Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption (56 page)

Read Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption Online

Authors: Laura Hillenbrand

Tags: #Autobiography.Historical Figures, #History, #Biography, #Non-Fiction, #War, #Adult

Graham’s weight was dropping, and dark semicircles shadowed his eyes. At times he felt that if he stopped moving, his legs would buckle, so he took to pacing his pulpit to keep himself from keeling over. Once, someone brought a baby to him, and he asked whose child she was. He’d been away from home for so long that he didn’t recognize his own daughter. He longed to end the campaign, but the success of it made him sure that Providence had other wishes.

When Louie and Cynthia entered the tent, Louie refused to go farther forward than the back rows. He sat down, sul en. He would wait out this sermon, go home, and be done with it.

The tent was hushed. From someplace outside came a high, beckoning sound. Louie had known that sound since his boyhood, when he’d lain awake beside Pete, yearning to escape. It was the whistle of a train.

——

When Graham appeared, Louie was surprised. He’d expected the sort of frothy, holy-rol ing charlatan that he’d seen preaching near Torrance when he was a boy. What he saw instead was a brisk, neatly groomed man two years younger than himself. Though he was nursing a sore throat and asked that his amplifier be turned up to save his voice, Graham showed no other sign of his fatigue. He asked his listeners to open their Bibles to the eighth chapter of John.

Jesus went unto the mount of Olives. And early in the morning he came again into the temple, and al the people came unto him; and he sat down, and taught them. And the scribes and Pharisees brought unto him a woman taken in adultery; and when they had set her in the midst, They say unto him, Master, this woman was taken in adultery, in the very act. Now Moses in the law commanded us, that such should be stoned: but what sayest thou? This they said, tempting him, that they might have to accuse him. But Jesus stooped down, and with his finger wrote on the ground, as though he heard them not. So when they continued asking him, he lifted up himself, and said unto them, He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her. And again he stooped down, and wrote on the ground. And they which heard it, being convicted by their own conscience, went out one by one, beginning at the eldest, even unto the last: and Jesus was left alone, and the woman standing in the midst. When Jesus had lifted up himself, and saw no one but the woman, he said unto her, Woman, where are those thine accusers? hath no man condemned thee? She said, No man, Lord.

And Jesus said unto her, Neither do I condemn thee: go, and sin no more.*

Louie was suddenly wide awake. Describing Jesus rising from his knees after a night of prayer, Graham asked his listeners how long it had been since they’d prayed in earnest. Then he focused on Jesus bending down, his finger tracing words in the sand at the Pharisees’ feet, sending the men scattering in fear.

“What did they see Jesus write?” Graham asked. Inside himself, Louie felt something twisting.

“Darkness doesn’t hide the eyes of God,” Graham said. “God takes down your life from the time you were born to the time you die. And when you stand before God on the great judgment day, you’re going to say, ‘Lord I wasn’t such a bad fel ow,’ and they are going to pul down the screen and they are going to shoot the moving picture of your life from the cradle to the grave, and you are going to hear every thought that was going through your mind every minute of the day, every second of the minute, and you’re going to hear the words that you said. And your own words, and your own thoughts, and your own deeds, are going to condemn you as you stand before God on that day. And God is going to say, ‘Depart from me.’ ” *

Louie felt indignant rage flaring in him, a struck match. I am a good man, he thought. I am a good man.

Even as he had this thought, he felt the lie in it. He knew what he had become. Somewhere under his anger, there was a lurking, nameless uneasiness, the shudder of sharks rasping their backs along the bottom of the raft. There was a thought he must not think, a memory he must not see. With the urgency of a bolting animal, he wanted to run.

Graham looked out over his audience. “Here tonight, there’s a drowning man, a drowning woman, a drowning man, a drowning boy, a drowning girl that is out lost in the sea of life.” He told of hel and salvation, men saved and men lost, always coming back to the stooped figure drawing letters in the sand.

Louie grew more and more angry and more and more spooked.

“Every head bowed and every eye closed,” said Graham, offering a traditional invitation to repentance, a declaration of faith, and absolution. Louie grabbed Cynthia’s arm, stood up, and bul ed his way from the tent.

Somewhere in the city, a siren began a low wail. The sound, rising and fal ing slowly, carried through the tent, picked up by the microphone that was recording the sermon.

That night, Louie lay helpless as the belt whipped his head. The body that hunched over him was that of the Bird. The face was that of the devil.

——

Louie rose from his nightmares to find Cynthia there. Al morning Sunday, she tried to coax him into seeing Graham again. Louie, angry and threatened, refused. For several hours, Cynthia and Louie argued. Exhausted by her persistence, Louie final y agreed to go, with one caveat: When Graham said,

“Every head bowed, every eye closed,” they were leaving.

Under the tent that night, Graham spoke of how the world was in an age of war, an age defined by persecution and suffering. Why, Graham asked, is God silent while good men suffer? He began his answer by asking his audience to consider the evening sky. “If you look into the heavens tonight, on this beautiful California night, I see the stars and can see the footprints of God,” he said. “… I think to myself, my father, my heavenly father, hung them there with a flaming fingertip and holds them there with the power of his omnipotent hand, and he runs the whole universe, and he’s not too busy running the whole universe to count the hairs on my head and see a sparrow when it fal s, because God is interested in me … God spoke in creation.”*

Louie was winding tight. He remembered the day when he and Phil, slowly dying on the raft, had slid into the doldrums. Above, the sky had been a swirl of light; below, the stil ed ocean had mirrored the sky, its clarity broken only by a leaping fish. Awed to silence, forgetting his thirst and his hunger, forgetting that he was dying, Louie had known only gratitude. That day, he had believed that what lay around them was the work of infinitely broad, benevolent hands, a gift of compassion. In the years since, that thought had been lost.

Graham went on. He spoke of God reaching into the world through miracles and the intangible blessings that give men the strength to out-last their sorrows. “God works miracles one after another,” he said. “… God says, ‘If you suffer, I’l give you the grace to go forward.’ ”

Louie found himself thinking of the moment at which he had woken in the sinking hul of Green Hornet, the wires that had trapped him a moment earlier now, inexplicably, gone. And he remembered the Japanese bomber swooping over the rafts, riddling them with bul ets, and yet not a single bul et had struck him, Phil, or Mac. He had fal en into unbearably cruel worlds, and yet he had borne them. When he turned these memories in his mind, the only explanation he could find was one in which the impossible was possible.

What God asks of men, said Graham, is faith. His invisibility is the truest test of that faith. To know who sees him, God makes himself unseen.

Louie shone with sweat. He felt accused, cornered, pressed by a frantic urge to flee. As Graham asked for heads to bow and eyes to close, Louie stood abruptly and rushed for the street, towing Cynthia behind him. “Nobody leaving,” said Graham. “You can leave while I’m preaching but not now.

Everybody is stil and quiet. Every head bowed, every eye closed.” He asked the faithful to come forward.

Louie pushed past the congregants in his row, charging for the exit. His mind was tumbling. He felt enraged, violent, on the edge of explosion. He wanted to hit someone.

As he reached the aisle, he stopped. Cynthia, the rows of bowed heads, the sawdust underfoot, the tent around him, al disappeared. A memory long beaten back, the memory from which he had run the evening before, was upon him.

Louie was on the raft. There was gentle Phil crumpled up before him, Mac’s breathing skeleton, endless ocean stretching away in every direction, the sun lying over them, the cunning bodies of the sharks, waiting, circling. He was a body on a raft, dying of thirst. He felt words whisper from his swol en lips.

It was a promise thrown at heaven, a promise he had not kept, a promise he had al owed himself to forget until just this instant: If you will save me, I will serve you forever. And then, standing under a circus tent on a clear night in downtown Los Angeles, Louie felt rain fal ing.

It was the last flashback he would ever have. Louie let go of Cynthia and turned toward Graham. He felt supremely alive. He began walking.

“This is it,” said Graham. “God has spoken to you. You come on.”

——

Cynthia kept her eyes on Louie al the way home. When they entered the apartment, Louie went straight to his cache of liquor. It was the time of night when the need usual y took hold of him, but for the first time in years, Louie had no desire to drink. He carried the bottles to the kitchen sink, opened them, and poured their contents into the drain. Then he hurried through the apartment, gathering packs of cigarettes, a secret stash of girlie magazines, everything that was part of his ruined years. He heaved it al down the trash chute.

In the morning, he woke feeling cleansed. For the first time in five years, the Bird hadn’t come into his dreams. The Bird would never come again.

Louie dug out the Bible that had been issued to him by the air corps and mailed home to his mother when he was believed dead. He walked to Barnsdal Park, where he and Cynthia had gone in better days, and where Cynthia had gone, alone, when he’d been on his benders. He found a spot under a tree, sat down, and began reading.

Resting in the shade and the stil ness, Louie felt profound peace. When he thought of his history, what resonated with him now was not al that he had suffered but the divine love that he believed had intervened to save him. He was not the worthless, broken, forsaken man that the Bird had striven to make of him. In a single, silent moment, his rage, his fear, his humiliation and helplessness, had fal en away. That morning, he believed, he was a new creation.

Softly, he wept.

* From the King James version.

* Excerpts taken from “The Only Sermon Jesus Ever Wrote,” sermon by Bil y Graham, © 1949 Bil y Graham Evangelistic Association. Used with permission. Al rights reserved. Author’s transcription from audio recording.

* Excerpts taken from “Why God Al ows Christians to Suffer and Why God Al ows Communism to Flourish,” sermon by Bil y Graham, © 1949 Bil y Graham Evangelistic Association. Used with permission. Al rights reserved. Author’s transcription from audio recording.

Thirty-nine

Daybreak

a

long,

level

road

toward Oa

complex

of

unadorned

buildings.

As

he

approached

the

archway

that

marked

the entrance to the complex, his whole body tingled. On the arch were painted the words SUGAMO PRISON, and beyond it waited Louie’s POW camp guards. At long last, Louie had returned to Japan.

In the year that had passed since he had walked into Bil y Graham’s tent, Louie had worked to keep a promise. He had begun a new life as a Christian speaker, tel ing his story al over America. The work brought him modest honoraria and offerings, enough to al ow him to pay his bil s and buy a $150 used DeSoto, final y replacing the car that he’d lost as loan col ateral. He had scraped together just enough money for a down payment on a house, but was stil so poor that Cissy’s crib was the house’s only furniture. Louie did the cooking on a single-coil hot plate, and he and Cynthia slept in sleeping bags next to the crib. They were barely getting by, but their connection to each other had been renewed and deepened. They were blissful together.

In the first years after the war, a journey back to Japan had been Louie’s obsession, the path to murdering the man who had ruined him. But thoughts of murder no longer had a home in him. He had come here not to avenge himself but to answer a question.

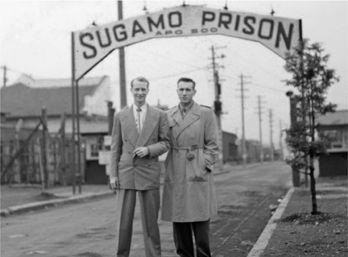

Louie (right) at Sugamo. Courtesy of Louis Zamperini

Louie had been told that al of the men who had tormented him had been arrested, convicted, and imprisoned here in Sugamo. He could speak about and think of his captors, even the Bird, without bitterness, but a question tapped at the back of his mind. If he should ever see them again, would the peace that he had found prove resilient? With trepidation, he had resolved to go to Sugamo to stand before these men.

On the evening before, Louie had written to Cynthia to tel her what he was about to do. He had asked her to pray for him.

——

The former guards, 850 of them, sat cross-legged on the floor of a large, bare common room. Standing at the front of the room, Louie looked out over the faces.