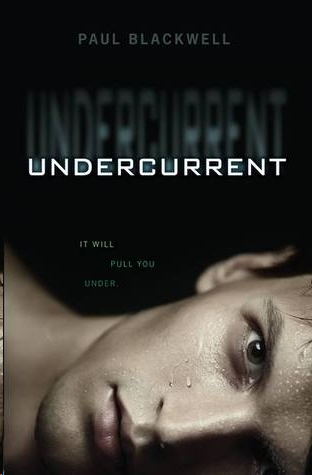

Undercurrent

Authors: Paul Blackwell

Tags: #Young Adult Fiction, #Horror, #Mysteries & Detective Stories, #Social Themes, #New Experience

F

OR MY PARENTS

, D & L

CONTENTS

A

hundred and twenty thousand gallons of water roar over Crystal Falls every second, it says on all the plaques and in all the pamphlets around town.

Which is almost two million glasses—or two thousand bathtubs or six full swimming pools—spilling every second, plunging eighty feet to boom against rocks and turn into mist, foaming and churning and swirling in a giant bowl before raging madly away downriver.

I would’ve never guessed I’d go along for the ride. But still, I didn’t scream. I didn’t scream or struggle or do anything like that. I just crossed my arms and went over like I was already in a coffin.

It’s black where I am. All night sky and no stars.

And silent. Or at least it was. Because sounds are starting to reach me now: footsteps. Hushed voices. A little beep that never stops. And things are becoming less black, more of a dark red, like a pool of blood. For a moment I even see something—a room, whiter than white—before a light blinds me. Then it’s back to the red again.

I still don’t know where I am.

“Cal, can you hear us? Make a noise if you can hear us. . . .”

My father’s voice startles me, but I can’t move a muscle to show it. I feel a hand drawn over my forehead. It’s heavy and warm. Fingers brush back my hair. I can hear my mother nearby, crying.

“Just make a noise, Cal,” my father begs. “Anything . . .”

Okay, sure. I’ll grunt or something, to let them know I’m alive and listening. How hard can that be?

But it’s impossible. Because nothing happens. My throat, my tongue, my lips—they’re all frozen.

I try moving an arm and, failing that, waggling a finger. But my body feels like it’s made of stone. The deepest breath I can take is barely enough to make my lungs inflate.

No—no—this is not good. . . .

My panic explodes as I feel hands caress my limbs, my cheek, my head. Christ, I’m paralyzed. I must have broken my back or smashed my head or something—and now I’m trapped in here, a vegetable. I want to scream now—I really want to scream.

Touches and kisses only make it worse. My head rings with shrieks. I pound imaginary little fists against the inside of my skull. I scream, I swear, I cry—but it’s all swallowed up by this horrible black hole inside me.

I know where I am now.

I am in hell.

Eventually I must pass out and start dreaming. First about our family’s life before Crystal Falls, of the fields and forests where my brother, Cole, and I used to run wild and the quiet river where we used to canoe. I miss those places a lot and dream about them often.

But then things change.

Suddenly the day turns dark, and I’m hanging from the swaying footbridge over the roaring falls. Clamped on the icy railing, my fingers are killing me. I can’t hold on much longer.

Losing my grip, I cry out:

“No!”

I wake up with what feels like a violent start, but my body still doesn’t respond. I can hear the beeps again. They must be coming from a machine monitoring my life signs. Which must mean I’m in the hospital.

Yeah, I’m sure of it now. The reek of disinfectant, the bleached sheets, and the weird odor that reminds me of thunderstorms. I can’t mistake them all.

I’ve always had a powerful sense of smell. It’s in the family genes, my father says. And he should know, having built a whole career out of his, sniffing beers and spirits for breweries and distilleries. The Harris nose is a gift, he once told me, like an ear for music or a photographer’s eye.

Well, it seems more like a curse to me. For starters, if it weren’t for this supposed gift, we would never have come to this stupid town. And because of my own superior sense, I can’t stand hospitals—and now it looks like I’m stuck in one forever.

“You can get through this, Cal,” my dad whispers from somewhere nearby. “You’re such a tough kid—this is nothing to you.”

Huh? Okay, now he’s confusing his sons. Because I’m not the tough one, that’s for sure. It’s Cole’s favorite excuse for whaling on me, in fact—that I’m such a whiny little wimp:

That’s why God made big brothers,

he’d explain, while flicking my ear or punching me in the biceps,

to toughen up pansies like you. . . .

My heart sinks as my mother starts crying. I know this particular sound very well. And I know, if there’s anything she can’t bear, it’s false hope.

“Oh, Cal,” she sobs. “Oh, sweetie . . .”

I wish I could answer my parents and somehow let them know I’m still in here. Then a terrifying possibility hits me: What if they’re thinking of calling it quits? What if they’re thinking of pulling the plug on me?

But wait. There are probably tests that show I’m still in here. Brain scans. I wonder what my life looks like now—some red, an area of green, a few bright blue blobs on some computer monitor?

Yeah, I’m sure they must be able to see me thinking, dreaming. They must know that my brain is not completely dead.

What I don’t get is why they keep calling me Cal. It’s something they stopped doing years ago, in order to clear up any confusion when shouting across the house. Even before Crystal Falls, my parents had switched to calling me Callum—as had everyone else except Cole, who’d only use my full name to show he thinks I’m being a tool.

Speaking of Cole, I haven’t heard him so far. Where is he? Having broken enough bones in his life, he hates hospitals, too, I know; but I would’ve expected him to come visit his comatose brother. What the hell?

To the sound of my mother softly crying, I must fall asleep. Because the next thing I know, I’m awakened by a stab of pain in my hand. Surfacing to the red again, I finally figure it out: I’m seeing the insides of my eyelids.

The beeps are back, but the sobbing has stopped.

For a moment everything else is quiet. But then I hear the sound of tape being torn off a roll. There is more pain on the back of my hand as the tape is then stuck on me. It’s holding a needle down, I assume—I must be on some sort of IV drip. I can smell the perfume coming off the mysterious person, who must be a nurse. Who else would stab people with needles? Her perfume is really strong, though, and reminds me of toilet cleaner.

There’s a bang—something thrown in the garbage, I think. Then the squeak of little wheels. A tray?

There is no more noise for a moment. Nothing but the beeps. I cling to their sound, not wanting to slip back into the blackness. I’m so tired, though.

I suddenly feel hot breath in my ear.

“I hope you never wake up,” a voice whispers.

The woman’s words horrify me—my body feels like it’s been shot through with an electric current. Then the breath is gone, the sickly perfume wafting after it.

I hear soft-soled shoes walking away.

My eyes open. The room seems painfully bright, though there’s only a single lamp on.

Who cares? At least I can see now. Which means I’m back—I’m back!

But can I move? I’m not sure at first. When I finally become used to the light, I try turning my head.

My head feels as heavy as a sack of bowling balls. But it’s moving, my neck creaking with the effort.

Two worn old armchairs come into sight. Orange ones. My mother’s cardigan is draped across the back of one, so she must be around. Maybe she went for a coffee or to the washroom or something. I just have to wait for her. And keep my eyes open.

As the room comes into better focus, I can see a window above the chairs. The curtains are open a little, and it’s nighttime, with parked cars gleaming in the streetlights. A minivan pulls in. Maybe it’s Dad—he has a van. But no. His van is blue, and this one is silver.

I’m getting frustrated. It’s becoming harder and harder to keep my eyes open. My blood feels like maple syrup. But I’m able to move my fingers now, and my arms a little. I can even see my toes wiggling under the sheets.

Everything feels like it’s working. I’m definitely not paralyzed. If I wasn’t so tired, I would be smiling from ear to ear now. This must be a good sign, I tell myself, before my entire head is swallowed up by a yawn.

Man, I wish someone would come into the room! Wait, there must be a button somewhere I can push to get somebody’s attention. They always have them by hospital beds. But then I remember the nurse with the perfume, and I’m afraid she’s the one who will come running.

No. I just have to wait for Mom. But I can’t hold out any longer—I fall asleep.

When I open my eyes again, I feel very groggy. I don’t know how long I’ve been out. I can still move, but it takes an incredible effort just to turn my head toward the orange chairs.

My mother is still not back.

That’s when I notice someone standing there, outside the window. It’s a guy in a green jacket with white leather sleeves, a sprinting crocodile embroidered on the chest. With the hood of a sweatshirt pulled up, most of the person’s face is in shadow. But still, there’s no mistaking the Harris nose, as distinctive as it is sensitive.

It has to be Cole.

What’s he doing standing out there? I want to call out, signal to him somehow, but I can’t. Instead I stare back blankly at him.

Behind me I hear the door swing open. The figure in the window slips from view like a ghost.

Someone’s coming into the room. I try to turn my head back, but I’m only able to move it halfway. Am I sedated or something? I can’t keep my eyes open a second longer. But I don’t go completely under, because I hear someone speak:

“Hello, Cal. Remember me?”

It’s not Mom, or even Dad, but it’s still a great voice to hear. It’s Bryce. I knew he would come to see me. Despite my exhaustion I feel a fluttering in my eyelids. They’re opening. I’m going to wake up for him, I know it.

Just then the pillow is pulled out from under my head. There’s a spark of pain as my head bounces off the mattress.

Ow! What’s he doing?

“This is for Neil. . . .”

I suddenly feel something press down over my face. And just then I remember how all that water felt, pouring over the falls onto me. It was like a mountain, pounding down, driving me under.

The pillow is nowhere near as heavy. But it doesn’t matter. I’m no more able to breathe than when I was at the bottom of the river, slammed against the rocks.

And I’m no more able to stop my best friend, Bryce, who is now grunting with the effort of smothering me.

Everything began going wrong when our family first pulled into

town.

WELCOME TO CRYSTAL FALLS—POPULATION 12,634

, the sign read.

The thing is, the number has never changed since. So unless they’d already added the four of us just before we arrived, the welcome is a lie. Or maybe it’s done on purpose, to let people know that if they weren’t born in Crystal Falls, they don’t really count.

Having lived here four years now, I find this makes a lot of sense.

Cole and I never wanted to move here. We liked where we lived already, at the edge of a city where we chased friends on bikes and waged war in the woods. There was even a river nearby that we canoed up and down, anywhere we wanted except the bulrushes, where we once got attacked by some swans we’d scared.

Then my father got a job offer. It was from Holden’s, an old family-owned whiskey distillery. Holden’s Own was one of the best products in the country, according to Dad.

The problem was, we’d have to move. Cole and I went nuts. There was no way—no way—we were going anywhere!

“Listen, guys, try to understand,” Dad told us. “Positions for master distillers don’t come up every day.” It was a huge opportunity, he explained, working for a company where art and craftsmanship still mattered. Was he supposed to just pass up the chance and keep slaving away at a big automated brewery?

Yes, we told him before the speech had finished coming out of his mouth.

Mom wasn’t happy either. “Crystal Falls?” she exclaimed. “I’ve never heard of the place.” Finding the town on a map, she saw how far east it was. “What about the holidays, Don? How will we see my sister and her family?”

“They can fly out and stay with us,” Dad said. “They have the money. Why are we always the ones driving out to see them, anyway? It’s their turn to make an effort.”

It all meant my father had already made up his mind. Despite our objections, he went and bought somewhere to live out in Crystal Falls. He then put a

FOR SALE

sign on the front lawn of the only home Cole and I had ever known, in the grass we’d played on since we were babies.

A couple weeks later, the

SOLD

sign went up. We moved shortly after that, once school was finished.

The new place was an old clapboard house set among some trees just off the road into town. The story was that a pastor used to live in it, until seventy years ago, when his church next door burned down. I would soon discover the grimy outline of a cross on my bedroom wall. Even three coats of paint couldn’t cover it up—which, even with a mirror hung over it, remains seriously creepy.

But that wasn’t the worst of it. Pulling up in the car, everyone could tell that Mom absolutely hated the house on sight.

“It’s really shady, Don,” she complained as we waited on the porch for the moving van to show up. “And old. I thought we decided on something nice and bright—a nice, new bungalow or something . . .”

Dad sighed, a dark look crossing his face. He assured us there wasn’t anything like that available. Plus this house was close to his work, which made a nice change from his old commute, which had kept him on the road two hours each day. That meant ten hours a week, five hundred hours a year, or so he loved reminding everyone.

“And as far as the shade goes, Liza, I’ll just cut down a few trees,” my father promised. “It’s no big deal,” he insisted.

Big deal or not, Dad never got around to it, and the trees have pushed farther in, scraping at the house in the wind. But then, Dad didn’t get around to a lot of things since coming to the house in Crystal Falls, which led to arguments with Mom. Even after he hired a guy to fix up a few things, the arguing didn’t stop. Not until Dad moved out.

Which was great. They moved the whole family across the country just to split up.

As far as Cole and I are concerned, the problem has never been the house—it’s the location. Most people live on the north side of the bridge by the falls, where the stores, the restaurants, and everything else of interest is located.

Meanwhile, down on the south side, where our house is, there’s pretty much nothing going on except for the campground and the old quarry. Oh, and the road out of town—which eventually leads back to where we used to live.

The joke of it all is that when Dad moved out, he ended up living on the north side. Okay, so that’s where the apartments are, but still, somehow it figures. He lives above a diner though, so his place always stinks like a fryer. Personally I don’t know how his supposedly refined sense of smell can stand it.

And if that isn’t bad enough, the apartment is tiny, with only a lumpy foldout couch for guests to sleep on. After just one sleepover, I knew that was enough. I don’t care how far I have to walk or if it’s raining butcher’s knives—I’m going home. I need my sleep.

It sucks, though, because Dad lives close to Bryce. And sometimes I get caught up in video games and end up staying late at Bryce’s house, so it would be handy to have somewhere to crash nearby instead of walking all the way back home in the dark.

Bryce—I don’t even know where to begin. I didn’t want anything to do with him at first, to be honest. It wasn’t personal. I just didn’t want to get chummy with someone who was a punching bag for Hunter Holden and Ricky Cho, who are now two of the school’s biggest football stars.

Wait, did I say

stars

? That’s a joke. The Crocodiles are what, second to last in the league now? Like I give a damn, ever since my brother was thrown off the team.

I still feel guilty about that, because it was kind of my fault. What happened was this: Since I was the new kid in Crystal Falls, people weren’t exactly lining up to be my friend. So rather than die of boredom, I started hanging out with Bryce anyway. He was a little weird, sure, but funny. And spoiled, which meant he had his own TV and a stack of video games.

But as expected, Hunter and Ricky soon started hassling me as well. Which was a little surprising, because they must have known I was Cole’s little brother, since we look enough alike. Cole, on the other hand, had wasted no time establishing his reputation at Crystal Falls. Before long he made quarterback and was tearing it up on the field. The Crocodiles became the best team in the league.

But who knows what was going on—maybe they were jealous of him. Some stranger shows up and takes the top slot on their football team? That’s gotta ruffle a few feathers.

Anyway, it’s not like I cared much about getting picked on. At least I had the guts to stick by a friend instead of running off like a coward. I might not be that tough, but I’m not a total wimp.

And so it went for a few years, with Bryce and me hanging out and taking crap. It was annoying but nothing I couldn’t handle—and definitely not something worth getting Cole involved in.

Then one day after getting shoved in the hall, Bryce went and lipped off to Hunter and Ricky. I can’t remember what he said—something about what steroids had done to their dicks, I think. But whatever it was must have hit close to home, because they went for him—hard. And of course nobody did anything to stop them. So I ended up jumping in and getting popped a couple of times, including one square in the eye.

Which sucked but was really no big deal. So long as you can still see, a black eye is cool, isn’t it?

Less cool was how impossible it was to hide the injury from Cole, though. Because besides him, no one is allowed to pound his brother—not even fellow Crocodiles.

That afternoon things got ugly. Even two on one, the juniors were no match for my brother, the bigger, tougher senior. It was a thing of beauty, I have to say, the way Cole laid them out in the parking lot. He flattened Ricky with one punch—

bam

, down—before throwing Hunter over his shoulder using a judo move he learned when he was ten.

Then Cole dropped on Hunter’s chest with both knees and began hammering his face in. That was scary. If he hadn’t been pulled off by teachers, I don’t know when he would have stopped—when his fists were broken, probably. I’d never seen him that mad—and I’d seen him really lose it before.

Everything was a big mess afterward. Because you just don’t screw around with the Holdens, not in Crystal Falls. Not only does their whiskey distillery provide a ton of jobs—our own father’s included—but they own like half the town. The best they could do with Hunter’s nose was make it stick back out again, with my parents footing the bill.

Cole got thrown off the football team just like that. I bet all it took was one phone call from Dad’s boss, Blake Holden—that rich prick probably wasted no time in reminding Coach Keller how he was building the brand-new bleacher seating and paying for the field’s upgraded PA system. Instead of getting cut the usual slack as an MVP, Cole suddenly got a lot of zeros on overdue assignments, which meant repeating his senior year.

Hunter was let off with a warning about playing rough with the younger kids. And then he waltzed straight into the vacant position of QB.

None of it was particularly surprising, because that’s how things are done around here. At least when the Holdens are involved.

Cole went totally ballistic again. After he trashed Coach Keller’s office, it was a miracle he was only suspended. Maybe the school was secretly ashamed about the raw deal he was getting and decided to give him a tiny break. There was no point in fighting it; we were worried enough that Dad might lose his job.

So Cole had no choice. He had to let it go.

Luckily, Dad and his bionic Harris nose aren’t easily replaced. And neither was Cole, for that matter. The Crocodiles began tanking in the standings big-time.

Heh-heh-heh.

Still, I felt awful. Cole loved playing football more than anything—and I had screwed it up for him. I should have known better—I should have covered things up somehow. But people saw what Hunter and Ricky did. Cole would have found out eventually.

Then again, I could have just stayed out of things in the first place. I could have let Bryce take the beating he’d pretty much asked for, being a smartass to a couple of gorillas. But I don’t know. Bryce is a friend—a good friend.

Or at least I thought he was. Until now.