and pulling the foul thing over his head. “But what the hell? She’s a whore, right?”

Obadiah was suddenly finding it difficult to speak. He had been pouring malt liquor on top of bourbon at a frightening pace. And somewhere in there was Bug House’s pill—perhaps accounting for the strange numbness now entering his face. He pulled himself to his feet and returned to the window. It occurred to him that he was at least as insane as Bug House—government-certified or not. Had this really been his idea? It was Bug House’s birthday; he could remember that much. Bug House’s birthday. Bug House’s card. Bug House’s name. He had been Bug House. But it had been his idea—there was no escaping it. Bug House had said that if Obadiah called he would foot the bill; they would put it on his card. But Bug House had not wanted to call himself—bugged lines, CIA involvement, unforeseeable complications resulting perhaps in case reviews, disability reductions—who knows? In short, Bug House had been afraid. Now Obadiah found that he was afraid as well. He did not know why, or of what, only that fear was sweeping over him in hot waves. “Guess they wouldn’t like it if they knew you were whoring around,” he heard his friend say. “What would they do? Kick you out? Take away your 4-D?” He could hear Bug House chortling to himself in a wicked fashion after each question and was forced to consider the answers against a background of laughter faintly demonic.

A 4-D was the classification given by the government to fulltime ministers. Obadiah was the owner of one. In order to maintain the status it was necessary to commit one hundred hours a month to the execution of ministerial duties. Twelve hundred hours a year. The class Obadiah had just come from counted as one of his duties. The month, however, was two-thirds gone and he was behind in his time. Failure to make the required number of hours for several months in a row could result in a loss of ministerial status. He looked into the blackness beyond the glass, at his own ghostlike reflection hung there above a dark street. The glass was old and rippled with time, giving back an indistinct reflection from which his features seemed to have fled, much, he suspected, like rats from a ship. He considered what was left—the bright patch of yellow hair, the brilliant sliver of an attempted mustache. He did not suppose ministerial activities could be stretched to include whoremongering. He found the prospect of losing the deferment a terrifying one and when he thought of it now, ugly alternatives seemed to rise before him like black, mutant shapes. Canada. Prison. One could, of course, go in. Bug House had gone in. He had left as Richard and come home as Bug House, home to full disability and a seedy room in the Pomona Hotel.

It was the fear of just such alternatives which had inspired Obadiah to agree to spend the next several days in unassigned territory—a last-ditch effort to salvage the month. The fact that the trip—an excursion into the desert with a group from his congregation—was to begin within the next twelve hours did, however, manage to lend a certain urgency to the insanity of the moment.

“Can’t lose that 4-D,” Bug House piped from what passed as a kitchen—a soiled bit of linoleum flooring at the far end of the room. “Christ no. There’s guys that would kill for one of those things.”

Bug House had by now moved to the edge of the carpet where he stood brandishing a pair of ridiculous-looking candle holders. The devices were shaped like the heads of Tiki gods commonly associated with the South Seas. These particular gods were made of plastic. One was red, one brown. Lighted candles sprouted from holes in the tops of their heads. “Atmosphere,” Bug House said. He tripped the room’s single overhead light with his elbow and the candlelight leaped to take its place.

“Minister claims pussy among duties,” Obadiah said. It sometimes pleased him to think of himself as the subject of headlines, particularly when drunk. He wondered why he was such a wiseass. Perhaps he was only confused.

Bug House had come close enough for Obadiah to take note of the rather intense scowl knotting his friend’s brow, of a look which might have passed for terror in his small, cubelike eyes. “I’m gonna make her sit on my face,” Bug House said. “I want a whore to sit on my face.”

“Sick,” Obadiah said. “The man’s sick.”

Bug House was still holding the candles and the shadows cast by their flickering light combined with the black silk and red flowers of the Pomona Kimono to produce what Obadiah found a most unpleasant effect—as if Bug House were a kind of priest in the middle of something you didn’t really want to know about. When he laughed the candles jiggled, lighting his face from the underside in a hideous fashion. Obadiah looked away. The laughter had a hollow machinelike ring to it and reminded Obadiah of the mechanical fat woman’s laughter he had once heard at a county fair. It was odd, he thought, that things had worked out as they had. In a world less twisted it might have been Obadiah’s place to point the way for poor Bug House, show him the light, as it were. As it was, he felt himself a partner in sickness, a sharer of darkness. He believed you were responsible for what you saw. It had come to him one afternoon while conducting a Bible study, discussing chapter nine of a book entitled

The Way of Truth.

The chapter was entitled “Why Does God Permit Wickedness?” and it had occurred to him that if this insight applied to God as well, the world was somehow a more difficult place to make sense of. He had kept the idea from his student, a tiny, humpbacked old man he was attempting to rescue from the Church of Christ, and continued as if nothing had happened.

Still, he had not begun cynically and it had not always been something like the fear of a lost deferment which had moved his faith to works. It was, after all, a path to which he had been bred. It had begun years ago on a clear winter day when a young housewife answered a knock on the door. She met a pair of attractive young women, not unlike herself. They talked about the last days and life on a paradise earth. The housewife had always, in a vague sort of way, expected to go to heaven—this when she thought of it at all. The women told her that wasn’t how it worked. They left literature. Later they returned to offer a free home Bible study. The woman accepted. Much to her husband’s chagrin. Who soon took to spending a great deal of his time at the local library. Though not a scholar, he intended to prove the Bible students full of shit. The plan backfired when he began to discover things he had not counted on—that Christ had in fact died upon a stake, that the origin of the cross as a religious symbol could be traced back to the god Tammuz and the ancient city of Babylon. He explored the intricacies of what this meant in the symbolic terms of the Revelation. He saw a great world empire of false religion, a shared collection of doctrine and symbol linked by a common origin. He came to understand that these bogus institutions claiming to represent God had, in fact, entered into adulterous relationships with the Kings of the earth, that though they made many prayers, it was like the man had said, their hands were full of blood. He was much impressed by Paul’s argument that it was, in his day, still possible to enter into the day of God’s rest—the suggestion being that the seventh day upon which God rested was still in progress, which in turn suggested that one need not consider the six days of creation as literal days but rather as creative cycles of indeterminate length. To make a long story short, the man and his wife were baptized. When their only son was born they gave him the name of a Hebrew prophet and all the answers a man could hope for.